Ecowas effort in combating small and light arms proliferation in west africa: challenges and prospects

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Small Arms Proliferation2.2 Historical Context of Small Arms Proliferation in West Africa

2.3 Causes of Small Arms Proliferation

2.4 Impact of Small Arms Proliferation on West Africa

2.5 International Efforts in Combating Small Arms Proliferation

2.6 Regional Efforts in Combating Small Arms Proliferation

2.7 Challenges Faced in Combating Small Arms Proliferation

2.8 Prospects for Combating Small Arms Proliferation

2.9 Best Practices in Small Arms Control

2.10 Case Studies of Small Arms Proliferation in West Africa

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Design and Methodology3.2 Selection of Research Sample

3.3 Data Collection Methods

3.4 Data Analysis Techniques

3.5 Ethical Considerations

3.6 Reliability and Validity of Research

3.7 Limitations of Methodology

3.8 Research Tools and Instruments Used

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Overview of Research Findings4.2 Analysis of Small Arms Proliferation Trends

4.3 Regional Disparities in Small Arms Proliferation

4.4 Impact of Cultural Factors on Small Arms Proliferation

4.5 Policy Recommendations for Combating Small Arms Proliferation

4.6 Comparison of International and Regional Efforts

4.7 Evaluation of Effectiveness of Ecowas Efforts

4.8 Future Directions for Combating Small Arms Proliferation

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Findings5.2 Conclusion

5.3 Recommendations for Future Research

5.4 Implications for Policy and Practice

5.5 Contribution to Existing Knowledge

Project Abstract

AbstractThe proliferation of small and light arms in West Africa poses a significant security threat to the region, leading to instability, conflicts, and violence. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has made efforts to combat this issue through various initiatives and mechanisms. This research project aims to critically analyze ECOWAS' efforts in combating small and light arms proliferation in West Africa, focusing on the challenges faced and the prospects for success. The study will examine the various ECOWAS protocols, conventions, and action plans related to small arms control, such as the ECOWAS Convention on Small Arms and Light Weapons, their Ammunition and other Related Materials. By analyzing the legal framework and policy instruments put in place by ECOWAS, the research will provide insights into the strengths and weaknesses of these initiatives in addressing the proliferation of small arms in the region. Furthermore, the research will explore the operational challenges faced by ECOWAS in implementing these initiatives, including issues related to funding, coordination among member states, capacity building, and monitoring mechanisms. By interviewing key stakeholders, policymakers, and experts in the field, the study will gather qualitative data to understand the practical obstacles hindering ECOWAS' efforts in combating small arms proliferation. In addition, the research will assess the prospects for success in ECOWAS' initiatives to combat small arms proliferation in West Africa. By examining best practices and lessons learned from other regions, the study will provide recommendations for strengthening ECOWAS' approach to small arms control. This analysis will include suggestions for enhancing coordination among member states, improving information sharing, increasing public awareness, and enhancing monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. Overall, this research project will contribute to the existing literature on small arms proliferation in West Africa by providing a comprehensive analysis of ECOWAS' efforts in combating this issue. By identifying the challenges and prospects for success, the study aims to inform policymakers, practitioners, and researchers working on security and peacebuilding in the region.

Project Overview

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background to the Study

The

proliferation of small arms and light weapons is one of the major security

challenges currently facing Nigeria, Africa and indeed the world in general.

The trafficking and wide availability of these weapons fuel communal conflict,

political instability and pose a threat, not only to national security, but

also to sustainable development. The widespread proliferation of small arms is

contributing to alarming levels of armed crime, and militancy.

The increasing pace of violence across the

globe, with major occurrence in Africa, has brought about renewed focus on

small and light weapons control. It is estimated that there is an approximate

of 875 million small arms in circulation across the globe, including those

stockpiled and in private procession, produced by over 1000 companies and

generating trade excess of US$8.5 billion (Karp, 2007). Out of this ominous

volume, governments and state militaries possess 200 million while 26 million

weapons are within the control of the law enforcement agencies. Similarly,

Chelule (2014) noted that there are about half a billion military small arms

around the world; each year between 300,000 to half a million people around the

world are killed by these weapons and every minute someone is killed by a gun;

90% of civilians are casualties by small arms because the civilians get access

to purchase more than 80% of the arms produced in the world. To establish the

extent of this threat in Africa, Bah (2004) asserts that out of an approximate

of 500 million illicit weapons in circulation worldwide, an estimate of 100

million are in Sub-Saharan Africa with eight to ten million concentrated in the

West African sub-region alone. This portentoustrend

further reveals that Africa needs strategic intervention.

