EVALUATION OF THE TRACE – ELEMENT COMPOSITION OF THE LEAF EXTRACT (A FOCUS ON PIPER METHYSTICUM (AWA))

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Trace Elements2.2 Importance of Trace Elements in Plants

2.3 Methods of Trace Element Analysis

2.4 Previous Studies on Trace Element Composition

2.5 Role of Trace Elements in Plant Physiology

2.6 Effects of Trace Element Deficiency in Plants

2.7 Bioavailability of Trace Elements in Soil

2.8 Toxicity of Trace Elements in Plants

2.9 Trace Element Uptake Mechanisms

2.10 Applications of Trace Element Research

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Design3.2 Sampling Techniques

3.3 Data Collection Methods

3.4 Data Analysis Procedures

3.5 Experimental Setup

3.6 Quality Control Measures

3.7 Ethical Considerations

3.8 Limitations of Research Methodology

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Analysis of Trace Element Composition4.2 Comparison with Existing Studies

4.3 Interpretation of Findings

4.4 Relationship between Trace Elements

4.5 Factors Affecting Trace Element Absorption

4.6 Implications for Plant Health

4.7 Future Research Directions

4.8 Recommendations for Practice

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Findings5.2 Conclusion and Interpretation

5.3 Contributions to Knowledge

5.4 Practical Implications

5.5 Areas for Future Research

Thesis Abstract

AbstractPiper methysticum, also known as Awa or Kava, is a plant native to the Pacific islands and is traditionally used for its medicinal and psychoactive properties. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the trace-element composition of the leaf extract of Piper methysticum to better understand its potential health benefits and toxicological implications. The trace-element composition of the leaf extract was analyzed using various analytical techniques including atomic absorption spectroscopy and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. The results revealed the presence of essential trace elements such as zinc, copper, and manganese, which are known to play crucial roles in various physiological processes in the human body. Additionally, the presence of potentially toxic elements such as lead and cadmium was also detected, albeit at low concentrations. The findings suggest that the leaf extract of Piper methysticum contains a diverse array of trace elements that may contribute to its pharmacological effects. Furthermore, the study investigated the potential health risks associated with the consumption of Piper methysticum leaf extract due to the presence of trace elements. The levels of toxic elements detected were below the acceptable daily intake limits set by regulatory authorities, indicating that the consumption of the leaf extract is unlikely to pose significant health risks when used in moderation. Overall, this study provides valuable insights into the trace-element composition of the leaf extract of Piper methysticum and highlights the importance of considering trace elements in the evaluation of the health benefits and potential risks associated with the use of traditional herbal remedies. Further research is warranted to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the pharmacological effects of the trace elements present in Piper methysticum and to establish safe consumption guidelines for this plant extract.

