Effects of alcohol on some biochemical parameters of alcoholics in nsukka, enugu state, nigeria

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Alcoholism2.2 Effects of Alcohol on the Body

2.3 Biochemical Parameters Affected by Alcohol

2.4 Risk Factors for Alcoholism

2.5 Behavioral and Social Impacts of Alcoholism

2.6 Psychological Effects of Alcoholism

2.7 Treatment and Interventions for Alcoholism

2.8 Global Perspectives on Alcoholism

2.9 Current Trends in Alcohol Research

2.10 Gaps in Existing Literature

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Design3.2 Population and Sampling Methods

3.3 Data Collection Techniques

3.4 Variables and Measurements

3.5 Data Analysis Methods

3.6 Ethical Considerations

3.7 Limitations of the Methodology

3.8 Validation of Research Instruments

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Overview of Research Findings4.2 Analysis of Biochemical Parameters in Alcoholics

4.3 Comparison with Control Group

4.4 Correlation Analysis

4.5 Discussion on Findings

4.6 Implications of Findings

4.7 Recommendations for Further Research

4.8 Practical Applications of Results

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Findings5.2 Conclusions

5.3 Contributions to Knowledge

5.4 Recommendations for Practice

5.5 Suggestions for Future Research

Thesis Abstract

This work was aimed at finding the effects of alcohol on some biochemical parameters. A total of one hundred and eighty (180) apparently healthy, non-hypertensive male alcoholics were used for the study. Forty (40) non-consumers of alcohol were used as control. The activity of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in the control was 10.50±2.00 IU/L while it was 16.50±1.50 IU/L; 17.50±2.00 IU/L and 18.31±2.00 IU/L in alcoholics who showed preference for palm wine, beer and distilled spirit respectively. Also, the activity of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in the control was 9.51±0.35 IU/L while it was 18.44±0.40 IU/L, 19.21±0.19 IU/L, 20.32±0.64 IU/L i n alcoholics who showed preference for palm wine, beer and distilled spirit respectively. The ALT and AST activities of alcoholic subjects who showed preference for distilled spirit was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than those who showed preference for palm wine and beer. The activities of alcoholics who showed preference for palm wine was the lowest. Furthermore, the serum total bilirubin concentration of the alcoholics was significantly higher (p < 0.05) compared with the control. The serum total bilirubin concentrations were 18.65±2.10 μmol/l, 19.40±1.50 μmol/l and 22.75±1.60 μmol/l for alcoholics who showed preference for palm wine, beer and distilled spirit respectively. The serum total bilirubin of the control was 8.30 ± 2.00 μmol/l. The alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity of the alcoholic subjects was significantly higher (p<0.05) compared with the control. The ALP activity of the control was 61.50 ± 30.00 IU/L while the ALP activity was 174.20±2.50 IU/L, 175.10±1.50 IU/L and 177.40±1.00 IU/L in the three categories of alcoholics who showed preference for palm wine, beer and distilled spirit respectively. Moreover, the urine total protein concentration of the alcoholics was significantly higher (p<0.05) compared with the control. Alcoholics who showed preference for distilled spirit had urine total protein of 153.96±0.43 mg/dl followed by alcoholics who showed preference for beer and palmwine who had urine total protein of 152.74±0.42 mg/dl and 151.34±0.60 mg/dl respectively. The urine total protein of the control was 56.40±0.40 mg/dl. Furthermore, the urine specific gravity, serum urea and creatinine of the alcoholics were significantly higher (p < 0.05) compared with the control. However, the plasma sodium, potassium and creatinine clearance of the alcoholics were significantly lower (p < 0.05) compared with the control. The body mass index (BMI) of the three groups of alcoholics fell within the range of 18.50 to 24.90. The blood pressure of both the alcoholic and control subjects were normal (below 140/90 mmHg). This work therefore shows that chronic alcohol use could induce both hepatic and renal dysfunctions in the alcoholics which manifested in form of adverse variations in some biochemical parameters of prognostic and diagnostic utility.

Thesis Overview

INTRODUCTION

Generally, alcohol designates a class of compounds that are hydroxyl derivatives of aliphatic hydrocarbons. However, in this study, the term alcohol used without additional qualifications refers specifically to ethanol. A variety of alcoholic beverages have been consumed by man in the continuing search for euphoria producing stimuli. Among some people, alcohol enjoys a high status as a social lubricant that relieves tension, gives self confidence to the inadequate, blurs the appreciation of uncomfortable realities and serves as an escape from environmental and emotional stress.

Alcohol has been loved and hated at different times by different people. Alcohol has been celebrated as healthful especially to the heart (red wine) and most pleasant to the taste buds; and then dismissed as “demon’s rum” and “devil in solution” depending on the prevalent view.

In spite of the apparent divergent and sometimes conflicting opinions about alcohol, the consensus shared by drinkers and non drinkers alike is that excessive and chronic consumption of alcohol is a disorder. Like any other chronic disorder, it develops insidiously but follows a predictable course. The first or pre-alcoholic symptomatic phase begins with the use of alcohol to relieve tensions. The second (or prodromal) phase is marked by a range of behaviours including preoccupation with alcohol, surreptitious drinking and loss of memory (Hock et al., 1992). In the third (or crucial) phase, the individual loses control over his drinking. This loss of control is the beginning of the disease process of addiction. The individual starts drinking early in the morning and stays up drinking till late in the night. Impairment in biochemical activities becomes manifest as the organs of the alcoholic begin to deteriorate. Other medical problems develop by the time the alcoholic gets into the final (chronic phase). Prolonged intoxications become the rule. Alcoholic psychosis develops, thinking is impaired, and fear and tremors become persistent (Klemin and Sherry, 1981). A previously responsible individual may be transformed into an inebriate – stereotype alcoholic.

Fear-instilling but thought- provoking terms such as the “coming epidemic”, a “miserable trap”, have been used to show concern for the potential hazard of widespread alcoholism.

In its 1978 revision of the international classification of diseases, the World Health Organization defined alcoholism as “a state, psychic and usually also physical, resulting from taking alcohol, characterised by behavioural and other responses that always include a compulsion to take alcohol on a continuous or periodic basis in order to experience its psychic effects and sometimes to avoid the discomfort of its absence; tolerance may or may not be present. This definition emphasized the compulsive nature of drinking, the psychological and physical effects, and dependence (“discomfort of its absence”) (WHO, 1978).

The kidney and liver could be particularly vulnerable to the chemical assault resulting from alcohol abuse because they receive high percentage of the total cardiac output. Also, the liver is pivotal in intermediary metabolism; so ingested alcohol must come in contact with the liver and kidney. Alcohol could produce many of its damaging effects by the formation of dangerous, highly reactive intermediates such as acetaldehyde which may lead to glutathione depletion, free radical generation, oxidative stress and cell dysfunction.

Alcohol dehydrogenase in the presence of a hydrogen acceptor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) oxidizes ethanol to acetaldehyde. This is the initial obligatory biochemical event in alcohol induced hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic effects. Thus, it is important to find out in quantitative terms the effects of different types of alcohol drinks on some principal biochemical parameters of diagnostic utility.