Small arms proliferation has been particularly devastating in

Africa where machine guns, rifles, grenades, pistols and other small arms have

killed and displaced many civilians across the continent (Allison, 2006). The

result of this rapid expansion of weapons according to Allison (2006) is that

the weapons, their parts and ammunition are more easily diverted from their

intended destination. Consequently, countries with fewer and less strict gun

regulations become the destination points. War-torn or post-conflict nations

which are common in Africa portend a profitable market for the sale of Small

Arms and Light Weapons (SALW). The guns have thus far fostered instability in

the West African region, worsened the security of the region, weakened the

power of the government and provided a motivation for poverty to thrive.

At the national level, Nigeria continues to rely onthe National

Firearms Act of 1959 as the legal instrument governing small arms possession,

manufacture and the use in the country as amended even though the Robbery and

Firearms (Special Provisions) Decree No.5 was promulgated in 1984 and later the

Robbery and Firearms (Special Provisions) Act. In July 2000, the Nigerian

government proposed and established a National Committee on the Proliferation

and Illicit Trafficking in Small Arms and Light Weapons the purpose of which

was to determine the sourcing illegal small arms and collect information on

small arms proliferation in Nigeria. In May 2001, the government established a

second committee aimed at implementing the 1998 ECOWAS Moratorium. These two

committees were later merged into a single committee. The committee has

accomplished little due to lack of political will, financial support, technical

expertise, and institutional capacity. Consequently, there were renewed efforts

in 2007 to revive the activities of the Committee and legislation is being

written to convert the Committee into a national commission. It requested

support from the ECOWAS Small Arms Programme to conduct the survey and to undertake

other activities in support of the implementation of the 2006 ECOWAS Convention

(Hazenand Horner, 2007). Inaugurated in 2001, the NATCOM is responsible for the

registration and control of SALW, and granting of permits for exemptionsunder

the ECOWAS Moratorium (Chuma-Okoro, 2011).

Despite these national-efforts, the rate of accumulation ofSALW is

increasing and becoming endemic as various forms of violence and casualties are

in the recent times recorded in the country. There is lack of capacity and

strong legal or effective institutional frameworks to regulate SALW and combat

the phenomenon of SALW proliferation in Nigeria, particularly Northern part of

Nigeria (Chuma-Okoro, 2011). More fundamentally, the Nigeria is yet to deal

with the demand factors of SALW proliferation preferring to dwell on the

symptoms rather than the root causes. The demand factors are the root causes of

SALW proliferation, because if there is no demand, there will not be supply. Consequently,

Nigeria now features prominently in the three-spot cline of transnational

organised trafficking of SALWs in West Africa: origin, transit route and

destination. Weapons in circulation in Nigeria come from local fabrication,

residue of guns used during the civil war, thefts from government armouries,

smuggling, dishonest government-accredited importers, ethnic militias,

insurgents from neighbouring countries and some multinational oilcorporations

operating in the oil-rich but crisis-plagued Niger Delta. Whenand where these

SALWs are deployed, human security has been the main victim.

These were the motivations

for the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Convention of Small

arms and Light Weapons in 2006. The highlights of the Convention include the a ban on international

small arms transfers (except those for legitimate self-defence and security

needs, or for peace support operations); a ban on transfers of small arms to

non-state actors that are not authorized by the importing member state;

procedures for shared information; stringent regulatory scheme for anyone

wishing to possess small arms and strong management standards to ensure the

security of weapons stockpiles.

It is in consonance with the highlight of the 2006 SALW Convention

and other subsequent attempt of ECOWAS to tackle the issues of gun control that

this study attempts to examine the challenges of ECOWAS in combating Small and

Light Arms in Africa.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

The dimensions and persistence of conflicts in West Africa has

created a favourable outlet for the sale of arms and other light weapons.

