AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF UBASAA IRON WORKING SITE, CHIKUN LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF KADUNA STATE, NIGERIA

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Historical Background of Iron Working Sites2.2 Evolution of Iron Working Techniques

2.3 Importance of Iron Working Sites in Archaeology

2.4 Previous Studies on Iron Working Sites

2.5 Cultural Significance of Iron Working Sites

2.6 Tools and Artifacts Found at Iron Working Sites

2.7 Economic Impact of Iron Working Sites

2.8 Social Organization around Iron Working Sites

2.9 Technological Advancements in Iron Working

2.10 Conservation Efforts for Iron Working Sites

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Design3.2 Data Collection Methods

3.3 Sampling Techniques

3.4 Data Analysis Procedures

3.5 Ethical Considerations

3.6 Research Limitations

3.7 Timeframe for the Study

3.8 Budget and Resource Allocation

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Overview of Findings4.2 Analysis of Excavated Artifacts

4.3 Interpretation of Site Layout

4.4 Comparison with Other Iron Working Sites

4.5 Cultural Implications of Findings

4.6 Socio-Economic Impact of Discoveries

4.7 Technological Insights from Artifacts

4.8 Implications for Future Research

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Conclusion5.2 Summary of Research Findings

5.3 Contributions to Archaeological Knowledge

5.4 Recommendations for Future Studies

5.5 Implications for Conservation Efforts

Project Abstract

ABSTRACT

This research work focuses on the study of iron working site at Ubassa in Chikun Local Government Area of Kaduna State. The work concentrates on the documentation of the evidence of iron working in the area and how this industry affected the environment and human development in the area and its surroundings in general. The research has been conducted using traditions, archaeological survey, and classification and analyses of materials. The oral traditions collected focused on the history of the people who worked iron in the area including the history of iron working and its impact on the different aspects of human life. An archaeological survey of the site involved mapping of the site by determining the size of the site and the distribution of cultural materials on the site. Classification and analysis of artifacts and features was carried out using attributes observable through the naked eyes. Findings from this research work has been able to reveal that, the workers of iron in this area had a good understanding of their natural environment. The role the environment played in the choice of iron smelting sites has been demonstrated in this work as well. On the whole, the research although in its preliminary stage has illuminated aspects of the history of iron working at Ubassa site in Kaduna State.

Project Overview

INTRODUCTION

This research is concerned with Ubasaa abandoned industrial site in Buruku District, Chikun Local Government Area of Kaduna State, Nigeria. (figure 1) The people who occupy parts of the research area today belong to the Gbagyi ethnic group The site has good evidence of past human activities in form of grinding stone, furnaces, tuyeres and iron slag. Few archaeological works have been carried out in the Buruku area (Abdulkadir, 2008; Marcus, 2008; Bello, 2009) and all of these did not involve survey and mapping for proper documentation of the archaeological materials. These sites are all found in locations where they are prone to both human and natural destruction. This current research is focused on the Ubasaa iron working site and it is justified by the fact that, the site is rich in cultural materials which have been preserved in relatively good state. This site according to oral informants is said to have been a big industrial site but parts of it have been destroyed by the Kaduna Ministryof Environment in their attempt to create a forest reserve (forest plantation). The site was discovered through the help of some forest guards (Mr. Sylvester Boyi, Solomon Boyi,, Monday Thomas, Dan Kaduna Dandadu, and Joshua Ali 2013) under the Kaduna State Ministry of Environment. Two localities of cultural materials were identified on the site and for the purpose of clarity, have been designated as localities A and B and they are about two kilometers apart.

1.2 Statement of Research Problem

There has been no archaeological research conducted on Ubasaa site despite its huge archaeological potentials. This site with its extensive size and enormous evidence which point to a big iron working industry can only be compared with the Tsauni iron working industry in the Zaria area. Considering the impact of iron working technology on the environment and human life in general, it becomes pertinent to investigate this industry to find out whether it had some links with the Tsauni industry which is not too far away from it, and how it impacted the immediate environment and human life in that part of the present Kaduna state. The findings from this study are potentially useful for addressing current technological and ecological needs. Apart from this, the site is under serious threat by agents of destruction like human activities such as farming, forestry plantation, rearing of cattle as well as natural agents like windstorm and erosion. It is in the light of this that, this current research becomes necessary so as to document the cultural materials that have survived on the site and their history through archaeological and historical methods.

