SICKLE CELL DISEASE AWARENESS AMONGST COLLEGE STUDENTS

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objectives of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Sickle Cell Disease2.2 Historical Perspective

2.3 Global Prevalence of Sickle Cell Disease

2.4 Genetic Basis of Sickle Cell Disease

2.5 Clinical Manifestations

2.6 Diagnosis and Screening

2.7 Management and Treatment

2.8 Challenges in Sickle Cell Disease Awareness

2.9 Importance of Education and Awareness

2.10 Initiatives for Sickle Cell Disease Awareness

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Design3.2 Sampling Methods

3.3 Data Collection Techniques

3.4 Data Analysis Procedures

3.5 Ethical Considerations

3.6 Research Validity and Reliability

3.7 Limitations of the Research Methodology

3.8 Research Assumptions

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Overview of Research Findings4.2 Demographic Analysis of Participants

4.3 Awareness Levels of Sickle Cell Disease

4.4 Factors Influencing Awareness

4.5 Effectiveness of Awareness Campaigns

4.6 Comparison with Previous Studies

4.7 Recommendations for Improvement

4.8 Implications for Future Research

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Findings5.2 Conclusion

5.3 Contributions to Knowledge

5.4 Implications for Practice

5.5 Recommendations for Action

5.6 Areas for Future Research

Project Abstract

ABSTRACT

This descriptive study was designed to investigate if college students attending a midwestern university are aware of the clinical manifestations, treatments, and genetic counseling methods for sickle cell disease. This study was also devised to determine whether or not students, who are more likely to be genetically affected by sickle cell disease, are more or less aware of their sickle cell disease status. Two hundred and fiftynine (259) University of Illinois Urbana- Champaign (UIUC) students, 18 years and older, enrolled in one of the three following Community Health courses Community Health Organizations (CHLH 210), Health Care Systems (CHLH 250), and Introduction to Medical Ethics (CHLH 260) were used as study participants. These 259 participants were assessed on their general knowledge of sickle cell disease (SCD). Participants in this study were given a sickle cell disease questionnaire that consisted of 11 questions on sickle cell incidence, prevalence, origin, counseling methods, and knowledge of trait status. Frequency tables, cross-tabulations, and chi-square tests were used to evaluate the variations of existing SCD knowledge among students. Results illustrated that participants did have some general knowledge of sickle cell disease. Study results showed a statistical difference in the response rates for males and females when surveyed on the life expectancy of sickle cell disease (p = .047). Other results showed no statistical differences in response rates between ethnicities group and age.

Project Overview

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND OF STUDY

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited blood disorder caused by abnormal hemoglobin (Creary, Williamson, & Kulkarni, 2007). Sickle cell disease limits the oxygenating role of hemoglobin, resulting in the damaging or the “sickling” of the red blood cells (Barakat, Schwartz, Simon, & Radcliffe, 2008). This disorder affects all parts of the human body and differs widely among individuals (Bloom, 1995). In 1910, Dr. James Herrick, a Chicago physician, was the first American to formally report and identify elongated, sickle-shaped hemoglobin in an anemic Grenadian student’s blood smear. Herrick coined the now familiar term “sickle cell” (Ogamdi, 1994). The sickleshaped red blood cells described by Herrick caused several complications, including chronic anemia, vaso-occlusive pain episodes, ischemic organ damage, infections, small stature, and delayed puberty (Barakat et al., 2008). For many generations sickle cell disease has been a prevalent disorder in Africa. Reports show that sickle cell disease was a well-known disorder in West Africa and that the West African natives had several local names for this disease before it was discovered in America (Reid & Rodgers, 2007). Sickle cell disease affects millions of people throughout the world, and it is found to be the most common blood disorder among families whose ancestors came from SubSaharan Africa, South America, Cuba, Central America, Saudi Arabia, India, and the Mediterranean regions (Creary et al., 2007). Studies indicate that approximately 1 in 12 African-Americans are heterozygous for the disorder, and approximately 1 in 500 African-American newborns are diagnosed annually with SCD (Boyd, Watkins, Price, Fleming, & DeBaun, 2005). Also, the life expectancy for SCD has doubled since the 1960s. Before that time, few patients lived to reach adulthood (Platt, Brambilla, Rosse, Milner, Castro, Steinberg, & Klug, 1994).

It was not until the 1970s that this blood disorder began to capture public attention in the United States. Prior to that time, many researchers held numerous misconceptions about the nature and course of the disease. Richard Nixon was the first president to make sickle cell disease a matter of national concern by signing the Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act of 1972 (Cerami, 1974). In 1971, President Nixon focused his health message to Congress on sickle cell disease, which at that time was a virtually unknown inherited blood disorder in the African-American community (Reid & Rodgers, 2007). The 1972 act set the foundation for funding toward sickle cell screenings, counseling programs, and the development and distribution of sickle cell anemia educational materials to the general public (Woolley & Gerhard, 1999). With the help of President Nixon, several sickle cell disease research organizations were created, such as the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America (SCDAA), which was established by Charles Whitten in 1972. The SCDAA was designed to improve the quality of life for patients and families with sickle cell disease (Reid & Rodgers, 2007).