1.1.1 Chemistry of Alcohol

The term ‘alcohol’ refers to a class of compounds that are hydroxy (-OH) derivatives of aliphatic hydrocarbons. There are many common alcohols – methanol or wood alcohol, isopropyl alcohol, the antifreeze diethylene glycol, and glycerine. In this study however, when the term alcohol is used without additional qualification, ethyl alcohol, a liquid also known as ethanol, is referred to. Alcohol can be considered as being derived from the corresponding alkanes by replacing the hydrogen atoms with hydroxyl groups. The hydroxyl group is the functional group of alcohols as it is responsible for their characteristic chemical properties. Monohydric alcohols contain only one hydroxyl group in each molecule. Monohydric alcohols form a homologous series with the general molecular formula CnH2n+1OH.

All alcoholic beverages arise from the process of fermentation. Indeed, ethanol, the alcohol in beverages, is the quantitative end product of yeast glycolysis. In the presence of water, yeasts are able to convert the sugar (glucose) of plants into alcohol, as depicted by the following chemical reaction:

C6H12O62C2H5OH+2CO2 + Yeast

Glucose lAcohol Carbon dioxide

A wide variety of plants have proved to be useful substrates for the action of yeast, and this is reflected by the different types of beverages used throughout the world.

1.1.2 Alcohol Production

Beer is generally considered to be of two types, the ale types, brewed with Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the lager type, brewed with Saccharomyces carlsbergensis. The main ingredients of beer are malted barley, the source of fermentable carbohydrates, proteins, polypeptides, minerals, and hops the primary purpose of which is to impart bitterness and the hop characteristic, but which also have antimicrobial properties, yeast and water. The basic processes for the brewing of beer include:

Malting involves the mobilization and development of the enzymes formed during germination of the barley grain. The grain is permitted to germinate under controlled conditions of moisture and temperature, the starch/enzyme balance then being fixed by kilning at drying temperatures as high as 104oC

(b) Mashing

During mashing, ground malt is mixed (mashed) with hot water. This serves both to extract existing soluble compounds from the malt and to reactivate malt enzymes which complete the breakdown of starch and proteins.

(c) Wort boiling

Wort is drained from the mash tun into a copper and boiled to inactivate malt enzymes. In traditional brewing, hops are added at this stage, the humulones (α-acids) being extracted and chemically isomerized. The resulting iso-humulones have a greater solubility and contribute the characteristic bitter flavour to beer, while the ‘hop character’ i s derived from essential oils. In recent years, there has been a tendency to replace hop cones with various types of hop pellets, powders or extracts including pre-isomerized hop products which may be added after fermentation. Boiling serves two other functions: reducing the potential for microbiological problems by effectively sterilizing the wort and coagulation of proteins followed by their removal as ‘trub’. Inadequate coagulation may adversely affect the subsequent fermentation due to interference with yeast:substrate exchange processes (membrane blocking) and lead to poor quality beer.

(d) Fermentation

Fermentations are considered to be of two distinct types: the top fermentation used in production of ales, in which CO2 carries flocculated Sacch. cerevisiae to the surface of the fermenting vessel, and the bottom fermentation used in production of lagers, in which Sacch. carlsbergensis sediments to the bottom of the vessel. Differentiation on the basis of the behaviour of the yeast is, however, becoming less distinct with the increasing use of cylindro-conical fermenters and centrifuges.

- Maturation (Conditioning; Secondary fermentation)

Maturation may be considered to include all transformations between the end of primary fermentation and the final filtration of the beer. These include carbonation by fermentation of residual sugars, removal of excess yeast, adsorption of various non-volatiles onto the surface of the yeast and progressive change in aroma and flavour. During maturation, priming sugar may be added or amyloglucosidase used to hydrolyse dextrins.

- The Production of Palm Wine

There are two main sources of palmwine namely: raphia palm particularly Raphia vinifera and Raphia hookeri; and the oil palm: Elaeis guineensis. Palm wine is an alcoholic beverage produced from the fermenting palm sap. The part tapped is the male inflorescence of a standing oil palm tree. The fermentable sugars present in palm wine are glucose, sucrose, fructose, maltose, and raffinose. The yeast species – Saccharomyces spp are responsible mainly for the conversion of the sugars in palm sap into alcohol as well as oxidative fermentation of alcohol to acetic acid.

In the fermentation of natural palm wine, lactic acid bacteria, Lactobacillus plantarium, Leuconostoc mentseriodes and Pediococcus cerevisiae are also involved. All of them utilize meyerhof parnas pathway which results in the formation of alcohol as well as organic acids. The leuconostoc mesenteriode is a hetero-fermenter and ferments sugar to produce acetic acid., lactic acid, ethanol and carbondioxide. Lactobacillus plantarium is a homofermenter and ferments sugars to produce mainly lactic acid and small amount of alcohol and carbondioxide. Pediococcus cerevisiae is also a homo fermenter and produces the same metabolites as Lactobacillus plantarium. Thus, the bacterial flora of palm wine contribute significantly to the fermentation of sugars to alcohol and the alcoholic constituent of palm wine varies with the species of palm tree from which the wine was tapped.

1.1.2.3 Production of Distilled Spirit

Nature alone cannot produce spirits or hard liquor by the simple process of fermentation. Yeast will continue to carry out fermentation until the alcoholic content becomes high. The process of distillation then helps to produce beverages with higher concentration of alcohol in form of distilled spirit.

1.1.3 Absorption, Distribution and Metabolism of Alcohol

After its ingestion, alcohol is rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream from the stomach and small intestines. The rate of alcohol absorption can be delayed by the presence of food or milk in the stomach. It is a common observation that when several drinks are taken on an empty stomach, a far more rapid and profound effect is observed than when an equivalent amount of alcohol is taken when there is food in the stomach.

1.1.3.2 Distribution

Alcohol gains access to all the tissues and fluids of the body. The concentrations of alcohol in the brain rapidly approach those levels in the blood because of the very rich blood supply to the brain and other organs such as the liver and the kidney. This is of obvious significance, because alcohol-induced dysfunctions in several organs depend on the concentration and duration of exposure of the organs to alcohol.

Two major pathways of alcohol metabolism have been identified namely alcohol dehydrogenase pathway and microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (MEOS).

- Alcohol Dehydrogenase Pathway

The primary pathway for alcohol metabolism involves alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), a cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of alcohol to acetaldehyde. This enzyme is located mainly in the liver but small amounts are found in other organs such as the brain and stomach.

During conversion of ethanol by ADH to acetaldehyde, hydrogen ion is transferred from alcohol to the cofactor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to form NADH. As a net result, alcohol oxidation generates an excess of reducing equivalents in the liver, chiefly as NADH. The excess NADH production appears to contribute to the metabolic disorders that accompany chronic alcoholism and to both the lactic acidosis and hypoglycaemia that frequently accompany alcohol poisoning.

- Microsomal Ethanol Oxidizing System (MEOS)

This enzyme system, also known as the mixed function oxidase system, uses NADPH as a cofactor in the metabolism of ethanol and consists primarily of cytochrome P450 2E1, 4A2, and 3A4. At blood concentrations below 100mg/dl (22 mmol/l), the MEOS system, which has a relatively high Km for alcohol, contributes little to the metabolism of ethanol. However when large amounts of ethanol are consumed, the alcohol dehydrogenase system becomes saturated owing to depletion of the required cofactor, NAD+. As the concentration of ethanol increases above 100mg/dl, there is increased contribution from the MEO system, which does not rely on NAD+ as a cofactor.