1.3 Aim and Objectives of the Research

The aim of this research is to document evidence of iron working in Ubasaa. Through the following:

• to conduct an archaeological survey and documentation of finds and features on the site

• to collect and document oral tradition on the history of the people of Ubasaa.

• to analyze and interpret data from the site for the purpose of writing aspects of Ubassa history.

1.4 Scope and Limitations of the Research

This research work covers the archaeological survey of Ubasaa site and a comparative study of localities A and B of the site. This research is constrained by the researcher‟s inability to carryout excavation and makes no provision for the dating of samples of the material remains from the site which would limit the researcher‟s explanation and interpretation of the available data.

1.5 Literature Review/ Theoretical Framework

The invention of iron working technology was one of the most important feats in human achievements which had a widespread impact on man‟s life. (Haaland, 1985; Schmidt and Childs, 1985; Odofin, 2010).The study of iron in sub-saharan Africa has been engrossed in arguments and counter arguments. These arguments have given rise to three different schools of thought as regards to the origin of iron working these include; the diffusionist school, the indigenous school and the cautious schools of thought (Okafor, 1995).

Cathage in present- day Tunisia was also said to be one of the donor areas for West African iron technology through the activities of Garamentes which stretches as far as within 200km of Gao in the proximity of river Niger (Andah, 1979; Okafor, 1995). While the debate about the origins was raging, several early dates were accepted for iron working in parts of Africa. For many years dates from Taruga in the Nok culture area have been held as the earliest for iron working in sub-saharan Africa. The date of 500 BC was established for Taruga by (Fagg, 1968; Shaw, 1969; cf. Okafor, 1995). Okafor, (1995) favoured both north and north-east Africa as the source for West African iron technology while some people have associated the beginning and spread of iron working in most parts of Africa with the Bantu and their spread in Africa (Fagan, 1965; Greenberg, 1963; Mason, 1974; Davis, 1966; Posnanky 1968; cf. Okafor, 1995). Goucher, (1990) believed that there was transfer of labour and technology during the era of Atlantic trade (c. 1500-1800) which created an African diaspora.

There are also some scholars that counter the argument against the diffusion, independent invention of iron in West Africa was said to be possible (Kense, 1985; Okafor, 1995) this was as a result of lack of or little archaeological evidence to show that iron technology was in transit from the desert regions from where it is said to have diffused to sub-saharan Africa. Also, lack of similarities in methods (processes and artifacts) of working iron between the donor areas and the recipient regions as expressed by (Andah, 1979; Kense, 1985, and Okafor, 1995) is considered another reason for arguing against the diffusionist model.

The controversy surrounding the origin of iron technology in sub-saharan Africa still remains potent among scholars and focus seems to have shifted from whether the idea of iron metallurgy originated in Africa or not. The technolzogy of iron smelting as it pertains to mode of technological processes of production, types of furnaces as found in different areas and the economic, cultural, social and environmental factors directly or indirectly related to iron working (Andah, 1979; Kense, 1985; Childe, and Schmidt, 1985; Okafor, 1995).

