The Longitudinal Association Between Body Image Dissatisfaction, Social Anxiety, and Fear of Negative Evaluation in Adolescents

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction 1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Body Image Dissatisfaction 2.2 Social Anxiety

2.3 Fear of Negative Evaluation

2.4 Adolescents and Body Image

2.5 Psychological Impact of Social Anxiety

2.6 Fear of Negative Evaluation in Adolescents

2.7 The Relationship Between Body Image Dissatisfaction and Social Anxiety

2.8 The Connection Between Social Anxiety and Fear of Negative Evaluation

2.9 Body Image Dissatisfaction, Social Anxiety, and Fear of Negative Evaluation: Previous Research

2.10 Gaps in Current Literature

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Methodology Overview 3.2 Research Design

3.3 Population and Sample

3.4 Data Collection Methods

3.5 Data Analysis Techniques

3.6 Ethical Considerations

3.7 Validity and Reliability

3.8 Limitations of the Methodology

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Data Analysis and Results 4.2 Descriptive Statistics

4.3 Inferential Statistics

4.4 Relationship Between Body Image Dissatisfaction and Social Anxiety

4.5 Influence of Fear of Negative Evaluation on Social Anxiety

4.6 Comparison of Findings with Existing Literature

4.7 Discussion of Key Findings

4.8 Implications for Theory and Practice

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Conclusion 5.2 Summary of Findings

5.3 Contribution to Knowledge

5.4 Recommendations for Future Research

5.5 Practical Implications

Project Abstract

Abstract

Adolescents with body image dissatisfaction experience more anxiety than their peers who are more satisfied with their body. This is problematic given that adolescents who experience these concerns have a greater likelihood of later developing other mental health disorders and have more disordered eating cognitions and behaviour. For this reason, I investigated how body image dissatisfaction, social anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation were related to one another. Participants included 527 adolescents (301 girls; aged 15 to 19 years; 83.1% White) who were accessed annually over 4 years (Grade 10 to one-year post high school) using the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, the Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation scale-II, and validated questions to assess body image dissatisfaction. A developmental cascade model was used to examine direct and indirect effects between the study variables. Results indicated two significant indirect paths; body image dissatisfaction to social anxiety via fear of negative evaluation and body image dissatisfaction to fear of negative evaluation via social anxiety. Direct effects included a reciprocal positive association between body image dissatisfaction and social anxiety in mid-adolescence and a reciprocal positive association between social anxiety and fear of negative evaluation across adolescence. Lastly, there was a positive association from body image dissatisfaction to fear of negative evaluation across adolescence. These results suggest that adolescents with low body image dissatisfaction are likely to experience greater fear and anxiety regarding social interaction. This study emphasizes the need to target adolescents with body image intervention programs to reduce the experience of psychopathology