During chronic alcohol consumption MEOS activity is induced. As a result, chronic alcohol consumption results in significant increases not only in ethanol metabolism but also in the clearance of other drugs eliminated by the cytochrome P450s that constitute the MEOS system, and in the generation of the toxic by-products of cytochrome P450 reactions (toxins, free radicals H2O2). Metabolism occurs mainly via the zinc–containing enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). Other enzyme systems, such as the microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (MEOS) or catalase system are capable of metabolising alcohol.

Oxidation of alcohol by ADH involves the transfer of hydrogen via nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), which is converted to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced (NADH). The result of this oxidation is the metabolite acetaldehyde. The subsequent oxidation of acetaldehyde by aldehyde dehydrogenase also involves the reduction of NAD. Acetaldehyde is metabolized to acetate and this is transformed in to acetyl coenzyme A, which is then oxidized by the citric acid cycle to carbon dioxide and water. The rate limiting step in this metabolic process is the oxidation of alcohol to acetaldehyde since acetaldehyde is metabolized faster than it is formed.

- Patterns of Alcohol Use and Abuse

Patterns of alcohol consumption may range from its occasional use to relieve emotional stress, to periodic “spree” drinking, to extreme cases where the alcoholic has little or no control over the amount of alcohol consumed. Chronic and excessive consumption of alcohol is a health and psycho-social disorder characterized by obsessive preoccupation with alcohol and loss of control over alcohol consumption such as to lead continuously to intoxication (Johansson et al., 2003). Chronic abuse of alcohol is typically associated with physical disability, social maladjustments, emotional and occupational impairments.

The hallmarks of excessive and chronic alcohol abuse are:

- Psychological dependence

- Physical dependence

- Tolerance (Martin et al., 2008).

Psychological dependence is typically characterized by intense and uncontrollable craving for alcohol. The alcoholics’ desire for alcohol is intense, obsessive and overwhelming. The alcoholics are deeply concerned about how daily activities interfere with drinking than how drinking negatively militate against the performance of daily activities. Family, relationships, friends, profession and business are relegated to subordinate roles with full joy. Alcohol consumption becomes the driving and motivating force (Johansson et al., 2003).

Excessive and chronic consumption of alcohol produces unequivocal physical dependence, with the intensity of the syndrome associated with withdrawal directly proportional to the level of intoxication and its duration. Excessive consumption of alcohol on chronic basis directly or indirectly adversely modifies the physical and mental health of the abuser. Intermediate levels of alcohol consumption produce withdrawal symptoms typified by tremors or “shakes”, anxiety, sleeplessness and gastrointestinal upset.

Delirium tremens is one of the potentially risky withdrawal symptoms experienced by chronic abusers, when physical dependence has set in. Alcoholics that have delirium tremens suffer from restlessness, tremors, weakness, nausea and anxiety few hours after the last drink. Generally, these effects experienced by alcoholics on momentary withdrawal from alcohol serve as an impetus driving them to initiate another drinking bout in order to feel ‘normal’ again; thus, potentiating the physical dependence. The tremors could be so severe that the alcoholic on resuming drinking finds it difficult to successfully navigate beer bottle or cup to his mouth yet he craves for more alcohol.

In the early stages of this withdrawal syndrome after the onset of physical dependence, the alcoholic is hyperactive and is a victim of auditory and visual hallucinations. The alcoholics could be heard shouting that cockroaches are crawling upon them; they see red lions and they may seriously believe that they are being attacked by dangerous animals or people. They are completely disoriented.

Progressively, the alcoholic becomes weaker, agitated and confused. These syndromes coupled with exhaustion and fever are called ‘tremulus delirium’. In physical dependence the intensity of the syndromes associated with withdrawal as typified by tremulus delirium is related to the duration and level of alcohol abuse. Physical dependence could develop from ethanol induced alterations in membrane components and functions (Cargiulo, 2007).

Alcoholics usually exhibit increased resistance to the intoxicating effects of alcohol and are often sober at blood alcohol concentrations that could be deadly in naïve occasional drinkers. Indeed, chronic alcohol abusers can readily ingest quantities of alcohol that would severely intoxicated the occasional drinker (Chiao Chicy and Shijian, 2008).

Ethanol can cross the blood- brain barrier and enter the brain quickly. Blood alcohol level is almost always directly proportional to the concentration of alcohol in brain tissue (Oscar Berman and Marinkovic, 2003). However, despite increasing levels of alcohol in the blood, alcoholics usually exhibit decreasing response to the intoxicating effect of alcohol.

This phenomenon known as tolerance could be explained in part by these mechanisms: first, tolerance could develop consequent upon alterations in the absorption rate, distribution, metabolism and elimination of alcohol from the body (Rottenburg, 1986). The resultant effect of these alterations is a reduction in the duration and intensity of alcohol’s effects on the body tissues most remarkably the brain.

The second mechanism involves alterations in the properties or function of tissues rendering them less vulnerable to effects of alcohol (Wilson et al., 1984). Tolerance to alcohol could develop as a result of adaptive alterations in the central nervous system. Alcohol changes many specific membrane dependent processes such as Na+, K+ ATPase and adenylate cyclase process in the cell precipitating ethanol-induced alterations in neural functions. It has been observed that after chronic exposure to alcohol, cellular membranes often develop resistance to the fluidizing effect of alcohol (Goldstein, 1986). Ethanol-induced alterations also occur in membrane components and functions such as alterations in membrane lipids, receptors, phosphatidylinositol, GTP binding proteins, second messengers and neuromodulators (Reynolds et al., 1990). Alterations in ion channels and transporters are also some of the ethanol induced changes in human cell membranes related to tolerance (Chastain, 2006). Putting these observations in a functional perspective, it is salient to point out the fact that these adaptive changes in membrane components are exquisite phenotypic markers for genetic predisposition to alcoholism and its attendant problems (Das et al., 2008).

1.1.5 Aetiology/Causes of Alcohol Abuse

1.1.5.1 Biochemical basis

(a) Monoaminergic System

The enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO) is the major degradative enzyme for both catecholamines and indoleamines. It has been shown that reduced platelet monoamine oxidase concentrations are closely associated with a remarkable predisposition to alcoholism (Patsenko, 2004) and psychiatric vulnerability. It has also been proposed that a weak monoaminergic system causes predisposition to alcohol abuse (Raddatz and Parini, 1995).

Available evidence is becoming overwhelming in support of the view that sub class of alcoholics exists where genetic considerations are of etiological significance. These imposing factors appear to be reflected in low platelet monoamine oxidase (MAO). Low concentrations of platelet monoamine oxidase reflect a disturbance in the serotoninergic system (Chastain, 2006). Thus, the biochemical basis of alcoholism seems to involve combined aberrations in some transmitter system. In essence, these aberrations have far reaching effects which are reflected in neuro-physiological, psychosocial and personality abnormalities.

Biologically active chemicals called tetrahydroisoquinolines are formed during alcohol metabolism (Antkiewicz et al., 2000). Catecholamines could also condense with aldehydes via a Pictet-Spengler reaction to form 1,4-Disubstituted tetrahydroisoquinoline (Raddatz and Parini, 1995). Tetrahydroisoquinoline such as tetrahydropapaveroline changes drinking behaviour from alcohol rejection to alcohol acceptance (Nappi and Vass, 1999).