Thesis Overview

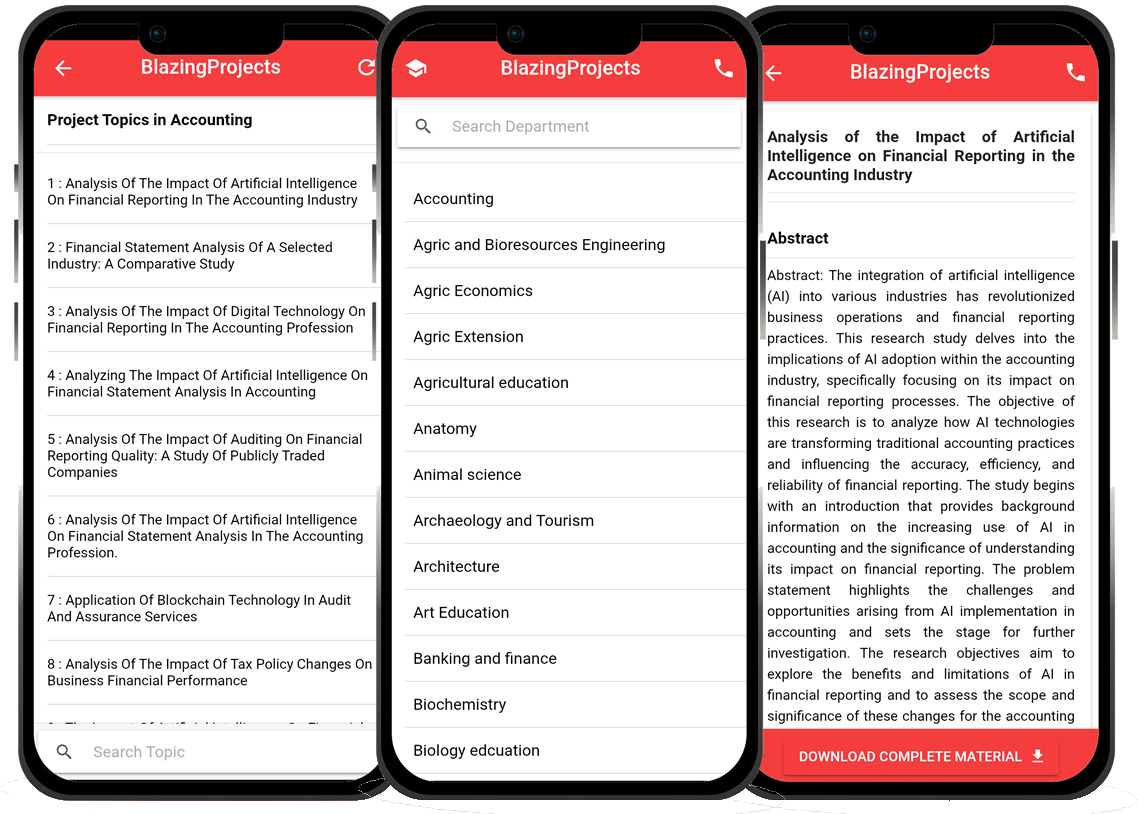

INTRODUCTION1.1 HerbsAn herb is a plant that is valued for flavor, scent, medicinal or other qualities other than its food value (John, 2000). They are used in cooking, as medicines, and for spiritual purposes. Herbs have a variety of uses including culinary and medicinal usage. General usage differs between culinary herbs and medicinal herbs (John, 2000). Herbs are -generally recognized as safe†by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA), at least at concentrations commonly found in foods (Kaefer et al, 2008). Medicinal plants continue to provide valuable therapeutic agents, both in modern medicine and in traditional system (Reaven, 1983). The leaves, roots, flowers, seeds, root bark, inner bark (cambium), berries and sometimes the pericarp or other portions of the plant might be considered in medicinal or spiritual use (John, 2000). In the medicinal uses, herbs (plants) contain phytochemicals that have effects on the body (John, 2000).Until the 20th century, (Sanusi et al, 2008) most medicinal remedies all over the world were obtained from plants. For example, purple forglove was found to be helpful in dropsy, the opium poppy for pain, cough, and diarrhea, and the cinchona bark for fever. With the emergence of chemical and pharmacological methods in the 20th century, it became possible to identify the active ingredients in the plants and study them. Furthermore, once the chemistry was understood, it was possible to synthesize related molecules with more desirable properties. According to (Sodimu et al, 2008), today, the two most effective and widely accepted drugs for the treatment of malaria today emerged through herbal traditional medicine viz: Quinine from the bark of the Peruvian cinchona tree and artemisinin from the Chinese antipyretic Artemisia annua L. Hence, throughout history, the medicinal benefits of herbs are quoted (John, 2000). There may be some effects when consumed in the small levels that typify culinary -spicingâ€, and some herbs are toxic in larger quantities. For instance, some types of herbal extract, such as the extract of St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum) or of awa (Piper methysticum) can be used for medical purposes to relieve depression and stress (John, 2000). However, (Milner et al, 2008), large amounts of these herbs may lead to toxic overload that may involve complications, some of a serious nature, and should be used with caution. One herb-like substance, called Shilajit, may actually help a lower blood glucose level which is especially important for those suffering from diabetes.In comparative terms, (Metuh, 1987) the western idea of medicine and the traditional African conception differ in scope. In the traditional sense, it refers to a wholistic view of well being, while in the western sense, it is strictly limited to bodily therapeutic purposes. Nze in his own comparative analysis of medicine underscores the peculiarity difference, which defines the traditional wholistic perception of medicine (Metuh, 1987).According to (John, 2000), modern pharmaceuticals had their origins in crude herbal medicines, and to this day, many drugs are still extracted as fractionate/isolate compounds from raw herbs and then purified to meet pharmaceutical standards. Some herbs are used not only for culinary and medicinal purposes, but also for psychoactive and/or recreational purposes; one such herb is cannabis (John, 2000).However, many herbs and their bioactive components are being investigated for potential disease prevention and treatment at concentrations which may exceed those commonly used in food preparation herbs (Milner et al, 2008). It is therefore imperative to identify any potential safety concerns associated with the use of various dosages which range from doses commonly used for culinary purposes to those used for medicinal purposes since there are often unclear boundaries between the various uses of herbs (Milner et al, 