Project Overview

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND STUDY

Anxiety disorders include “excessive fear and anxiety and related behavioral disturbances” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 189). Fear encompasses the emotional response to a threat that is either present or absent, whereas anxiety is the concern over a threat occurring in the future (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). With anxiety disorders, individuals develop a preconscious attentional bias toward a stimulus which is deemed threatening (Craske et al., 2009). Consequently, individuals have an elevated sensitivity to the feared object(s) (Craske et al., 2009). Anxiety can be present in children. For example, a child may exhibit separation anxiety when their parent leaves the room (Rynn, Vidair, & Blackford, 2012). Of all the mental disorders, anxiety disorders are the most frequent class of psychiatric disorders that children and adolescents are diagnosed with (Rynn et al., 2012). Anxiety is a global concern with one in 14 adults experiencing an anxiety disorder at any given time (Baxter, Scott, Vos, & Whiteford, 2013). The prevalence of anxiety disorders in youth is also high, with an estimation that 204,400 Canadian youth between the ages of 4- and 17-years affected (prevalence of 3.8%; Waddell, Shepherd, Schwartz, & Barican, 2014). Childhood and adolescence is a critical developmental period where youth are at risk of developing symptoms of anxiety which could range anywhere from mild symptoms to diagnosable anxiety disorders (Beesdo, Knappe, & Pine, 2009). These findings are disconcerting given that youth who develop anxiety disorders are more likely to be affected by subsequent anxiety disorders (Beesdo et al., 2009; Clark, Smith, Neighbors, Skerlec, & Randall, 1994, Kashani & Orvaschel, 1990) and other mental illnesses throughout their life (Beesdo et al., 2009). Specifically, in children aged 8- through 17-years, generalized anxiety disorder was found to be the most common psychiatric disorder (Kashani & Orvaschel, 1990). Anxiety regarding social fears, interpersonal concerns, and personal adequacy were highest in late adolescence (Kashani & Orvaschel, 1990). As well, it is more likely for older adolescents to experience social anxiety compared to younger adolescents (Burstein et al., 2011), making the sample of the present study—mid to late adolescence—particularly relevant. There are a variety of negative outcomes that arise from youth experiencing a mental health problem. Anxiety negatively impacts interpersonal and intrapersonal behaviour in adolescents (Kashani & Orvaschel, 1990). Kashani and Orvaschel (1990) found that anxious 17- year-olds (compared to non-anxious 17-year-olds) had worse social relationships and more behavioural concerns, mood problems, somatic complaints, and school difficulties. Having more anxiety symptoms is related to poorer health-related quality of life (Raknes et al., 2017). Given the decreased quality of life that accompanies anxiety symptoms, there is a need to improve mental health interventions and implement prevention initiatives that target anxious adolescents. Anxiety disorders are differentiated from one another based on the situation or object that contributes to the anxious or fearful response. A few examples of anxiety disorders include separation anxiety (fear or anxiety experienced when separated from one’s attachment figure), specific phobia (fear or anxiety toward a particular object or situation), and of particular relevance to the present study, social anxiety (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). With social anxiety disorder, the fear or anxiety experienced by an individual is related to social situations or interpersonal interaction. The cognitive component of this disorder often involves worry over being embarrassed, humiliated, or rejected by others (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The presentation of social anxiety, thus, has a strong social evaluative component Social anxiety exists on a spectrum, such that individuals can experience symptoms of social anxiety without meeting the criteria for a formal diagnosis for social anxiety disorder. The 12-month prevalence rates for children and adolescents for social anxiety disorder are comparable to adults which is around 7% (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Stein, Walker, and Forde (1994) found that 33.3% of Canadian adults were “much more nervous than other people” in at least one social situation, although these participants did not necessarily have social anxiety disorder (p. 410). This suggests that it is relatively common to experience anxiety in social situations; however, it is much less common to have social anxiety disorder. It is well known that the diagnosis of social anxiety results in a greater risk of other mental health disorders and overall life impairments; however, even individuals with subclinical expressions of social anxiety have been found to experience these impairments (Fehm, Beesdo, Jacobi, & Fiedler, 2008). The participants in the present study were assessed in terms of social anxiety symptoms and were not required to meet the criteria for social anxiety disorder to be considered. Regarding body image, body image dissatisfaction has been found to be positively related to anxiety (e.g., Cruz-Sáez, Pascual, Salaberria, & Echeburúa, 2015; Dooley, Fitzgerald, & Giollabhui, 2015; Duchesne et al., 2017). In one study, anxious 17-year-olds had a worse selfconcept than same-aged adolescents without anxiety (Kashani & Orvaschel, 1990). Thus, it appears that those with anxiety are more likely to experience body image dissatisfaction. Body image is defined as “one’s thoughts, perceptions, and attitudes about their physical appearance” which includes what one believes about their appearance and how one thinks and feels about their body (Body Image & Eating Disorders, 2018). Body