The Pictet-Spengler reaction provides a useful route for the synthesis of tetra hydroxy quinoline (TIQ). Many tetrahydroisoquinoline are formed from dopamine and carbonyl compounds (phenylpyruvic acids, aldehydes and ketones) two catecholamine norepinephrine or epinephrine could also react resulting in the formation of diastereomeric TIQ as shown below

Fig. 1: 1,4-disubstituted TIQ occur in form of two diastereomers and their optical isomers. Furthermore, ethanol or its first oxidation product acetaldehyde can induce catecholamines to undergo an unusual form of metabolism that results in the formation of 1,2,3,4- tetrahydroisoquinoline. Tetrahydroisoquinoline compounds have biochemical and neuropharmacological properties. They possess abilities to interact with catecholaminergic and dopaminergic systems. They also exert a potent influence on Ca2+ binding in synaptosomes in a similar manner to morphine and ethanol. T1Qs have biochemical associations with ethanol and is deeply involved in the aetiology of alcoholism (Raddatz and Parini, 1995).

Patsenko (2004) showed that excessive and chronic consumption of alcohol by human alcoholics could be caused by metabolic abnormalities that result in the formation of tetrahydroisoquinolines. He reasoned that because drinking generates tetrahydroisoquinolines and tetrahydro isoquinolines stimulate drinking, the positive feedback loop could be responsible for the obsessive, uncontrolled and habitual drinking by alcoholics. Thus, tetrahydroisoquinolines could be involved in the mediation of voluntary ethanol consumption habit that often degenerates to heavy intoxication, physical dependence and tolerance (Chastain, 2006).

- Alcohol: An Etiological Factor in Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse

The positive reinforcing properties of alcohol are largely responsible for the cravings and tendency to ingest more and more alcohol. Alcohols depress the inhibition centres of the brain and produce a feeling of euphoria. By shattering the shackles of inhibition and self restraint, ingestion of alcohol leads to further ingestion; and feelings of excitement and self confidence continue to reign supreme. Laughter, lively gesticulation and loquacity then flow. Indeed, the intoxicating effects of moderate imbibing of alcohol is rewarding to the consumers (Fowkes and Steven, 2012).

Essentially, most studies of alcohol as a drug of abuse are based on the premise that humans ingest alcohol due to its reinforcing or rewarding properties. There are considerable interest in the similarities between alcohols reinforcing properties and those of other drugs of abuse. There is a marked resemblance between the reinforcing effects of alcohol and those of opiate drugs (Giflow, 2006).

It has been noted that the positive reinforcing potential of alcohol is partly the cause of the strong desire and inclination individuals have for alcohol consumption. However, it is actually a metabolite of ethanol called acetaldehyde rather than ethanol itself which mediates this reinforcing effect (Goedde and Agarwal, 1983).

Increased interest has been ignited in the biochemical pharmacology of acetaldehyde, the oxidation product of ethanol and in the part it may play in alcohol intoxicating effects, physical dependence and tolerance. Acetaldehyde is a toxic substance which when it occurs in a relatively high levels in the circulation induces a characteristic set of aversive physiological reactions (Harada et al., 1983). So ordinarily, it is expected that the toxic effects of acetaldehyde should lead to attenuation of voluntary alcohol ingestion. However, contrary to expectations, there are some unfolding evidence that acetaldehyde may be directly involved in voluntary ethanol consumption (Thacker et al., 1984).

While the accumulation of acetaldehyde, the oxidation product of ethanol, in circulation discourages ethanol ingestion, the presence of acetaldehyde in the brain strongly supports voluntary alcohol intake, physical dependence and tolerance (Harade et al., 1983).

1.1.5.2 Psychosocial Basis of Alcohol Abuse

(a) Temperament

Myriads of definitions and characterizations of temperament have been attempted ever since ancient philosophers first considered the origins of psychological individuality. One definition that embraces an individual’s style of psychological functioning was furnished by Kandel et al. (2001) in which they showed that temperament is the characteristic phenomena of an individual’s nature, including his susceptibility to emotional stimulation, his customary strength and speed of response, the quality of his prevailing mood, and all the peculiarities of fluctuations and intensity of mood, these being phenomena regarded as dependent on constitutional make up and therefore largely hereditary in origin (Kandel et al., 2001).

This definition of temperament captures the central features of temperament, including behaviour and mood. In other words, one could proffer that individual differences in temperament reflect variability in neurobiological processes that possess strong genetic link (Tarter et al., 1994).

Aberration in temperament trait expression paves the way for a developmental trajectory that may culminate in non normative behaviour such as anxiety and alcohol abuse. A defect in temperament is closely associated with negative mood, slow adaptability, high intensity of emotional reactions and alcohol abuse (Cosci et al., 2007). This constellation of temperament features is related to a heightened risk for conduct problems (Maziade et al., 1990) and alcohol abuse (Lerner and Vicary, 1984; Windle, 1992; Tarter et al., 1994).

Deviations in temperament are typically connected with high susceptibility to maladjustment and psychopathology. In fact, aberrant behaviour and alcoholism are common among individuals with defective temperament disposition (Maziade et al., 1990). Significantly, a difficult temperament is intricately associated with a special predisposition to develop oppositional behavioural abnormalities (Maziade et al., 1984). These aberrant behaviour manifestations usually occur in conjunction with chronic abuse of alcohol, physical dependence and tolerance to alcohol (Das et al., 2008).

- Disruptive Home Environment

Defective marital adjustment influences the subsequent development of difficult behaviours (Esterbrooks and Ende, 1988). Disruptive home environment has deep impacts on the development of the family members. Marriages are almost always dysfunctional and conflict-laden where both or one of the partners is alcoholic. No doubt, good child rearing in such home is often adversely affected. It has been shown that children are perceived negatively after a heated quarrel between parents that are alcoholic (Markman and Jones Leonard, 1985). Under these unfortunate conditions, coercive and aversive child-rearing strategies are usually adopted by the disillusioned and near paranoid parents leading to maladjustment in the children. As a vicious-circle, such children develop to become well entrenched edifice of violence and viable precursors of alcoholism. This in part accounts for the reasons why alcoholism seems to be perpetuated in some families (Blackson et al., 1994).

Adverse relationships with the environment and poor adjustments typically herald alcohol abuse. Indeed, adverse person-environment cohabitants could make an individual susceptible to aberrant psychological development. Those who experience aggression are often more likely than others to perpetrate aggression (Stewart and Deblois, 1981). Such individuals usually resist authority figures and are prone to alcohol abuse (Billman and McDevitt, 1980).

It is expedient to point out that environmental factors interact chronologically with behavioural traits to place an individual onto a trajectory toward alcohol abuse (Blackson et al., 1994).

1.1.5.3 Genetic Factors

Alcoholism is rather a complex, heterogeneous disease. Familial aggregation of alcohol abuse has been noted for a long time and has led to the belief that the tendency to abuse alcohol is heritable (Nurnberger et al., 2007). Some families do have a disproportionate amount of alcohol abuse.

Nurnberger et al. (2007) showed that twenty four percent of sons of alcoholics adopted into non-alcoholic homes themselves became alcoholic. It is indeed difficult to conceptualize anything but genes connecting the adopted-away son with his birth father. Furthermore, there are manifestations of genetic influences on specific aspects of alcohol-related behaviour For instance, there are genetic influence on the quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption (Dick and Bierut, 2006).