After the 1970s, the public’s focus unfortunately shifted once again. The new law, which first established sickle cell education, genetic screenings, and counseling, was stated to be “fraught with controversy” (Treadwell, McClough, & Vichinsky, 2006). Even the African-American community, which has a higher probability of inheriting SCD, began to regard informed reproductive decision methods, such as screening and counseling, with trepidation and distrust (Treadwell et al., 2006). After President Nixon turned sickle cell disease into a national priority, legislators quickly began to pass laws that mandated premarital and pre-school screenings for sickle cell disease. The U.S Air Force began to deny airmen, who were diagnosed as carrying the sickle cell trait, occupational opportunities if they were applying to be pilots or co-pilots, and insurance companies even increased premiums for individuals with the trait (Reid & Rodgers, 2007). The American people began to view these new legislative policies as genocidal, and these policies were eventually overturned (Reid & Rodgers, 2007).

The lack of national concern for SCD created a barrier in health care. Complications due to the sickling of the red blood cells therefore continue to be a significant issue to patients and physicians in today’s medical world. Physicians remain puzzled by the biological and clinical intricacies of SCD, and SCD researchers are trying to find a cure to reverse the “sickling effect” in the human body.

1.2 PURPOSE OF STUDY

Sickle cell disease continues to be a global health problem that presents major challenges to our health care systems. The reviewed SCD literature expresses a dire need for more public education and awareness on SCD in the United States. In comparison with other chronic diseases and blood disorders, sickle cell disease remains one of the least understood and puzzling medical conditions by health care workers and the general public, as well as the least funded blood disorder (Clarke & Clare, 1981). Misleading descriptions of sickle cell disease, as a race-related disease during the past few decades, have significantly contributed to the rise in the public’s misunderstanding of sickle cell disease (Clarke & Clare, 1981).

In addition, existing research on SCD focuses on the awareness of the disease among college students attending Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) where the majority of participants are of African-American descent. Therefore, a paucity of information exists regarding the awareness among college students attending midwestern universities. This study therefore attempts to determine if college students attending a midwestern university are aware of the clinical manifestations, treatments, and genetic counseling methods for sickle cell disease. This study hopes to determine whether or not students, who are more likely to be genetically affected by this disease, are more or less aware of their SCD status.

1.3 RESEARCH QUESTION

This research study attempts to answer the following three questions by using a sickle cell disease questionnaire to survey college students on their existing knowledge of sickle cell disease.

Research Question 1

How knowledgeable are midwestern college students on background information regarding sickle cell disease?

Research Question 2

Do any significant differences exist in awareness between ethnic groups or groups of students who have a higher probability of inheriting sickle cell disease traits?

Research Question 3

Do any significant differences exist in awareness between gender groups?

1.4 DEFINITIONS

For the purpose of this literature review, these phrases, frequently referenced throughout the text, are defined as follows:

ï‚· Genetic counseling: Communication process between health care provider and client that emphasizes and provides accurate and up-to-date information about a genetic disorder in a sensitive and supportive, non-directive manner (SCDAA, 2005).

ï‚· Hemoglobin: Chemical substance (an iron containing protein) of the red blood cell, which carries oxygen to the tissues, and gives the cell its red color (SCDAA, 2005).

ï‚· Hemoglobin A (HbA): Hemoglobin is composed of two alpha globins and two beta globins, normally produced by children and adults (Jones, 2008, p. 119).

ï‚· Hemoglobin C trait (AC): Inheritance of one gene for the usual hemoglobin (A) and one gene for hemoglobin (C). A person who has the hemoglobin C Trait (AC) 6 is a carrier of the hemoglobin C gene, and is not affected by the gene (SCDAA, 2005).

ï‚· Hemoglobin C disease: A person has both HbS and HbC and is often referred to as “HbSC.” Hemoglobin C causes red blood cells to develop. Having just some hemoglobin C and normal hemoglobin, a person will not have any symptoms of anemia. However, if the sickle hemoglobin S is combined with the target cell, some mild to moderate anemia may occur (UMMC, 2010).

ï‚· Hemoglobin E disease: Similar to sickle cell-C disease except that an element has been replaced in the hemoglobin molecule under certain conditions, such as exhaustion, hypoxia, severe infection, and/or iron deficiency (UMMC, 2010).

ï‚· Hemoglobin S-beta-thalassemia: An inheritance of both the thalassemia and sickle cell genes. The disorder produces symptoms of moderate anemia and many of the same conditions associated with sickle cell disease, but to a milder degree (UMMC, 2010).

