THE PHENOMENON OF BUILDING MAINTENANCE CULTURE, NEED FOR ENABLING SYSTEMS

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Building Maintenance2.2 Historical Perspectives

2.3 Importance of Building Maintenance

2.4 Types of Building Maintenance

2.5 Factors Influencing Building Maintenance

2.6 Building Maintenance Technologies

2.7 Building Maintenance Best Practices

2.8 Economic Implications of Building Maintenance

2.9 Sustainable Building Maintenance Practices

2.10 Future Trends in Building Maintenance

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Methodology Overview3.2 Research Design

3.3 Data Collection Methods

3.4 Sampling Techniques

3.5 Data Analysis Procedures

3.6 Ethical Considerations

3.7 Research Limitations

3.8 Research Validity and Reliability

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Overview of Research Findings4.2 Statistical Analysis of Data

4.3 Interpretation of Results

4.4 Comparison with Existing Literature

4.5 Discussion of Key Findings

4.6 Implications of Findings

4.7 Recommendations for Practice

4.8 Areas for Future Research

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Findings5.2 Conclusion

5.3 Contributions to Knowledge

5.4 Practical Implications

5.5 Recommendations for Further Action

Project Abstract

ABSTRACT

This article is based on experience through practice and training, augmented by a literature review on the phenomenon of building maintenance generally, and with reference to the Nigeria case where maintenance of buildings especially in the public sector has attained a crisis. The overarching objective is to delve into the nature of the maintenance problem, issues entailed and how they can be tackled in a structured system so as to somewhat resolve the crisis of poor, or lack of, maintenance which renders building unsightly and unattractive.

Keywords Building maintenance, Legislation for maintenance, Professional practice, Business community, Training institutions, public media.

Project Overview

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Building stock is part of a nation’s wealth, and its quality and condition reflects not only on the prosperity of the nation but also the social values attached to it. As the building stock ages, it is pertinent that an adequate level of maintenance be sustained to ensure the economic value of the buildings. The proper maintenance of buildings is an important program for sustainable development, and plays a major role towards national prosperity and a healthy environment (Zulkarnain et al,: 2011). This is, in addition to the production of new buildings, a key role for the building industry.

The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) in the report ‘Our Common Future’ (WCED: 1987) defines ‘sustainable development as follows: Sustainable Development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Maintenance forms a critical part in the involvement of the building industry in creating a sustainable environment. This issue is now widely recognized as demonstrated from the conclusions and recommendations of the UNIDO organized “First Consultation on the Construction Industry” held in Tunisia in May 1993. In a key part of the conclusions, the gathering observed that: “Generally, maintenance and rehabilitation of buildings and infrastructures are neglected aspects of construction activities in developing countries.

Governments should set up policy guidelines for integration maintenance and rehabilitation in cost analysis, estimating and contracting for new works. Steps should also be taken for adequate maintenance of existing housing stocks, service networks and other infrastructures.” Thus the maintenance of building and infrastructure is seen as a matter requiring the attention of not just the industry but policy makers at high government levels. The connection of a healthy living environment with proper social values has been made by several scholars and underlines the importance of maintaining a sustaining culture that continuously awakens society to the need for attention in keeping the resources represented by building. It is therefore clear that the maintenance of buildings ought to be a vigorous exercise within the industry and society in general. The objective goals can be spelt out as follows, to:

ï‚· reduce the total cost of building operation

ï‚· preserve invested value during the expected lifetime

ï‚· maintain the useful qualities of the building at a level chosen beforehand

ï‚· preserve the aesthetic qualities of the building at a level chosen before

ï‚· maintain the necessary safety and sanitary level

ï‚· ensure continued adherence to the building regulations

We can from here move on to the observation that buildings will always need to be maintained. As soon as a facility is built, it begins to decay. This downward curve is a natural trend that can only be reversed by human intervention-which may range from the minor and continuous process of maintenance to major rehabilitation and renovation (Lozano: 1990). This is because despite the evidence of Egypt and ancient Greece, buildings do wear and tear. Materials deteriorate with time and a need arises to recoup the fading glory. The perception by the community of the place of maintenance is related to several other factors. In modern city living, this matter cannot be divorced from the alienation from nature that tends to be a natural consequence. Open space which constitute a good portion of the public domain, and which underlines the urban fabric as a shared habitat, may be seen as no more than wasted opportunity to develop and make money.