2008).Other uses of herbs other than medicinal uses are:Sacred uses:According to -Chinese herbal medicine†Herbs are used in many religions for example, myrrh (Commiphora myrrha) and frankincense (Boswellia spp) in Christianity, the Nine Herbs Charm in Anglo-Saxon paganism, the Neem tree (Azadirachta indica) by the Tamils, holy basil or tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum) in Hinduism, and many Rastafarians consider cannabis (Cannabis sp) to be a holy plant (John, 2000). Siberian Shamans also used herbs for spiritual purposes. Plants may be used to induce spiritual experiences, such as vision quests in some Native American cultures (John, 2000). The Cherokee Native Americans use sage and cedar for spiritual cleansing and smudging.Uses as pest control:Herbs are also known amongst gardeners to be useful for pest control. Mint, spearmint, peppermint, and pennyroyal are a few such herbs. These herbs when planted around a house’s foundation can help keep unwanted critters away such as flies, mice, ants, fleas, moth and tick amongst others. They are not known to be harmful or dangerous to children or pets, or any of the house’s fixtures (John, 2000).1.2 Objectives of studyPiper methysticum being a plant used for its medical and social purposes (Johnston et al, 2008), may have been of great benefits in human health due to its biochemical, pharmacological, and medical properties. This study, therefore, was undertaken to evaluate the trace - element composition of the leaf extract.REFERENCESBilia, A.R., Gallori, S. and Vincieri, F. (2002). Kava-kava and anxiety: growing knowledge about the efficacy and safety. Life Sciences 70: 2581-2597.Blumenthal, M. (1999). Herb market levels after five years of boom: 1999 sales in mainstream market up only 11% in first half of 1999 after 55% increase in 1998. HerbalGram 47: 64-65.Cagnacci, A., Volpe, A. and Arangino, S. (2003). Kava_/Kava administration reduces anxiety in perimenopausal women. Maturitas: The European Menopause Journal 44: 103 - 109Chikara, J. (2003). Study on the allelopathy of Kava (Piper methysticum L.). MSc Thesis. Miyazaki University, Japan, p. 70.Davis, R.I. and Brown, J.F. (1999). Kava (Piper methysticum) in the South Pacific: its importance, methods of cultivation, cultivars, diseases and pests. Canberra, Australia. p.13.Dentali, S.J. (1997). Herb Safety Review. Piper methysticum Forster f. (Piperaceae). Herb Research Foundation, Boulder, CO.Dragulla, K., Yoshida B, W. and Tanga, C. (2003). Piperidine alkaloids from Piper methysticum. Phytochemistry 63: 193-198Duve, R.N. (1976). Highlight of the chemistry and pharmacology of yaqona, Piper methysticum. Fiji Agriculture Journal 38: 81-84.El-Gamal, H.M., Shaker, H.K., Pollmann, K. and Seifert, K. (1995). Triterpenoid saponins from zygophyllum species. Phytochemistry 40 (4): 1233-1236.Ernst, E. (2002). Safety concerns about kava. Lancet 359: 1865.Fricchione, G. (2004). Clinical practice: Generalized anxiety disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 351: 675-682.Gow, P.J., Connelly, N.J., Hill, R.L., Crowley, P. and Angus, P.W. (2003). Fatal fulminant hepaticfailure induced by a natural therapy containing kava. Medical Journal of Australia 178: 442-443.Hamdy, A., Mansour, A., Al-Sayeda, A., Newairya, M.I. and Shewe Itac S.A. (2002). Biochemical study on the effects of some Egyptian herbs in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Toxicology 170: 221-228.Humberston, C.L., Akhtar, J. and Krenzelok, E.P. (2003). Acute hepatitis induced by kava kava. Journal of Toxicology/Clinical Toxicology 41: 109-113.Ibrahim, N.M. (1990). MSc Thesis. Institute of Graduate Studies and Research, Alexandria University pp.1-150.Ibrahim, R.F. (1998). MSc Thesis. Institute of Graduate Studies and Research, Alexandria University, pp. 1-124.Jaggy, H. and Achenbach, H. (1992). Cephradine A from Piper methysticum. Planta Med. 58: 111Johnston, E. and Rogers, H. (2006). Hawaiian ‘awa. Views of an ethnobotanical treasure (808) 323-3318.Kaefer, M.C. and Milner, J.A. (2008). The role of herbs and spices in cancer prevention. