Flammability studies of some fire tolerant trees of south-east, nigeria

Table Of Contents

<p> </p><p>Title Page – – – – – – – – – i<br>Approval Page – – – – – – – ii<br>Dedication – – – – – – – – – iii<br>Acknowledgements – – – – – – – iv<br>Abstract – – – – – – – – – v<br>Table of Contents – – – – – – – vi</p><p>

Chapter 1

<br>INTRODUCTION – – – – – – 1<br>1.1 Background – – – – – – – 1<br>1.2 Fires: A Historical Perspective- – – – – 2<br>Chapter 2

<br>LITERATURE REVIEW – – – – – – 8<br>2.1 Pyrolysis- – – – – – – – 8<br>2.2 Combustion – – – – – – – 14<br>2.3 Pyrolysis and Combustion – – – – – 20<br>2.4 Mechanism of Flame Retardancy – – – – 21<br>2.5 Fire Extinguishment- – – – –<br>2.6 The Burning Cycle – – – – – – 22<br>2.7 Tree Characterization – – – – – – 24<br>2.8 Fire Tolerance – – – – – – – 40<br>2.9 Factors that contribute to fire tolerance in Timbers- – 41<br>2.10 Flammability Testing – – – – – – 43<br>2.11 Scope of Work – – – – – – – 48<br>2.12 Objectives – – – – – – – – 48</p><p>Chapter 3

<br>8</p><p>EXPERIMENTAL – – – – – – 49<br>3.1 Materials and Methods – – – – – 49<br>3.2 Research Methodology – – – – – 54<br>3.3 Characteristics of the Samples – – – – 56</p><p>Chapter 4

<br>RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS – – – – – – 61<br>4.1 Oral Interview – – – – – – – 61<br>4.2 Effect of Density – – – – – – – 61<br>4.3 Effect of Moisture Content – – – – – 67<br>4.4 Burning Behaviours – – – – – – 67<br>4.5 Flame Propagation Rate – – – – – 68<br>4.6 After Glow Time – – – – – – – 70<br>4.7 Ignition Time – – – – – – – 73<br>4.8 Flame Duration – – – – – – – 75<br>4.9 Ash Formation and Glowing Combustion – – 76<br>4.10 Limiting Oxygen Index – – – – – – 79<br>4.11 Conclusions- – – – – – – – 80<br>REFERENCES – – – – – – – – 81<br>APPENDICES – – – – – – – – – 91</p> <br><p></p>Project Abstract

Bush fire is a common hazard in South Eastern Nigeria as in other parts

of the country during the harmattan. Every year, thousands of hectares

of forests as well as suburban lands are severely burnt. These forest

fires have been catastrophic, destroying large areas of tropical rain

forests. However, some trees in these forests have proven to be fire

resistant. These tree species were identified by local people.

Flammability studies of fifteen of these fire tolerant trees of South

Eastern region of the country were carried out with a view to

encouraging their use in afforestation. The flame characteristics, viz.,

ignition time, flame propagation rate, after glow time, flame duration,

char formation, and limiting oxygen indices of these tree species were

carried out. In addition, physical properties such as densities and

moisture contents were evaluated in order to determine their effects on

their burning parameters. The values for these parameters vary among

the selected tree species. Density in particular, related to the ignition

and flame spread behaviours, although, for the denser hard woods above 0.50g/cm3 and this dependence is less straight forward. Attempts

were made to explain these observations on the basis of thermal

conductivities, cellular structures, and presence of special flame resistant

pyrolysates at flaming temperature.

Project Overview

INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND

The use of dry natural wood in building, construction and for furniture is

well established[1]. Wood is generally regarded as possessing a high

degree of combustibility when sufficient quantity of heat energy is

applied[1]. It can be ignited by a variety of fire sources and once ignited

the flame may spread rapidly across the surface with slower progress

through the bulk until the fire becomes general. This is the cause of

significant numbers of injuries and fatalities in fires reported yearly by

various countries[2-4]. Because of this, and within the African continent,

the phenomenon of combustion in terms of pyrolysis and flammability

has been the subject of extensive studies directed towards three primary

interests: building and contents, forest and grassland fires[1].

In its broadest sense, the performance of wood in fires can be described

in terms of three distinct burning phenomena namely ignition, flamming

and glowing, which present different potential hazards, and should be

approached in different ways. In the past, many studies of the thermal

decomposition of cellulose or lignocelluose have been reported [5-10].