Poor maintenance in the urban context may be related to the weak sense of community and therefore weak commitment t the quality of the shared living environment. Moreover in our environment exposure to dust, rain and other elements of the weather have proved to be complicating factors in the well-being of buildings. Architecture contributes to the physical environment primarily through its aesthetical quality and it is from here that the first signals of a crisis usually emanate.

1.2 THE CRISIS OF BUILDING MAINTENANCE IN NIGERIA

Building maintenance in Nigeria has not received much attention in the past as the emphasis is on the development of new buildings (Coetzee: 1999). This is also echoed by other researchers, (see Yiu:2008; Lateef:2008 and Wood:2003) who observe that there is apparent lack of maintenance culture, and that focus has solely been on the construction of new buildings and pretty much total neglect of maintenance which commences immediately the builder leaves site. This practice therefore, makes a compelling case for studying the various factors affecting building maintenance with a view to recommending enabling systems as a solution to the identified problem. Just like it has been observed by other researchers on the phenomenon of building maintenance (Waziri, et al;: 2013), a crisis looms in Nigeria due to non-maintenance of building stocks. Built forms consisted of buildings and other infrastructural development are running down and losing their utility value due to lack of maintenance. This matter, though incessantly highlighted especially by the press dailies, does not seem to have captured the attention of policy makers and others relevant parties entrusted with the custody and use of the existing building stock. Numerous factors affecting building maintenance have been revealed by an avalanche of studies. Assaf, for instance (Assaf: 1996), posits the argument that design and construction faults that affect maintenance of buildings are defects in both civil and architectural design, workmanship, materials, finishes and lack of a maintenance regime. Whatever factors that may be identified as a factor affecting building maintenance, the overarching single-most problem is the lack of a maintenance culture, as evidenced by lack of upkeep and repair.

Granted, our responses in design have been influenced heavily by borrowing blindly, without any guiding standards with regard to specifications of materials and finishes, from other so-called ‘developed cultures’. This importation of solutions wholesale from other lands that have different climatic conditions will always prove inadequate despite what the facades may show. Besides, the cultures we are borrowing from may have a strongly grounded maintenance culture which we do not have. Many of our design solutions have been accepted in this environment uncritically and have over time been proven to be environmentally unfit. Many examples abound on the design borrowings. Firstly is the case of flat roofs that were in vogue during the decades of seventies and eighties, which have posed major flaws due to cracks and leakages. Secondly, conflicts relating to the differences in our climate and rainfall patterns require that our design elements often look at things from first principles rather than adopting other people’s solutions. The pull towards aesthetic glamour can and does have its pitfalls. The practicalities of building must always seek to put the shelter aspect first, shelter from rain, from cold and other vagaries of the weather. It is when that fundamental goal of architecture is sacrificed for secondary issues that the sustainability of the work comes into question.

Architecture that even briefly abrogates the essential aim of providing shelter will find itself unable to last for long. Today, fashion seems to have led us toward the glass tower as an acceptable, indeed desirable, city form. The shortcomings of this new architecture can be felt by all who work in these new buildings and also by those who will be exposed to the glare and reflections that emanate from them. It is an architecture that runs counter to common sense and which in time shall be rendered and declared obsolete. To try and sustain comfortable working environments in these buildings will take more money than is affordable and without absorbing the body of the resultant strain. A third reason therefore is indicated by the lack of rigorous examination of our environment as a prelude to the formulation of design response in our buildings. There is no momentum in the creation of responses in choice of materials, design of the building fabric, clarification of aesthetic appropriateness that recognizes the differences in our environment. This observation must be underlined by the further observation that building stock cannot be expected to deliver if in the first place it was inappropriate for the context it was placed in. Coupled with this is the allocation of resources that would go toward rectifying the situation. Budgetary allocations for maintenance have been easy casualties in an era of austerity measures. It has to be expected that sooner or later a buildings will require major maintenance and that all the time the building fabric and services are in use, continuous maintenance attention is required and therefore expenditure. It is necessary that owners and managers begin to recognize the proper place of maintenance in their resource allocation and to respond positively. It does not look like a commonly held realisation that buildings will occasionally demand a coat of paint. Underlying all this is the dearth of acceptance of the need to maintain.