1.1.6 Effects of Alcohol

1.1.6.1 The Effects of Ethanol on the Central Nervous System

The quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption are affected by the interaction of the rewarding and aversive experiences derived from drinking (Enoch, 2006). The central nervous system (CNS) is markedly affected by alcohol consumption. Alcohol causes sedation and relief of anxiety. At higher concentrations, alcohol can lead to slurred speech, impaired judgement and disinhibited behaviour. Like other sedative-hypnotic drugs, alcohol is a CNS depressant. Ethanol affects a large number of membrane proteins that participate in signalling pathways including neurotransmitter receptors for amines, amino acids, opioids and neuropeptides enzymes such as phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C, adenylyl cyclase, Na+, K+ATPase, nucleoside transporter and ion channels (Sakmann, 1992).

Ethanol also has effects on neurotransmission by glutamate and GABA, the main excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters in the CNS. Ethanol exposure enhances the action of GABAA at GABA receptors which are consistent with the ability of GABAA antagonists to attenuate some of the actions of ethanol. Ethanol inhibits the cation channel associated with the N-Methyl-D- aspartate (NMDA) subtype of glutamate receptors. The NMDA receptor is involved in many aspects of cognitive function including learning and memory. “Blackouts”-periods of memory loss that occur with high levels of alcohol-results from inhibition of NMDA receptor activation (Michel et al., 1998).

Although, alcohol is transported to all parts of the body after its consumption, the effects of alcohol on the brain are most evident. The human brain is extremely sensitive to the intoxicating effects of alcohol. Contrary to popular belief, alcohol is always a central nervous system depressant (Glavas and Weinberg, 2006). Some extremely sophisticated areas of the brain concerned with the restraint of natural impulses seem to have low threshold to alcohol-induced depression (Fergusson et al., 2009). This accounts for the apparent stimulation observed with moderate alcohol consumption and for the depression evident after imbibing high concentration of alcohol. The increased activity, loud laughter and long unending speech observed after moderate drinking of alcoholic beverages should not be perceived as a consequence of central nervous stimulation. Alcohol rather depresses or inhibits the inhibitory centres of the brain. This shatters the shackles of self restraints and produces apparent stimulation (Glavas and Weinberg, 2006).

In small quantities, alcohol produces a feeling of euphoria, good fellowship, and increased, albeit unjustified self-confidence. For some individuals, modest alcohol ingestion serves as an effective and efficient catalyst or defroster for promoting physical activities and overcoming inhibitions that act as barriers to successful performance of certain tasks (Glavas and Weinberg, 2006). However, ingestion of large quantities of alcohol interferes with the normal process of information integration by the cerebral cortex (Crews et al., 2007). Thinking ceases to be systematic and becomes disorganised and

confused. With progressively greater quantities of alcohol, concentration, memory, judgement and perspective are grossly blunted. Excessive consumption of alcohol leads to impairment of motor coordination, movement become uncertain leading to staggering and total inability to move. The alcoholics’ personality is thus compromised (Kushner et al., 2000). Indeed, alcohol reduces both mental and physical efficiency.

Alcohol acts on virtually every single cell of the body, but the central nervous system is the target most affected. In fact, alcohol affects almost every level of the nervous system. It affects the neuro-chemicals within single cells as well as the macro-functions controlling thought processes and behaviour (Guerri and Pascual, 2010). Alcohol distorts judgement and impairs information processing and reaction time. Actually, alcohol can lead to alteration in brain response to visual and auditory stimuli (Verbaten, 2009).

Chronic and excessive consumption of alcohol can lead to two biochemically and neuro-pathologically distinguishable chronic organic brain syndromes namely: alcohol amnestic syndrome (also called Korsakoff’s psychosis) and alcoholic dementia (Panza et al., 2009).

- Microanatomy of the Kidney

The kidneys are paired organs situated on either side of the vertebral column extending from the twelfth thoracic to the third lumbar vertebrae (Tisher and Madsen, 1996). Principally, the kidneys excrete the waste products of metabolism, precisely regulates the body’s concentration of water and salt, maintain the appropriate acid-base balance of plasma and serve as endocrine organs secreting such hormones as prostaglandins erythropoietin and renin (Glodny et al., 2009).

The physiologic mechanisms that the kidneys have evolved to carry out these functions require a high degree of structural complexity. Basically, the ureter enters the kidney at the hilum and dilates into a funnel- shaped cavity, the pelvis, from which is derived two or three main branches, the major calyces; each of these subdivided again into three or four minor calyces (Knight et al., 2003).

Essentially, the kidney is made up of a cortex and a medulla. Within the cortex, two main zones can be distinguished namely:

- The cortical Labyrinth, composed of the glomeruli, convoluted tubules and associated vessels; and

- The medullary rays composed of parallel groups of the straight segments of proximal tubule (pars recta) and thick ascending (distal) tubules as well as collecting ducts.

The medulla consists of renal pyramids, the apices of which are called papillae. Each papilla projects into a minor calyx. Cortical tissue extends into spaces between adjacent pyramids as the renal columns of Bertin.

The outer medulla can be divided into an outer (Juxta – Cortical) stripe and an inner stripe. The out er stripe contains the proximal straight tubule and the medullary thick descending limb. The inner stripe contains the thin segments of the descending limb tubule and the thick ascending limb (loop Henle) (Greger, 1985). The vascular bundle consists of descending and ascending vasa recta surrounded by pars recta, the descending limb and the thick ascending limb. Further away are the collecting tubules. The inner medullar contains the thin limbs of long loops (of Henle) both ascending and descending.

The nephron is the basic structural and functional unit of the kidney. Each nephron consists of a renal corpuscle, comprising Bowman’’s capsule, the glomerular capillary tuft and a renal tubule. Each capsule communicates with the tubule and then the renal calyx via the collecting tubule and duct (Howie and Rollason, 1993).

The tubular segments are structurally, cytologically and functionally distinct. The renal tubule extends into or towards the medulla and loops (the loop of Henle) back to its own renal corpuscle before draining into a collecting tubule. The loops may be long or short. The short loop of Henle turns at the junction of outer and inner medulla. The long loops extend into the inner medulla (Jamison and Kriz, 1982).

The renal corpuscle is the term properly used to describe Bowman’s capsule and the capillary tuft (the glomerulus). Bowman’s capsule consists of parietal epithelial cells and a basement membrane which is reflected onto the glomerulus becoming continuous with the glomerular basement membrane in the point of entry of the afferent and efferent arterioles (the vascular pole). Bowman’s capsule invests the glomerulus and is continuous with the proximal tubule at the tubular orifice (pole) which is found opposite the vascular pole. The Bowman’s capsule is lined with a layer of flattened epithelium the parietal podocytes (Gibson et al., 1992).

The glomerular capillary tuft arises from the afferent arteriole. The capillary loops are lined with an endothelium that has a highly specialized basement membrane and visceral epithelial podocytes. The capillaries then recombine to form the efferent arteriole. The capillary loops are supported by the mesangium which is composed of basement membrane such as matrix in which are embedded mesangial cells. At the vascular pole, mesangial cells form part of the juxtaglomerular apparatus (Jamison and Kriz, 1982).