The ignition properties of cellulose materials have been reviewed and

discussed in various publications [11-13]. Nonetheless, it is surprising

that little literature is available on the thermal characteristics of tropical

timbers. There is no doubt that in the near future, the wood resources of

the temperate zones cannot support an increasing wood demand. The

vast resources of the tropical rainforests should therefore become of

10

decisive interest for future timber and forest planning, renewal and

development.

1.2 FIRES: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Fire or flame, simply put, is a region of hot gases raised to

incandescence [14]. This definition implies that the burning material,

which are in most cases polymers, (compounds having very high molar

mass) such as cellulose, plastics, rubbers, etc, must be able to supply

gases that burn.

Man began to emerge from the cave when he learnt to use fire. The

acquisition of the skill to use and control fire and its products is no

doubt, one of the most fundamental inventions. The eventual spread of

man across the Earth’s surface is directly linked with his ability to make

and control fire. This is so because, otherwise, man would have been

restricted to live only in areas with a hospitable warm climate. The

importance of fire in the human experience is attested by the fact that it

has been observed in every human culture of the recent past [14].

It is reasonable to state that the advent of the match in 1680 when

Robert Boyle used white phosphorus to ignite sulphur-tipped wood

splints was a huge success for fire making[13]. An improvement on this

came in 1827 when John Walker developed a match which was ignited

by drawing its head between layers of sand paper (the friction match)

[13]. Finally the safety match, these days a common household item,

was perfected by the Swedes in 1855[13].

Fire is a natural environmental phenomenon and has been an integral

part of our eco-system for millennium. The population and development

of North America has repeatedly brought humans into contacts with fire

11

in all manner of circumstances including wildland fires. Over the past

400 years [15], Americans as a society have grown to gear all forms of

fire and have sought ways to suppress it as completely as possible.

Wildland fires, however, pose unique challenges to the fire service and

require vastly different approaches to its prevention, mitigation, and

suppression. As more people choose to leave the cities and build their

homes in the “wildland/urban” interface, it is critical that these concerns

are addressed.

Natural wildland fires are generally caused by lightning, which strikes the

earth an average of 100 times each second or 3 billion times every

year[16] and has caused some of the most notable wildland fires in the

United States (e.g. Yellowstone in 1988). Other natural causes include

sparks from falling rocks and volcanic activity.

Human activity, however, is the primary cause of wildland fires. Some

of these fires are intentional, such as those that were used by Native

American as signals or to drive game, those set by forestry experts, or

those set by arsonists. Others, however, have been accidental, caused

by carelessness or inattention by campers, hikers, or others traveling

through wildlands [17]. Table 1 illustrates the 10-year average of fires

by their cause and average burned.

Table 1: 10-year average of Wildland fire causes (1788-97) [18]. Human cause Lightning cause Number of fires 102,694 13,879 Percent of fires 88 12 Acres burned 1,942,106 2,110,810 Percent of acreage 48 52

The three primary classes of wildland fires are surface, crown, and

ground. These classifications depend on the types of fuel involved and

intensity of a fire. Surface fires typically burn rapidly at a low intensity

12

and consume light fuels while presenting little danger to mature trees

and root systems. Crown fires generally result from ground fires and

occur in the upper section of trees, which can cause embers and

branches to fall and spread the fire. Ground fires are the most

infrequent type of fire and are very intense blazes that destroy all

vegetation and organic matter, leaving only bare earth [19]. Large fires

actually create their own winds and weather, increasing the flow of

oxygen and “feeding” the fire [18].

There is a dichotomy associated with wildland fires; they threaten

resources we value, yet they are an essential part of most ecosystems.

Several plant species even depend on it to reproduce. Some pinecones

require fire to melt away a resinous coating before the seeds inside are

released, while others produce seeds that lie dormant in the seedbed

and germinate only after exposure to the heat from a fire [16].

Recovery from a wild land fire begins even before the last of the flames

are extinguished. After a wild land fire, essential nutrients are released

back into earth through the burning of mature plants and organic litter

[16]. Additionally, wildland creatures have learned to adapt to fires.

Small animals generally hide in burrows, birds fly away, larger mammals

run away and fish are protected by the water in which they live. These

animals are capable of adjusting to radical changes in their habitat,

which endure until the next fire in that area [17].