Chiekh (2005) noted that these conflicts

have had the combined effect of sucking in millions of illicit small arms, making

the Mano River Basin (comprising Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia and, by

extension, Côte d’Ivoire) an attractive and profitable theatre for illicit arms

merchants, mercenaries and other non-state actors. These unstable conditions make it difficult to

regulate arms sales and movements. More so, the dealings in Small Arms and

Light Weapons (SALWs) have been a source of income for countries who are

engaged in the production of guns. Apart from the direct sales of guns and

light weapons, weapons are traded with West Africans for natural resources such

as rubber, timber and, most importantly, diamonds

(Chiekh, 2005). This barter system has made the running of SALW beneficial to

both parties.

In West Africa, the uneven implementation of

regional agreements leaves loopholes that arms traffickers can utilize for

their nefarious trade. These traffickers are usually quick to adopt trade

routes where national controls are weak, and often take advantage of

insufficient cooperation between border control authorities or differences in

national regulation. These trends have necessitated the quest for a framework

for the implementation of the ECOWAS convention and the need for a broad based

inter-sectoral platform and collaboration between government and agencies, and

local communities.So far, the ECOWAS convention is still undergoing

harmonization with local arms law in the various national parliaments of member

states.

About 350 million of the 500 million Small

Arms and Light Weapons (SALWs) in West Africa are in Nigeria. This is a

whopping 70 per cent of the West African sub-region’s SALWs, 90 per cent of

which are in the hands of non-state actors. Yet the situation only promises to

grow worse with the influx of weapons from the residue of the conflicts in

Libya and Mali (This Day, 2016). What this has revealed clearly is that there

is a growing market for SALWs in the country and government ought to intervene

more decisively to stem the ugly tide. The insurgency in the North-East, the

resurgence of militancy in the Niger Delta, the menace of herdsmen in the

North-Central and the rising wave of violent crimes, including armed robbery

and kidnappings, particularly in the South-East and the South-West of the

country are directly linked to the upsurge in SALWs even as they demonstrate

the concrete negative impact on national efforts at integration and

development.

To deal with these challenges, government

needs to key into the ECOWAS Convention on Small Arms and Light Weapons. In

light of this, it is pertinent to note that while Nigeria is a signatory to the

ECOWAS protocols, the National Assembly is yet to pass the bill concerning the

establishment of the National Commission against the Proliferation of Small

Arms and Light Weapons. Indeed, Nigeria is the only West African country that

does not have the commission that is saddled with the responsibility of

tracking the spread of SALWs. In like manner, the archaic 1959 Firearms Act

that regulates the use of firearms in the country is yet to be amended by the

federal legislature.

These challenges as it applies to states in

West Africa have not only hampered the economic development of the individual

states but that of the region also, putting both lives and property in danger. The proliferation of these small arms and the

new emergent trend in violence in the region put to question the efficacy and general

commitment of ECOWAS to combating this menace (Bashir, 2014). The research is therefore an attempt to

critically evaluate the challenges and prospects of ECOWAS in combating small

and light arms proliferation in the region vis-à-vis the effects of small and

light weapon proliferation in West Africa.

1.3 Objective of the Study

The main objective of the study is to investigate the efforts and

challenges of ECOWAS in its bid to control the proliferation of Small and Light

Arms in the West African region. The specific objectives are to:

- trace the flow and distribution of small and

light arms in West Africa; - assess the instruments used by Ecowas in

combating Small and Light Arms in the West Africa;

- examine Ecowas border control

methodologies and its protocol on free movement of people and goods in

light of the proliferation of small and light arms in West Africa; - ascertain the extent to which Nigeria has

implemented theEcowas Convention on Small Arms and Light Weapons and - probe the effects of domestic laws on the

general objectives of Ecowas Small Arms Control Programme vis-à-vis the extent

to which the Nigerian Fire Arms law has curbed the proliferation of small

and light arms in Nigeria.