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 19: 347-361Kohli, R.K., Batish, D. and Singh, H.P. (1998). Allelopathy and its implications in agro-ecosystems. Journal of Crop Production 1: 169 - 202.Lebot, V. and Levesque, J. (1996). Genetic control of kavalactone chemotypes in Piper methysticum cultivars. Phytochemistry 43: 397-403.Lebot, V., Merlin, M. and Lindstrom, L. (1997). Kava, the Pacific elixir. Yale University Press, New Haven.Mansour, H.A. and New Airy, A.A. (2000). Amelioration of impaired renal function associated with diabetes by Balanites aegyptiaca fruits in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Journal of Medical Research Institute. 21 (4): 115-125.Metuh, E.I. (1987). Comparative Studies in African Traditional Religion. A division of Eternal Communication, Nigeria. P. 74Nelson, Scot. (2007). Plant Disease. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 123: 378 - 384Nerurkar, P.V., Dragull, K. and Tang, C.S. (2004). In vitro toxicity of kava alkaloid, pipermethystine, in HepG2 cells compareds to kavalactones. Toxicological Science 79: 106-111Pittler, M.H. and Edzard, E. (2000). Efficacy of kava extract for treating anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacol 20: 84 - 89.Reaven, G.M. (1983). Effect of age and diet on insulin secretion and insulin action in the rat. Journal of Medicine. 74: 69.Russmann, S., Lauterburg, B.H. and Helbling, A. (2001). Kava hepatotoxicity. Ann. Intern. Med. 35: 68-69.Schulze, J., Raasch, W. and Siegers, C.P. (2003). Toxicity of kava pyrones, drug safety and precautions-a case study. Phytomedicine. 10: 68-73Singh, Y.N. (1998). Blumenthal M. Kava, an overview. Herbalgram. 39: 33 - 55.Smith, R.M. (1983). Kava lactones in Piper methysticum from Fiji. Phytochemistry 22: 1055-1056.Sodimu, A.I., Faleyimu, O.I., Oloruntoba, M.M. and Sanusi, A.O. (2008). International Journal ofDevelopment in Medical Sciences. Vol.1.Stoller, R. (2000). Lebersch digungen unter Kava-Extrakten. Schweizerische Ärztezeitung 81: 1335-1336.Teschke, R., Gaus, W. and Lowe, D. (2003). Kava extracts: safety and risks including rare hepatotoxicity. Phytomedicine 10: 440-446.Teschke, R., Moreno, F. and Petrides, A.S. (1981). Hepatic microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (MEOS): respective roles of ethanol and carbohydrates for the enhanced activity after chronic alcohol consumption. Biochemical Pharmacology 30: 1745-1751.Teschke, R., Neuefeind, M., Nishimura, M. and Strohmeyer, G. (1983). Hepatic gamma glutamyl- transferase activity in fatty liver: comparison with other liver enzymes in man and rats. Gut 24:625-630.Teschke, R. and Petrides, A.S. (1982). Hepatic gamma-glutamyltransferase activity: its increase following chronic alcohol consumption and the role of carbohydrates. Biochemical Pharmacology 31: 3751-3756.Teschke, R. and Schwarzenbeck, A. (2009). Suspected hepatotoxicity by Cimicifuga racemosa rhizoma (black cohosh, root): critical analysis and structured causality assessment. Phytomedicine 16: 72-84.Teschke, R., Schwarzenböck, A. and Hennermann, K.H. (2008). Kava hepatotoxicity: a clinical survey and critical analysis of 26 suspected cases. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 20: 1182-1193.Weise, B., Wiese, M., Plotner, A. and Ruf, B.R. (2002). Toxic hepatitis after intake of kava-kava. Verdauungskrankheiten 4: 166-169.Whitton, P.A., Lau, A., Salisbury, A., Whitehouse, J. and Evans, C.S. (2003). Kava lactones and the kava-kava controversy. Phytochemistry 64: 673-679Xuan, T.D., Tsuzuki, E., Matsuo, M. and Khanh, T.D. (2003). Kava root (Piper methysticum L.) as a potential natural herbicide and fungicide. Crop Protection. 22: 873 - 881Zimmerman, H.J. (1999). Hepatotoxicity: The Adverse Effects of Drugs and Other Chemicals on the Liver, second edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA, Pp. 11-40.Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Research Thesis