The juxtaglomerular apparatus is largely concerned with blood pressure and circulating fluid volume control (Schnermann and Briggs, 1985). The components of the juxtaglomerular apparatus are:

- The terminal portion of the afferent arteriole and efferent arteriole.

- The macula densa, a specialized segment of the distal tubule.

- The extraglomerular mesangial cells at the vascular pole and

- The sympathetic nerve supply.

The tubule of the nephron comprises the following segments from the glomerulus:

- The proximal tubule (convoluted section), the proximal tubule (straight part), also known as pars recta,

- The descending thin limb of Henle’s loop (in long – loop nephrons only).

- The medullary thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop.

- The cortical thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop.

- The distal convoluted tubule.

The collecting duct system begins with the connecting tubule. This segment, which is poorly defined in the human kidney, resembles the distal convoluted tubule (Howie and Rollason, 1993). The connecting tubule drains into the cortical collecting duct, which passes from the cortex into the outer medulla. On reaching the inner medulla, paired fusions of collecting ducts occur forming the inner medullary collecting ducts which drain into the renal papillae which form the apices of the renal pyramids (Gosling et al., 1982).

The basement membrane of Bowman’s capsule is a multilayered structure which is continuous with the glomerular basement membrane at the vascular pole and with the basement membrane of the proximal tubule. The visceral podocytes, the glomerular, the glomerular basement membrane and the endothelial cell lining, together function as a complex filter in the Bowman’s capsule (Batsford et al., 1987). The podocyte are responsible for formation of the glomerular basement membrane.

Cell body of the podocyte has a number of wide processes which embrace the capillary. The pedicels arise from the subdivisions of these processes. The pedicels from adjacent podocytes are arranged alternately. The filtration slit diaphragm separates adjacent pedicels. This is considered to be the site of ultrafiltration (Shikata et al., 1990).

The glomerular basement membrane (GBM) is composed of three distinct layers: the central lamina densa and on the side; less dense zones, the lamina interna rara and lamina externa rara. The main structural component of the glomerular basement membrane is collagen type 4 which is tightly packed in the lamina densa, and has a looser arrangement in the laminae interna and externa. Importantly, collagen type 4 contains a non collagenous domain in which is found the goodpasture antigen (Pusey et al., 1987). Other adhesion molecules such as laminin, fibronectin indicating, amyloid P substance (Kaufman et al., 1995) and the negatively charged heparan sulphate proteoglycan are present. The lamina externa has a net negative charge from numerous polyanionic sites (Gibson et al., 1992).

The glomerular capillaries are lined by endothelial cells. The cytoplasm of the endothelial cell is perforated by numerous fenestrations. The endothelin -1 produced by the glomerular endothelial cells influences adjacent mesangial cells (Ballermann and Marsden, 1991). The glomerular mesangium is analogous to the intestinal mesentery; it provides support for the glomerular capillary loops. The presence of the actin and myosin in the mesangial cells indicates a contractile function. And the contraction of the mesangium influences glomerular capillary flow and filtration (Kreisberg et al., 1985). The cells of the proximal tubule vary in structure corresponding to the convoluted segment, a transition zone and the straight part. A typical proximal tubular cell is columnar with a basal nucleus.

Finally, the collecting ducts are composed of a mixture of intercalated cells and principal (collecting duct) cells. The main feature of the polygonal principal cell is the numerous regular infoldings (basal labyrinth) of the basal cell membrane (Kloth et al., 1993).

- Vulnerability of the Kidney to Alcohol Toxicity

There exist a good number of reasons why the kidney is uniquely vulnerable to the hazards of alcohol toxicity. First, it receives a high percentage of the total cardiac output. Indeed, the kidney has a rich blood supply. This means that the kidney could readily be exposed to large quantities of alcohol even if peak circulating levels are only maintained momentarily (Chung, 2005). Secondly, the hypertonicity of the medullary interstitium which is generated by operation of the countercurrent mechanism operates to concentrate alcohol and its toxic metabolite called acetaldehyde in the relatively hypovascular area of the kidney. Thus renal tubular cells could become exposed to alcohol concentrations which are more than those found in any other tissue or cells (Busse et al., 2002).

Also, the pivotal role of the kidney as an obligatory route for the passage of some drugs including alcohol implies that in renal dysfunctions with less perfusion, excretion of alcohol is slowed and if other extra renal mechanisms of elimination are not mobilized, alcohol accumulation will occur. The high concentrations of alcohol in circulation therefore render the kidney more vulnerable to direct and unmitigated damage (Cushman, 2001).

- Renal Function Tests as Indicator of Alcohol Induced Kidney Injuries

Laboratory tests play crucial roles in the diagnosis and assessment of renal dysfunction under excessive and consistent alcohol consumption because clinical signs and symptoms may be vague or absent. Some of the renal function tests reveal primarily disturbances in glomerular filtration (Kluth, 1999) while others reflect dysfunction of the tubules. However, it is important to highlight the fact that renal damage is seldom confined solely to a particular portion of the nephron because the anatomic portions of the nephron are closely related and have common blood supply so damage to one portion gradually involves the nephron as a whole (Remuzzi et al., 1997). Eventually both glomerular and tubular portions of the nephron become involved irrespective of the site of the initial damage. The kidney has a high reserve capacity; hence early toxicities may not be immediately notice by clinical examination. Since the kidney is a common target of toxic chemicals such as alcohol (Fergusson et al., 2009), a need exist for the inclusion of sensitive and reliable tests to ascertain the level of alcohol induced renal dysfunctions (Levey, 1990).

- How Alcohol Induced Nephropathies Affect Glomerular Filtration

The glomerular filters usually retain within the circulation all cells and all proteins of the plasma, but allow free passage of water and solutes. The glomerular capillary wall is highly specialized in that the endothelial cells are reduced to a thin fenestrated sheet of cytoplasm, while on the external surface of the capillary, unique cell, the podocyte epithelial cell, whose surfaces are directed towards the capillary basement membrane form an intricate series of interlocking foot processes; thereby constituting a filter (Tryggvason and Wartiovaara, 2001).

The glomerular filter also functions as a charge-selective and size-selective barrier. Smaller molecules and those with a small negative or even a net positive charge at physiological pH will pass more easily through the glomerulus. However, since at the pH of plasma most proteins carry a net negative charge, charge selectivity is most important in determining the retention of plasma protein molecules. Thus the penetration of negatively charged macromolecules is hindered and that of positively charged molecules facilitated. So the glomerular filtrate is almost devoid of protein. The charge and size selective barrier of the glomerular filter is mostly disturbed in alcohol induced nephropathies (Tryggvason and Wartiovaara, 2001).

- Determinants of Glomerular Filtration

As in all capillary beds, the determinants of glomerular ultrafiltration are first the net ultrafiltration pressure, second the hydraulic permeability of the capillary wall and the third is the area of available filtering surface (Brenner et al., 1986). The hydraulic permeability of the glomerular capillaries is much higher than that found in other capillary beds, emphasizing the specialized function of the glomerulus as a filter. The ultrafiltration pressure depends in turn upon the hydrostatic pressure operating across the glomerular capillary wall and the osmotic pressure of the plasma proteins (Deen and Sarat, 1981).