The information base that needs to be available and fully disseminated does not exist. The common building owner does not always appreciate the fickle nature of the material we use. There is almost an expectation that once a building is put up it can and should serve forever. It seems that only people with the technical training will fully appreciate and thereby anticipate the necessary commitment to material after a lapse of time. Public education on this matter is lacking and with it the chance to build an attitude to the well being of the building stock without which we cannot expect to get over the crisis. We need to develop a maintenance ethic, a culture that recognizes the inherent need to maintain buildings. This maintenance ethic is lacking in Nigeria, and this can be demonstrated by the attitude taken by institutions in the political, economic and educational sectors where maintenance is at best a peripheral concern. In the event, facilities are deteriorating at an alarming rate with the attendant consequences in the decline in value, decline in performance standards an when looked at from a broad sociological dimension, they become contributors to the decline of social mores. The state of affairs that prevails in the condition of facilities in the nation cannot fail to have an effect on the well being of the people. This view is supported by the various post-mortem studies on the so called ‘Modern Movement’ in architecture, which has been in vogue in pretty much all countries of the world for most of this century.

Building stock in a state of perpetual decline means that resources have to be devoted to reconstruction and that the prosperity represented in those investments declines. The effect of poor, or non-existent, maintenance is mainly felt in the urban areas. One reason is the prevailing densities in urban areas which lead to intense usage of buildings and facilities, but also due to the structural and financial weakness that have hampered greatly the local authorities. To address broadly the issue of a sustainable living environment, it may require thorough reforms in the administration of local areas. It is an issue, however, that cannot be ignored in the rural areas where meager resources are committed to the provisions of shelter. Several forums have addressed the crisis of maintenance of especially public buildings in Kenya, and an emergent observation is that need for creation of a tradition for maintaining our building facilities does exist and is real. The realization envisages a situation where a reliable system of organization ought to be in place so as to address the issue when the need arises and, to continuously monitor the state of our building stock. To do this, it is necessary to institute measures at an institutional level from where a culture may permeate down to the general populace. It is necessary that prominent examples of a new attitude be set. Some of the areas where these can be instituted are outlined below but a high degree of commitment needs to be exercised if any of it is going to be useful.

1.3 LEGISLATION FOR MAINTENANCE

The law, as regards maintenance, is at the moment highly deficient and is hardly able to address the issue. The one glaring area of deficiency is in the setting of standards that have to be maintained. It must be appreciated though that the formulation of standards is itself and involving task and can only be accomplished by a wide spectrum of professionals. The lack of maintenance standards calls for action form professional and the building industry. Areas that require to be addressed include the process of maintenance which in itself must include a framework for monitoring. It needs to be stated clearly who will do the monitoring. It is necessary to state unambiguously what kind of standards we intend to keep as a nation in our building stock. We should be able to formulate some kind of guidance on what our buildings ought to look like and at what point the value of the stock ought to be rehabilitated. By so doing we shall be asserting the national interest in the value of our building stock, but more important we shall be creating a gauge upon which we may see when action requires to be taken and what action that may be. The creation of new assets is part of the economic activity.

The decimation of what exists however may, in many situations be regarded as counter to that. It is necessary to examine the possibilities of preserving what exists through renovation or rehabilitation before the option of demolition is considered. At the moment this country lacks guidelines in this aspect and formulation of such may be a priority. Laws do exist that allow historically important buildings to be preserved, it may be about time to exercise vigilance in a broader way to oversee buildings that may have economic importance and which currently may be going to waste through the euphoria of redevelopment.