Erosion is a critical concern as heavy rains in the wake of wildland fire

can cause landslides or debris flows, and run off can have damaging

effects on water sources. In some areas, if the fire was intense enough,

the soil actually becomes hydrophobic and cannot absorb water,

exacerbating the situation [19].

13

The first wildland fire control program was established in 1885 in the

Adirondacks Reserve in New York. By the following year, a program

was established in Yellowstone Park. Both were modeled on practices in

use in Germany, considered the model for forest management, which

were to extinguish all fires regardless of severity. In 1910, these policies

were reexamined after catastrophic blazes burned 5 million acres and

killed 79 fire-fighters [15]. As a result, the US Forest Service (USFS)

“declared war” on fires and launched an aggressive campaign on fire

prevention and control.

In 1926, after questions arose regarding the merits of light burning, the

USFS adopted a policy that would allow areas of 10 acres or less to

burn, but required the suppression of all fires over 10 acres. The

Tillamook burn in 1933 destroyed 3 million acres of virgin timberland in

the Northwest [15]. In its wake, the USFS reverted to an even more

stringent “ no burn” policy and mandated that all fires were to be

extinguished during the first duty shift after its discovery or by 10 am the

following day. This policy remained in effect and was reexamined in

1971 when the USFS changed its policies to allow some lightning fires to

burn as natural prescribed fires.

In 1978, the USFS again revised the policy, this time excluding the 10

am objective. The emphasis was shifted to managing fire suppression

costs so that they are consistent with land and resources management

strategies. By 1988, changes in Policy by the USFS and National Park

Services allowed many natural fires to burn on federal wildland [20].

14

Despite policy and myriad suppression efforts, wildland fire has been a

continued problem in America’s forests. Table 2 illustrates some

historically significant wildland fires.

Table 2: Selected Historically Significant Wildland Fires [18]

Date Name Location Acres Significance Oct 1871 Peshitog Wisconsin/Michagan 3,780,000 1,500 fatalities in Wisconsin Sep 1894 Hinckley Minnesota Undetermined 418 lives lost Sep 1894 Wisconsin Wisconsin Several million Undertermined; some lives lost Aug 1910 Great Idaho Idaho/Montana 3,000,000 85 fatalities 1949 Mann Gulch Montana 4,339 13 smokejumpers killed Sep 1970 Laguna California 175,435 382 structures destroyed 1987 Siege of ‘87 California 640,000 Valuable timber lost on the Klamath and Stanislaus National Forests 1988 Yellowstone Montana/Idaho 1,585,000 Large acreage Oct 1991 Oakland Hills California 1,500 25 lives lost and 2,900 structures destroyed Jul 1994 South Canyon Colorado 1,856 14 firefighters fatalities 1998 Volusia complex Florida 111,130 Thousands of people evacuated from several countries 1998 Flagler/St. John Florida 94,656 Forced the evacuation of thousands of residents May 2000 Cerro grande New Mexico 47,650 Originally a prescribed fire; 235 structures destroyed; damaged Los Alamos National Laboratory

Today, fire suppression agencies throughout the country are increasingly

challenged by wildland fires that affect structures located in areas that

are essentially wildland. The question what to do with the urban/wildland

interface has become one of the most controversial in the fire service.

Some have argued that it is not appropriate for publicly funded fire

suppression personnel to be dedicated to protecting homes built in this

dangerous area when they can be better utilized elsewhere. Others,

15

however, claim that one has the right to build home anywhere he or she

wants, in spite of the possible ramifications of such an action. Another

controversy is over how to thin the forests and lighten their fuel load.

Some argue the emphasis should be on prescribed burning while others

are proponents of mechanical thinning (cutting trees strategically) [15].

Given the political, ecological and economic implications of any decision

affecting residents and homes in the interface, these debates are likely

to continue for years to come.