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Thesis-to-Journal Publication

🎓 Undergraduate/Postgraduate Thesis

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Exploring the Role of Gut Microbiota in Human Health and Disease...

The project titled "Exploring the Role of Gut Microbiota in Human Health and Disease" aims to investigate the intricate relationship between gut micro...

Investigating the role of microRNAs in regulating gene expression in cancer cells....

The project "Investigating the role of microRNAs in regulating gene expression in cancer cells" aims to delve into the intricate mechanisms by which m...

Exploring the Role of Epigenetics in Cancer Development and Treatment...

The project titled "Exploring the Role of Epigenetics in Cancer Development and Treatment" focuses on investigating the intricate relationship between...

Analysis of the role of microRNAs in cancer progression...

The project titled "Analysis of the role of microRNAs in cancer progression" aims to investigate the intricate role of microRNAs in the progression of...

Investigating the role of microRNAs in regulating gene expression in cancer cells....

**Research Overview: Investigating the Role of microRNAs in Regulating Gene Expression in Cancer Cells** Cancer is a complex disease characterized by uncontrol...

Exploring the role of microRNAs in regulating gene expression in cancer cells...

The project titled "Exploring the role of microRNAs in regulating gene expression in cancer cells" aims to investigate the intricate mechanisms by whi...

Exploring the Role of MicroRNAs in Cancer Progression: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Po...

The project titled "Exploring the Role of MicroRNAs in Cancer Progression: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential" aims to investigate the intricate inv...

Exploring the role of microRNAs in cancer progression and potential therapeutic appl...

The project titled "Exploring the role of microRNAs in cancer progression and potential therapeutic applications" aims to investigate the intricate in...

Exploring the role of gut microbiota in metabolic diseases...

The project titled "Exploring the role of gut microbiota in metabolic diseases" aims to investigate the intricate relationship between gut microbiota ...