1.4 PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE

Professionals in the design team have a big role to play in ensuring a tradition recognizing the centrality of maintenance. In current practice the normal professional service has been narrowed as to preclude certain services that they may be useful in prolonging the life of buildings. One such area is the study of feasibility. It is necessary that before commitment is made in investment, certain fundamentals be established regarding the demand for the facility and ‘life cycle’ costing. In the book of Laws of Nigeria which regulates the practice of Architects and Quantity Surveyors describes feasibility study as a special service not expected in the normal services offered by the Architect. In a normal engagement therefore, an Architect is not required to get into a feasibility study unless the client expressly asks for it, for which there will be an extra charge. In recognition of the role of a feasibility study in the management of building stock, it may not be far-fetched to make it a mandatory requirement for buildings that are especially of appreciable sizes. Secondly, it should be required that the designer give some guidance as to maintenance needs. In much the same manner as when one purchases an electronic device, the developer of a building facility ought to get a manual of maintenance indication what and when elements will need attention. It is not always appreciated that all elements in a building deteriorate over time, some faster than others. The various categories of maintenance need to be spelt out in the frequency required of them. In the current setup, contract documents allow for a defects liability period of only six months within which defects in a new building can be made good. No provision is made, however, for longer periods of assessment and this may be contributing to the state of negligence that one perceives in the buildings in Kenya. The professional community should now look toward the creation of frameworks that ensure continued assessment o buildings to preserve their worth for longer periods. To do this, it is necessary that information about products be made available both to the designers who specify them and to the builders who implement the designs. Whereas it is possible to make visual judgment on certain elements, other parts of a building will be hidden and hence require more complex analysis that only expert knowledge will allow for accurate prediction as far as longevity is concerned.

Thus without a reliable system to predict longevity, any system of maintenance will find itself breaking down. Maintenance involves expenditure and this translates to forward planning and budgetary control. In this kind of situation good management will require to have a forewarning as to what areas may require allocations and to what magnitude. It is in this light that information about the performance of building elements would become useful in building the culture of maintenance. Such information should be provided by manufacturers of building materials and finishes that then should be confirmed by statutory bodies. One could site as a matter of illustration the usage of building material. The durability of materials in varied circumstances of application is central to the subject of sustainable building. The study of this should be an ongoing concern and sufficiently important to justify a fully fledged research institute on the lines of similar centre in agriculture and medicine.

The recent creation within the University of Nairobi of a Housing and Building Research Institute is a step in the right direction and all those involved in the building industry must support and help to develop this institute. Among their major concerns must be an attempt to fill the gap on information regarding materials both in the popular use and in high technology. The generation of information regarding the durability of materials and building elements is a key factor in the strategies that will keep buildings longer on the market. This information is however not always forthcoming and in the cases where a manufacturer provides it, the marketing slant sometimes gets the better of them. It is necessary to verify this through an independent body which of course is not available in Nigeria today. Beyond that Research into longevity should be given the seriousness befitting the critical wealth of the nation that buildings are. The practice of maintenance of building brings to focus the critical position of the contractor. In maintenance the contractor tends to deal more directly with the client, and the contractor’s advice is sought and taken seriously. But the place of the contractor during the design stage has never been recognized as anything more than a functionally who takes and implements decisions may be others. And yet, this is a key player in the creation of architecture and through his involvement amasses considerable experience which can be drawn upon to influence better design.

The contractor as a full member of the design team is probably an overdue arrangement. Granted that it would involve major changes in current arrangements, it is an occasion that would contribute toward higher standards of building and thus longer life in them.