ï‚· Sickle cell anemia (SS): An inherited disorder of the red blood cells in which the hemoglobin is different from the normal hemoglobin. This unusual hemoglobin results in the production of unusually shaped cells and is referred to as “HbSS.” It is the most common and severe form of the sickle cell variations (SCDAA, 2005).

ï‚· Sickle cell disease (SCD): An inherited disorder of the red blood cells in which one gene is for sickle hemoglobin (S) and the other gene is for unusual hemoglobin such as S, C, Thal (SCDAA, 2005; UMMC, 2010). 7

ï‚· Sickle cell trait: A person carrying the defective gene, HbS, but also has some normal hemoglobin HbA. Persons with the sickle cell trait are usually without symptoms of the disease, but mild anemia may occur under intense, stressful conditions, exhaustion, hypoxia (low oxygen), and/or severe infection. The sickling of the defective hemoglobin may occur and result in some complications associated with sickle cell disease (UMMC, 2010).

1.5 ASSUMPTIONS

The following two assumptions have been made:

1) The data are reliable and accurate measurements of a student’s awareness, and

2) each participant answered the questionnaire without coercion.

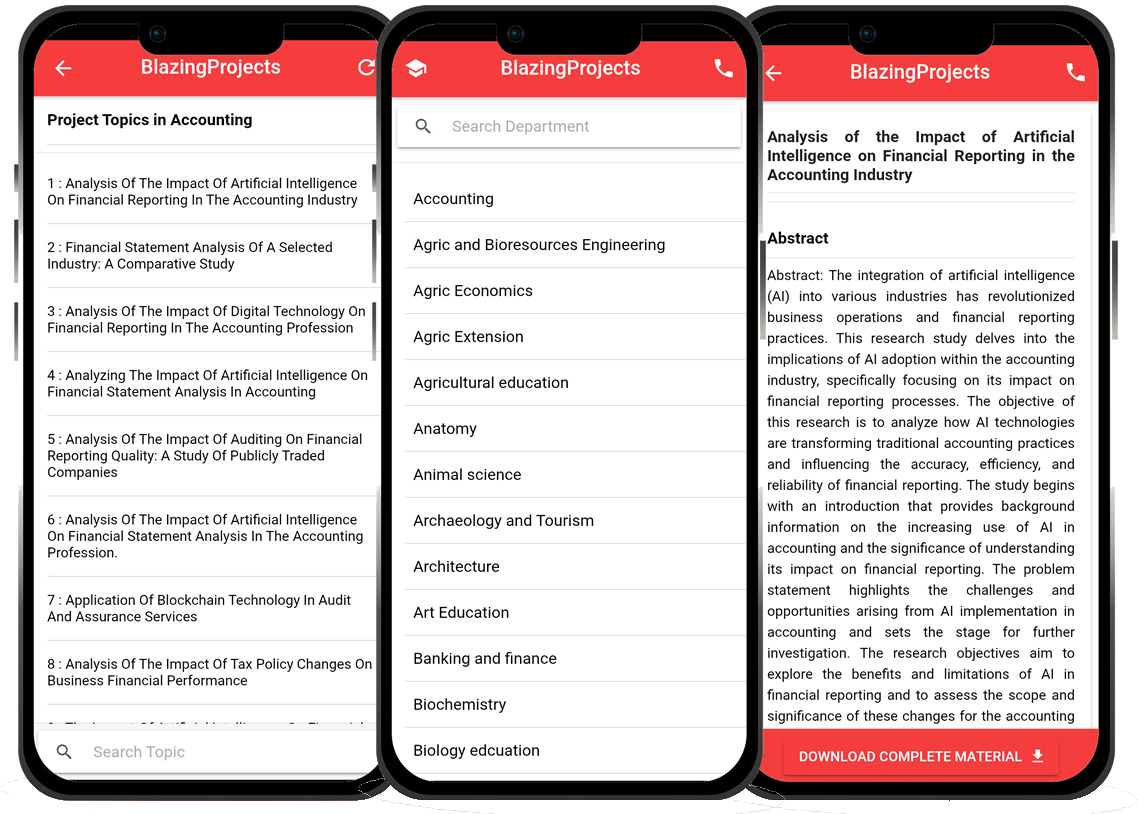

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Assessing the effectiveness of multimedia simulations in teaching cellular respirat...

...

Exploring the impact of outdoor fieldwork on student attitudes towards biology....

...

Investigating the use of concept mapping in teaching biological classification....

...

Analyzing the influence of cultural diversity on biology education....

...

Assessing the impact of cooperative learning on student understanding of genetics....

...

Investigating the effectiveness of online quizzes in promoting biology knowledge re...

...

Exploring the use of storytelling in teaching ecological concepts....

...

Analyzing the impact of teacher-student relationships on student achievement in biol...

...

Investigating the role of metacognitive strategies in biology learning....

...