1.4 Research Questions

The following research questions would be

addressed in the course of the research, serving as a guideline to the

attainment of the research objectives:

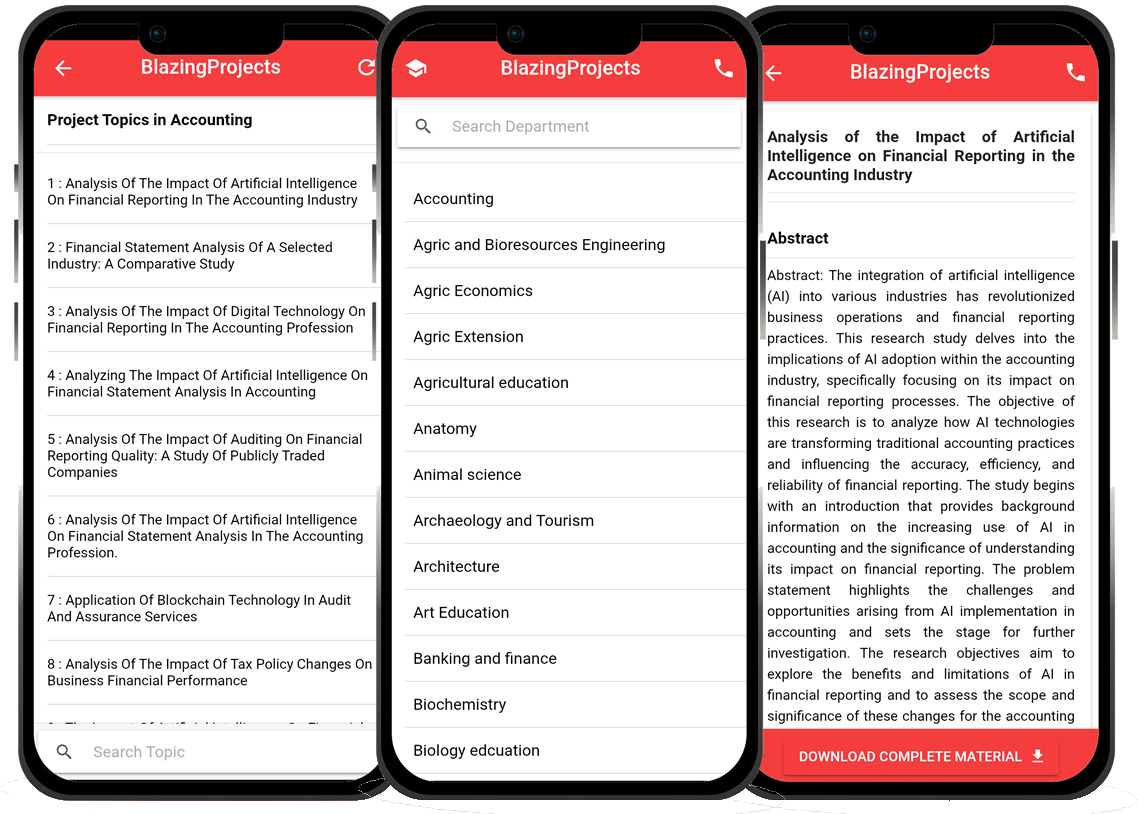

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation in Democratic Societies...

The project topic "The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation in Democratic Societies" delves into the intersection of social media and pol...

The Impact of Social Media on Political Campaigns: A Comparative Analysis...

The project titled "The Impact of Social Media on Political Campaigns: A Comparative Analysis" aims to investigate the role and influence of social me...

The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation and Engagement...

The project topic, "The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation and Engagement," delves into the dynamic relationship between social media p...

The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation in Democracies...

The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation in Democracies Overview: Social media has become an integral part of modern society, revolutionizing the...

The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation and Engagement in Democracies...

The project topic, "The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation and Engagement in Democracies," delves into the transformative role of socia...

An Analysis of the Impact of Social Media on Political Campaigns...

The project titled "An Analysis of the Impact of Social Media on Political Campaigns" aims to investigate the profound influence of social media platf...

The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation in Democracies...

The project topic, "The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation in Democracies," focuses on examining the relationship between social media ...

Analyzing the Impact of Social Media on Political Campaigns...

The project aims to investigate the profound influence of social media on political campaigns in contemporary society. As the world becomes increasingly interco...

The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation and Engagement...

The project topic, "The Impact of Social Media on Political Participation and Engagement," delves into the intricate relationship between social media...