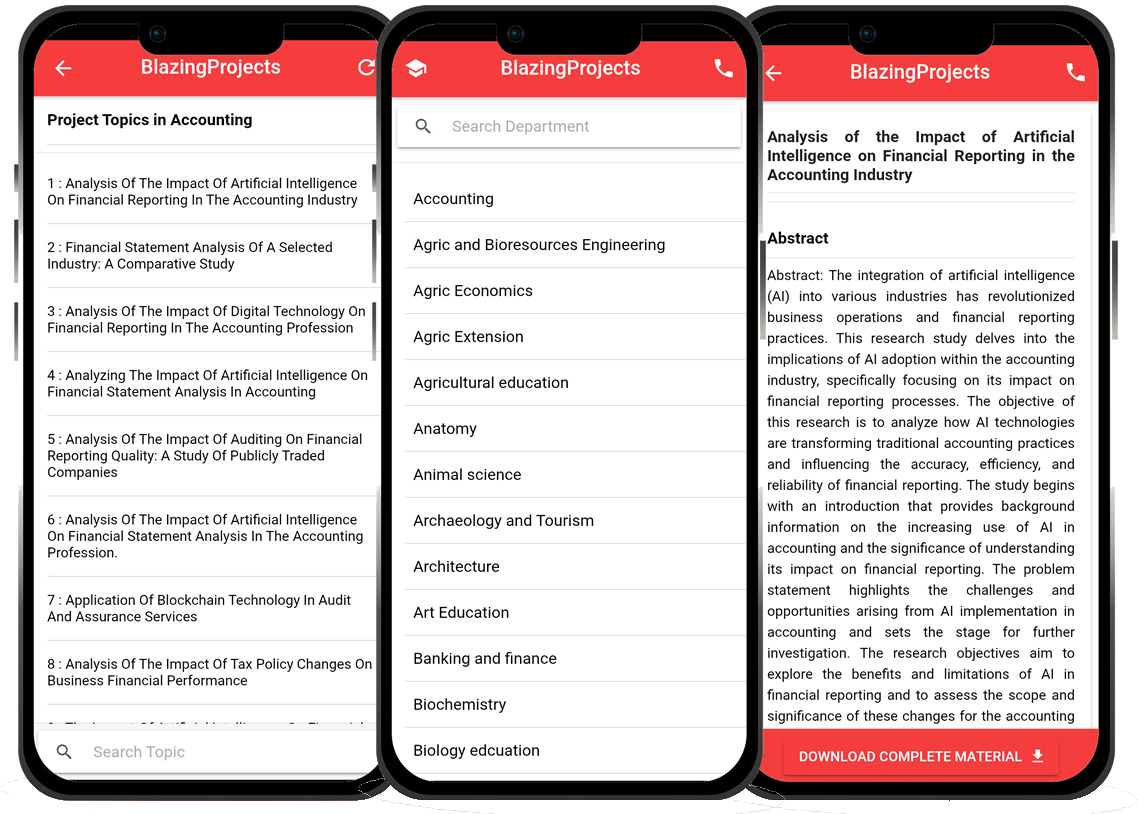

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Exploring the Integration of Green Technology in Urban Architecture Design...

The project topic of "Exploring the Integration of Green Technology in Urban Architecture Design" aims to investigate the incorporation of sustainable...

Exploring Sustainable Design Solutions for Urban Housing Developments...

The project on "Exploring Sustainable Design Solutions for Urban Housing Developments" aims to address the pressing need for sustainable and environme...

Utilizing Sustainable Materials and Design Techniques for Affordable Housing in Urba...

The project topic "Utilizing Sustainable Materials and Design Techniques for Affordable Housing in Urban Areas" addresses the critical issue of housin...

Design and Analysis of Sustainable Housing Solutions for Urban Slums...

The project on "Design and Analysis of Sustainable Housing Solutions for Urban Slums" aims to address the pressing issue of inadequate housing in urba...

Designing Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Community Centers for Urban Spaces...

The project "Designing Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Community Centers for Urban Spaces" aims to address the growing need for environmentally conscious...

Designing Sustainable Urban Spaces: Integrating Green Infrastructure in High-Density...

The project topic "Designing Sustainable Urban Spaces: Integrating Green Infrastructure in High-Density Cities" focuses on addressing the pressing nee...

Adaptive Reuse of Abandoned Industrial Buildings: A Sustainable Approach in Urban De...

The project topic "Adaptive Reuse of Abandoned Industrial Buildings: A Sustainable Approach in Urban Development" focuses on the transformation of aba...

Exploring Sustainable Design Strategies for Urban High-rise Buildings...

The project topic "Exploring Sustainable Design Strategies for Urban High-rise Buildings" delves into the critical realm of sustainable architecture w...

Designing Sustainable Housing Solutions for Urban Slums...

The project topic, "Designing Sustainable Housing Solutions for Urban Slums," seeks to address the critical issue of inadequate and substandard housin...