One of the other crucial determinants of the glomerular filtration rate is of course the renal blood flow and hence plasma flow (Schnermann and Briggs, 1985). Obviously dilation of the efferent arteriole will increase glomerular blood flow, decrease the net ultrafiltration pressure and hence reduce glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Similarly efferent arteriolar constriction will raise the net ultrafiltration pressure and increase GFR. Exactly opposite effects will be seen from afferent arteriolar dilation or constriction, the former leading to an increase in GFR and the latter to a reduction. The interplay between these pre and postcapillary sphincters can permit exquisite regulation of glomerular blood flow and glomerular filtration rate; this can be affected by alcohol ingestion (Steinhausen et al., 1988).

- Creatinine Clearance as a Measure of Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR)

Ever since the useful suggestion of Popper and Mandel (1937) that the clearance of endogenous creatinine approximates to the glomerular filtration rate, creatinine clearance has been very popular in the assessment of renal dysfunctions. Creatinine is a waste product of muscle metabolism formed by the non-enzymatic dehydration of muscle creatine. Creatine itself is synthesized in the liver and transported to the muscle (Levey et al., 1988); the main determinant of the creatine pool, therefore, is muscle mass. The only other source of creatine is, of course, meat from dietary sources.

Creatinine is freely filtered and is not reabsorbed within the renal tubule. However, in some animal species including humans there is limited tubular secretion of creatinine. Essentially, renal clearance is the volume of plasma that is completely cleared of a particular substance in a given time period (usually one minute), by the kidney (Chung et al., 2005).

The clearance (C) of a substance (X) can be calculated as shown below:

Where UX and PX are the urine and the plasma Concentrations of X and V is urine flow rate.

The clearance of a substance that is freely filtered at the glomerulus but once within the tubule is neither reabsorbed nor secreted can be used as a marker for measurement of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (Chung et al., 2005). The 24-hour creatinine clearance (obtained by collection of complete 24-hour urine) is widely used as a measure of GFR. In normal non pregnant adult, the rate of creatinine excreted by the kidneys is equal to the rate of creatinine produced by muscle metabolism. Thus plasma creatinine concentration remains constant when renal function begins to deteriorate due to alcohol mediated nephropathies, the excretion of creatinine falls, leading to an increase in plasma creatinine. Mild to moderate levels of renal impairment usually lead to small increases in plasma creatinine, but with severe renal disease, plasma creatinine changes markedly and thus the plasma creatinine value can be used as a clinical index glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (Nielsen et al., 1999).

The amount of a substance excreted through the kidneys is the product of the urine flow rate (V), and the concentration of that substance in the urine (U). The quantity (UV) is the excretion per unit time. The concept of renal clearance (C) expresses the relationship between the excretion per unit time and the concentration in the plasma, which is obviously an index of the kidney’s ability to ‘clear’ the blood of any substance (Chung et al., 2005).

The power of this concept of renal clearance is that it can be used to express the relative ability of the kidney to excrete any substance and this could be used to ascertain the structural and functional integrity/status of the kidney under excessive and consistent alcohol consumption (Hallan et al., 2004).

- Serum Electrolyte and Alcohol-Induced Renal Dysfunctions

Actually, filtration occurs as the blood flows through the glomerulus. During the passage of glomerular filtrate through the convoluted tubule, the medullary loop and the collecting tubule, selective reabsorption occurs leading to alteration in the volume and composition of the glomerular filtrate. The general purpose of this process is to reabsorb into the blood those filtrate constituents required by the body to maintain fluid, nutrient, electrolyte balance and the pH of the blood (Verbalis, 1990). Active transport is carried out at carrier sites in the epithelial membrane using chemical energy to transport substances against their concentration gradients (Sun et al., 2004).

Some constituents of glomerular filtrate do not normally appear in the urine because they are completely reabsorbed. The kidneys’ maximum capacity for reabsorption of substances is called the transport maximum or renal threshold. If, the concentration of substances rises above the transport maximum, the substance will start to appear in the urine because all the carrier sites are occupied and the mechanism for active transfer out of the tubule is overloaded (Wingo and Smolka, 1995).

However, the reabsorption of water is entirely passive; following osmotically the entirely active absorption of Na+. Sodium is the most common cation in extracellular fluid and potassium is the most common intracellular cation. Some complex mechanisms in the kidney assist to maintain the concentrations of sodium and potassium within physiological limit. The mechanisms of Na+ reabsorption is heterogeneous, differing in the various nephron segments. In the proximal tubular luminal absorptive process, Na+ is taken up mainly in exchange for protons. In the early distal tubule, luminal NaCl reabsorption proceeds via a NaCl cotransport system. In the collecting duct, only a small percentage of the filtered NaCl is reabsorbed (Tannem, 1991).

The distal convoluted tubule is lined by a tall cuboidal epithelium and possesses the greatest Na+ K+-ATPase activity (Greger and Velazquez, 1987). Cells in the afferent arteriole of the nephron are stimulated to produce the enzyme renin by sympathetic stimulation, low blood volume or by low arterial blood pressure. Renin converts the plasma protein angiotensinogen, produced by the liver to angiotensin I. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE), formed in small quantities in the lungs and proximal convoluted tubules converts angiotensin I into angiotensin II. Angiotensin II stimulates aldosterone and aldosterone stimulates sodium reabsorption from the lumen of the distal renal tubule in exchange for either potassium or hydrogen ion. Alcohol-mediated distal tubule dysfunction leads to impaired response to aldosterone affecting the reabsorption of the sodium and the urine then contains an inappropriately high concentration of sodium (Tannem, 1991).

Potassium is the most prevalent ion in animal cells and the most crucial in generating the resting potential difference across the plasma membrane of cardiac, neuromuscular and polarized epithelial cells. Changes of a mere 1 or 2 mEq/L from the range of serum potassium concentration could progress unnoticed until suddenly and without warning the situation turns perilous. In view of the small quantity of K+ in the extracellular fluid (ECF), ingestion of K+ could lead to a dangerous elevation in serum K+, were it not for the mechanism that influence K+ distribution between ECF and intracellular fluid (ICF); some of the ingested K+ temporarily enter the cells. Eventually, the excess K+ is excreted primarily by the kidney. Potassium undergoes simultaneous reabsorption and secretion by the renal tubule – the bidirectional transport (Giebisch an d Wang, 1996). Different cells in the collecting duct are either potassium secretory or absorptive (Giebisch et al., 1991).

There is a basic pump-leak system common to the epithelial cells lining the renal tubule (Bertorello and Katz, 1993). Na+, K+ -ATPase is located on the lateral and blood-facing (basal) cell membrane only, i.e., not on the tubule lumen-facing (apical) membrane. The Basolateral Na+, K+ – ATPase drives Na+ out and 2K+ in, creating a cell interior low in Na+, high in K+ and electrically negative with respect to the tubule fluid (Blanco and Mercer, 1998).

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis also plays a major role in regulating K+ excretion. Precisely, aldosterone stimulates K+ secretion (excretion/removal or loss). It is important to point out that alcohol-induced proximal tubular dysfunction among other features is significantly marked with impaired reabsorption of potassium leading to hypokalemia (Stoke, 1982). Hypokalemia in turn impairs nerve and neuromuscular transmission, cardiac conduction and muscular contraction. Muscular weakness and ileus of the intestine are typical clinical manifestations of hypokalemia resulting from proximal tubular dysfunction caused by chronic alcohol abuse (Wingo and Smolka, 1995).