dissatisfaction usually has negative impacts on a person’s life. For example, those with body image dissatisfaction have been found to experience distress and/or attempt to alter their appearance (Cash, 1996). Neumark-Sztainer, Paxton, Hannan, Haines, and Story (2006) found that adolescent boys and girls were more likely to diet and engage in unhealthy weight control behaviour if they were dissatisfied with their body. Men and women in late adulthood with body image dissatisfaction were more likely to experience anxiety and depression, and middle-aged men were more likely to have problematic social and sexual functioning if they were dissatisfied with their body (Davison & McCabe, 2005). Conversely, individuals who were satisfied with their body image were less likely to experience anxiety and to have problematic internet use, and were more likely to have good selfesteem (Cash, 1996). Specific to youth, body image dissatisfaction has been found to be related to a variety of psychological well-being factors including more distress, depression, and anxiety, and worse self-esteem and self-concept. In their review of the literature on body image in boys, Cohane and Pope (2001) found that body dissatisfaction in boys (under 18 years) was often associated with distress (e.g., impaired self-concept and self-esteem). Similarly, Kostanski and Gullone (1998) found that body image dissatisfaction was negatively correlated with self-esteem in adolescents between the ages of 12 and 18. Body image dissatisfaction was also related to depression and anxiety, such that the more body image dissatisfaction that an adolescent reported, the more anxiety and depression they were likely to have (Duchesne et al., 2017; Kostanski & Gullone, 1998). Thus, the more concerned adolescents are about their body image, the less likely they are to have good self-esteem and the more likely they are to experience psychological distress (i.e., depression and anxiety). Given that body image dissatisfaction is related to various psychological disturbances in youth, adolescence is a prime time to investigate this variable. With an understanding that body image dissatisfaction tends to be relatively consistent throughout adulthood (Davison & McCabe, 2005), it is important that adolescent body image is acknowledged rather than waiting for these concerns to negatively impact individuals throughout their life. Specifically concerning anxiety, more body image dissatisfaction has been shown to be associated with more anxiety (e.g., Di Blasi et al., 2015; Duchesne et al., 2017). Halliwell and Dittmar (2003) found that women (mean age of 31 years) who were exposed to thin models in the media had more body-focused anxiety compared to those who were exposed to average-sized models or no models. This suggests that body image in the media impacts anxiety. Given that we are regularly surrounded by advertising in various forms, being exposed to thin models is often unavoidable making it likely for anxiety to be experienced. When individuals experience anxiety about their health they were more likely to engage in body checking (Hadjistavropoulos & Lawrence, 2007), which provides further support to the argument that anxiety and body image are linked. It is possible that those who experience body image dissatisfaction are more vigilant of their body, leading them to experience anxiety in social situations since they are not feeling confident with their body. Gaining a better understanding of the relation between body image dissatisfaction and anxiety in adolescents is important for informing, and consequently improving, the mental health of adolescents. A better understanding can come from investigating the potential impact that certain variables have on body image dissatisfaction and social anxiety. For instance, children who were rejected by their peers have been found to experience increased negative affect and an increased likelihood to engage in maladaptive social behaviour (Nesdale & Lambert, 2008). It makes sense that children who were rejected by their peers are more likely to experience negative outcomes. However, even children who were not actually rejected, but anticipate rejection (i.e., children high on rejection sensitivity; Park 2007), were more likely to experience negative outcomes. Downey, Lebolt, Rincón, and Freitas (1998) found that children (in Grades 5 to 7) who angrily expected rejection became more distressed compared to children who were less afraid of being rejected. Downey et al. also found that children who were high on rejection sensitivity had more social conflicts (with peers and teachers), were more disruptive and oppositional, and were less engaged in school. Being sensitive to rejection appears to be related to a variety of negative outcomes. It is possible that those who are most afraid of being rejected are more likely to experience social anxiety given that social anxiety involves being fearful of being rejected by others. In the present study, I examined the relation between body image dissatisfaction, social anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation. I investigated whether fear of being negatively evaluated influenced the relation between body image dissatisfaction and social anxiety in adolescents, with the aim of informing current body image intervention strategies. In the literature review, an overview of the literature on the variables being studied is discussed which includes the impact and prevalence of body image dissatisfaction and social anxiety, as well as the relation between these two variables. Fear of negative evaluation is explained and considered in relation to body image dissatisfaction and social anxiety. Further, any longitudinal studies involving these variables are discussed. A detailed description of the study’s objectives and methodology follows. The results are then presented and discussed as well as the future implications and the contribution of my research.