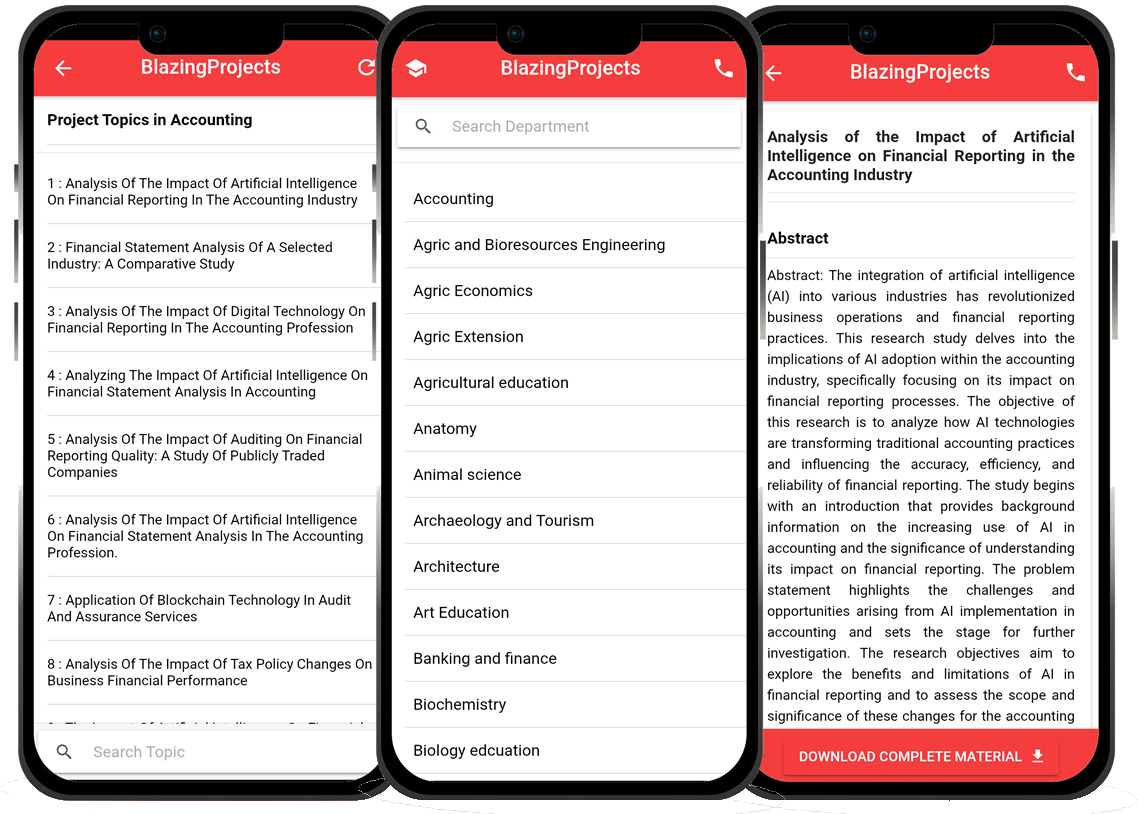

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Development of Advanced Catalysts for Green Chemistry Applications in Industrial Pro...

The project titled "Development of Advanced Catalysts for Green Chemistry Applications in Industrial Processes" aims to address the growing need for s...

Synthesis and Characterization of Green Catalysts for Sustainable Chemical Processes...

The project topic, "Synthesis and Characterization of Green Catalysts for Sustainable Chemical Processes in Industrial Applications," focuses on the d...

Development of Novel Catalysts for Green Chemistry Applications in Industrial Proces...

The project titled "Development of Novel Catalysts for Green Chemistry Applications in Industrial Processes" aims to address the growing need for sust...

Synthesis and Characterization of Sustainable Biodegradable Polymers for Packaging A...

The project on "Synthesis and Characterization of Sustainable Biodegradable Polymers for Packaging Applications in the Food Industry" aims to address ...

Green Chemistry Approaches for Sustainable Industrial Processes...

The project topic, "Green Chemistry Approaches for Sustainable Industrial Processes," focuses on the application of green chemistry principles in indu...

Development of Sustainable Processes for the Production of Green Fuels...

The project "Development of Sustainable Processes for the Production of Green Fuels" focuses on addressing the pressing need for renewable and environ...

Application of Green Chemistry Principles in Industrial Processes...

The project topic "Application of Green Chemistry Principles in Industrial Processes" focuses on the utilization of green chemistry principles to enha...

Investigation of green chemistry approaches for the sustainable production of specia...

The project titled "Investigation of green chemistry approaches for the sustainable production of specialty chemicals in the industrial sector" aims t...

Development of Sustainable Methods for Waste Water Treatment in Industrial Processes...

The project topic, "Development of Sustainable Methods for Waste Water Treatment in Industrial Processes," focuses on addressing the critical need for...