- Alcohol-Induced Pathological Proteinuria

Proteinuria represents the single most useful indicator of the presence of an injury to the kidney. Such injury impairs the barrier to protein passage imposed by the walls of glomerular capillaries (Shankar et al., 2006). The glomerular capillary wall is highly specialized in that the endothelial cells are reduced to a thin fenestrated sheet of cytoplasm. The glomerular filter functions both as a charge- selective and size-selective barrier. Consequent upon this, the loss of most plasma proteins through the glomeruli is restricted by the size of the pores and by the charge on the basement membrane (Guasch et al., 1993). Alteration of any one of these factors by alcohol-mediated glomerular dysfunction could allow albumin and larger proteins to enter the filtrate.

Actually, proteinuria could be precipitated as a result of glomerular dysfunction or impaired protein reabsorption of protein by the proximal renal tubule. The hallmark of ‘tubular proteinuria’ is th e presence of a number of proteins of a lower molecular weight than albumin in urine (Kaysen et al., 1991). This contrasts with glomerular proteinuria in which albumin is the predominant species.

The proximal renal tubule is a major catabolic site for several plasma proteins which, by virtue of their small size and favourable isoelectric point, are filtered freely by the normal glomerulus (Bingham and Cummings, 1985). When there is proximal tubular dysfunction due to alcoholic toxicity, the reabsorption of these proteins could be impaired; and they appear in increased quantities in urine. Put in a functional perspective for differential diagnostic purposes, it is important to point out the fact that the plasma levels of small molecular weight proteins rise if glomerular filtration rate is impaired as a result of chronic and excessive alcohol ingestion. However, if there is a selective proximal renal tubular impairment due to alcohol abuse, it is the urinary, not plasma levels, which rise (Knight et al., 2003).

Essentially, glomerular damage is the most common cause of pathological proteinuria. Glomerular filter operating as both size-selective and charge-selective barrier normally prevents the passage of large protein molecules. So the large proteins commonly found in proteinuria could be as a result of glomerular dysfunction (Guasch et al., 1993). Physical impedance to the passage of larger molecules through the filter arises through the ordered arrangement of type IV collagen and its glycol-protein matrix in the outer and inner laminae rarae and by the more tightly structured, principally type IV collagen of the central lamina densa of the glomerular basement membrane. The net effect is a rate dependent exclusion of some proteins. Globular proteins appear to be excluded more readily than those of elongated or tubular shape

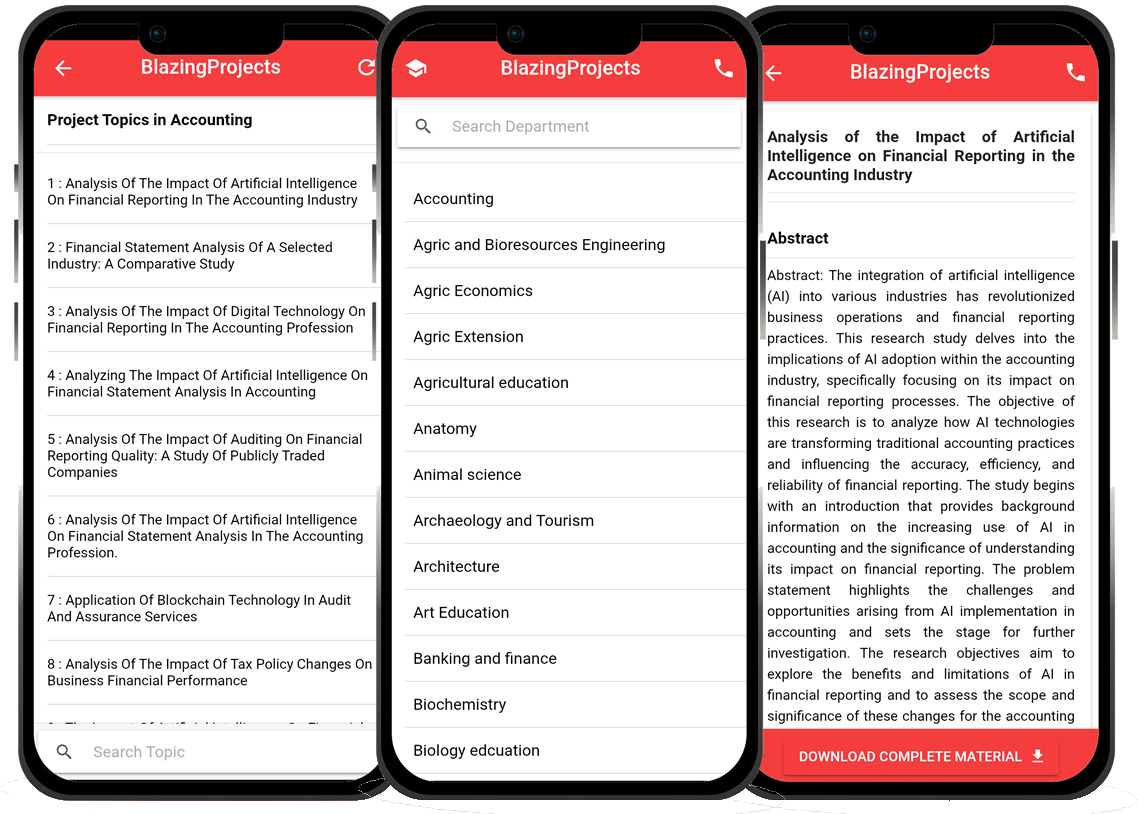

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Research Thesis

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Thesis-to-Journal Publication

🎓 Undergraduate/Postgraduate Thesis

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Exploring the Role of Gut Microbiota in Human Health and Disease...

The project titled "Exploring the Role of Gut Microbiota in Human Health and Disease" aims to investigate the intricate relationship between gut micro...

Investigating the role of microRNAs in regulating gene expression in cancer cells....

The project "Investigating the role of microRNAs in regulating gene expression in cancer cells" aims to delve into the intricate mechanisms by which m...

Exploring the Role of Epigenetics in Cancer Development and Treatment...

The project titled "Exploring the Role of Epigenetics in Cancer Development and Treatment" focuses on investigating the intricate relationship between...

Analysis of the role of microRNAs in cancer progression...

The project titled "Analysis of the role of microRNAs in cancer progression" aims to investigate the intricate role of microRNAs in the progression of...

Investigating the role of microRNAs in regulating gene expression in cancer cells....

**Research Overview: Investigating the Role of microRNAs in Regulating Gene Expression in Cancer Cells** Cancer is a complex disease characterized by uncontrol...

Exploring the role of microRNAs in regulating gene expression in cancer cells...

The project titled "Exploring the role of microRNAs in regulating gene expression in cancer cells" aims to investigate the intricate mechanisms by whi...

Exploring the Role of MicroRNAs in Cancer Progression: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Po...

The project titled "Exploring the Role of MicroRNAs in Cancer Progression: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential" aims to investigate the intricate inv...

Exploring the role of microRNAs in cancer progression and potential therapeutic appl...

The project titled "Exploring the role of microRNAs in cancer progression and potential therapeutic applications" aims to investigate the intricate in...

Exploring the role of gut microbiota in metabolic diseases...

The project titled "Exploring the role of gut microbiota in metabolic diseases" aims to investigate the intricate relationship between gut microbiota ...