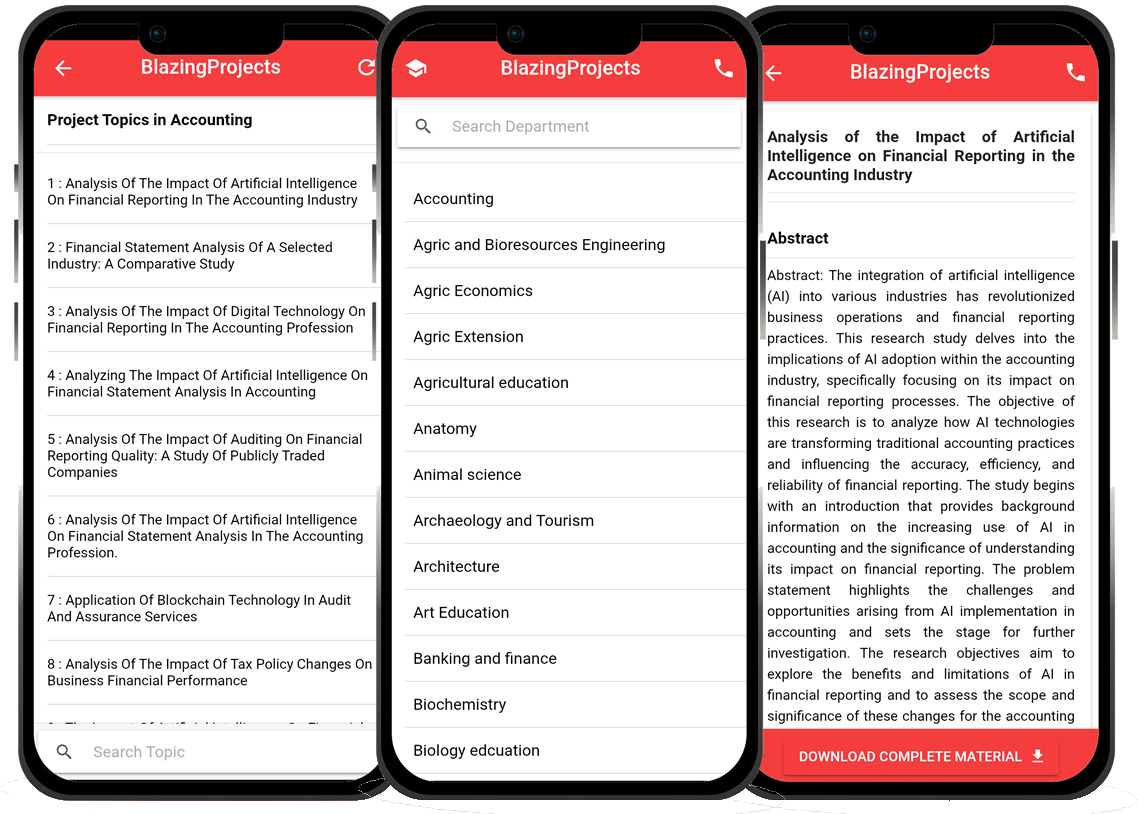

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Analysis of the effects of climate change on plant species distribution and diversit...

The project focuses on investigating the impact of climate change on the distribution and diversity of plant species within a specified region. Climate change i...

Exploring the Effects of Climate Change on Plant Diversity in a Tropical Rainforest ...

The research project titled "Exploring the Effects of Climate Change on Plant Diversity in a Tropical Rainforest Ecosystem" aims to investigate the im...

Investigating the Effects of Climate Change on Plant Phenology and Productivity....

In this research study, the focus is on investigating the impacts of climate change on plant phenology and productivity. Climate change, characterized by shifts...

Effects of Climate Change on Plant Species Distribution and Diversity...

The project topic "Effects of Climate Change on Plant Species Distribution and Diversity" focuses on investigating the impact of climate change on the...

Exploring the effects of climate change on plant biodiversity in a local ecosystem...

The project topic, "Exploring the effects of climate change on plant biodiversity in a local ecosystem," delves into the crucial relationship between ...

Exploring the Effects of Climate Change on Plant Species Distribution and Biodiversi...

The project topic "Exploring the Effects of Climate Change on Plant Species Distribution and Biodiversity" delves into the significant impact that cli...

Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Plant Species Diversity in a Tropical Ra...

The project titled "Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Plant Species Diversity in a Tropical Rainforest Ecosystem" aims to investigate the ef...

Effects of Climate Change on Plant Growth and Physiology: A Case Study in a Local Ec...

The research project titled "Effects of Climate Change on Plant Growth and Physiology: A Case Study in a Local Ecosystem" aims to investigate the impa...

Effects of Climate Change on Plant Physiology and Adaptation Strategies...

The research project titled "Effects of Climate Change on Plant Physiology and Adaptation Strategies" aims to investigate the impact of climate change...