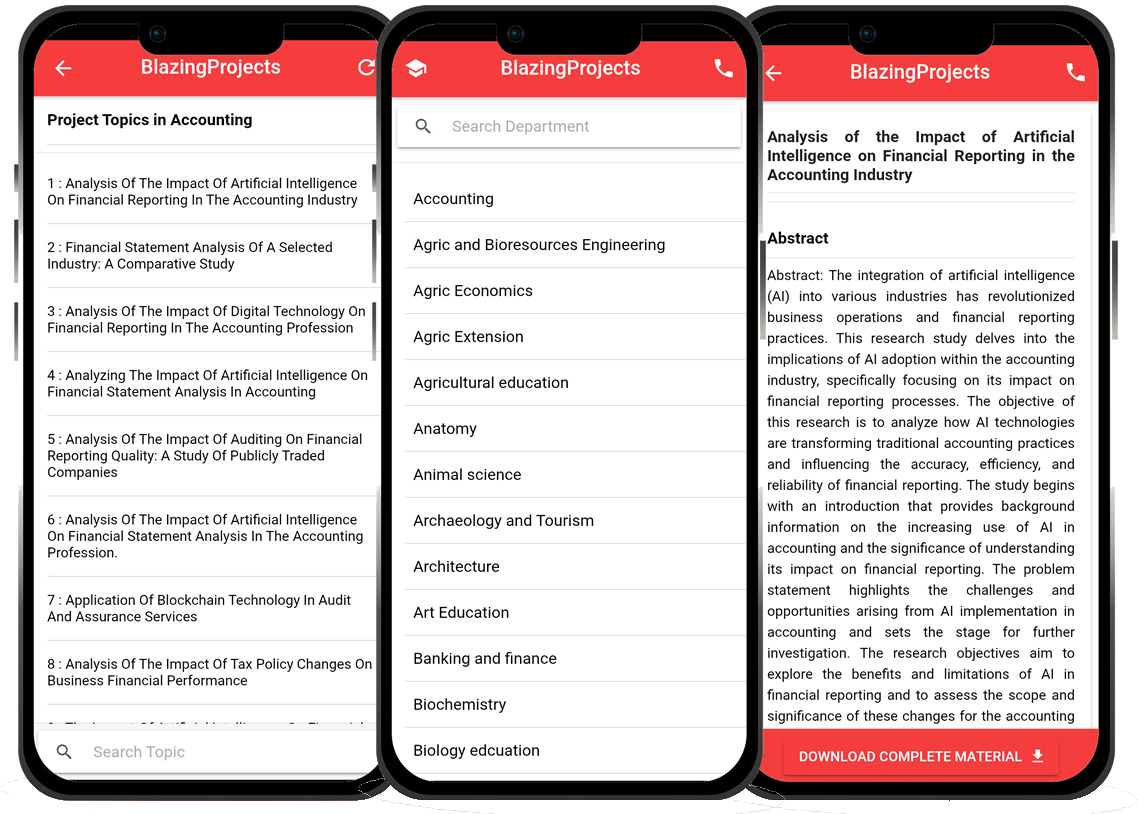

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Exploring the Impact of Archaeological Sites on Tourism Development: A Case Study...

The research project titled "Exploring the Impact of Archaeological Sites on Tourism Development: A Case Study" aims to investigate the relationship b...

Exploring the Impact of Archaeological Sites on Tourism Development: A Case Study...

The project topic, "Exploring the Impact of Archaeological Sites on Tourism Development: A Case Study," delves into the intricate relationship between...

The Impact of Archaeological Sites on Tourism Development in [Specific Region]...

The research project titled "The Impact of Archaeological Sites on Tourism Development in [Specific Region]" aims to investigate the significant relat...

The Impact of Archaeological Sites on Cultural Tourism Development: A Case Study...

The research project titled "The Impact of Archaeological Sites on Cultural Tourism Development: A Case Study" aims to investigate the significant rol...

Exploring the Impact of Archaeological Sites on Local Tourism Economies...

In the field of archaeology and tourism, the relationship between archaeological sites and local tourism economies is a topic of significant interest. This rese...

Exploring the Impact of Archaeological Discoveries on Tourism Development: A Case St...

The project topic, "Exploring the Impact of Archaeological Discoveries on Tourism Development: A Case Study," delves into the intersection of archaeol...

Exploring the Impact of Archaeological Sites on Tourism Development: A Case Study...

The project "Exploring the Impact of Archaeological Sites on Tourism Development: A Case Study" aims to investigate the relationship between archaeolo...

The Impact of Archaeological Sites on Tourism Development: A Case Study...

The project topic "The Impact of Archaeological Sites on Tourism Development: A Case Study" explores the intricate relationship between archaeological...

The Impact of Archaeological Sites on Cultural Tourism: A Case Study of [Specific Re...

The research project titled "The Impact of Archaeological Sites on Cultural Tourism: A Case Study of [Specific Region]" aims to explore the significan...