Comparative evaluation of grass, legume and their mixture with brewers' spent grains fed to west african dwarf rams

Table Of Contents

<p> </p><p>Title page – – – – – – – – – i</p><p>Certification – – – – – – – – – ii</p><p>Dedication – – – – – – – – – iii</p><p>Acknowledgement – – – – – – – – iv</p><p>Abstract – – – – – – – – – vi</p><p>Table of Contents – – – – – – – – vii</p><p>List of Tables – – – – – – – – – x </p><p><b>

Chapter ONE

: INTRODUCTION</b></p><p>1.1 Background of the Study – – – – – – – 1</p><p>1.2 Statement of Problem – – – – – – – 2</p><p>1.3 Objectives of the Study – – – – – – – 3</p><p>1.4 Justification of the Study – – – – – – – 3</p><p><b>Chapter TWO

: LITERATURE REVIEW </b></p><p>2.1 General Description of Sheep – – – – – – 4</p><p>2.2 Taxonomy of Sheep – – – – – – – 5</p><p>2.3 Sheep Production Statistics – – – – – – 5</p><p>2.4 Characteristics/Importance of Sheep – – – – – 7</p><p>2.4.1 Small Size – – – – – – – – 7</p><p>2.4.2 Reproductive efficiency – – – – – – <br>– 8</p><p>2.4.3 Feeding behavior – – – – – – – 8</p><p>2.4.4 Feed Utilization Efficiency – – – – – – 9</p><p>2.4.5 Fitness – – – – – – – – – 10</p><p>2.4.6 Socio-economic – – – – – – – – 10</p><p>2.5 Nutrient Requirements of Sheep – – – – – – 11</p><p>2.6 Factors Affecting Nutrient Requirements- – – – 14</p><p>2.7 Constraints and<br>Possible Remedies to Sheep Production- – – 16</p><p>2.7.1 Major constraints to ruminant production (Sheep<br>Production) – – 16</p><p>2.7.2 Remedies to Sheep production constraints – – – – 17</p><p>2.8 Digestibility- – – – – – – – – 17</p><p>2.8.1 Digestibility of mixed forages with BSG – – – – 18</p><p>2.8.2 Digestibility of grasses mixed with <i>Gliricidia sepium </i>– – -19</p><p>2.9 Estimating Digestibility of Fibre – – – – – – 19</p><p>2.9.1 Factors affecting fibre digestibility – – – – – – 20</p><p>2.10 Forages – – – – – – – – – 22</p><p>2.10.1 Grass forage – – – – – – – – 23</p><p>2.10.1.1 Guinea grass – – – – – – – – 23</p><p>2.10.1.2 Nutritional qualities of guinea grass- – – – – 24</p><p>2.10.2 Forage legumes – – – – – – – 25</p><p>2.10.2.1 <i>Gliricidia<br>sepium </i>– – – – – – -27</p><p>2.11 Brewer’ Spent<br>Grains (BSG) – – – – – – 28</p><p>2.11.1 Future Perspective of Brewers Spent Grains – – – – 29</p><p>2.11.2 Chemical Composition of Brewers’ Spent Grain – – – 29</p><p><b>Chapter THREE

:<br>MATERIALS AND METHODS</b></p><p>3.1 Experimental site – – – – – – – – 32</p><p>3.2 Experimental animals – – – – – – – 32</p><p>3.3 Experimental treatments – – – – – – – 32</p><p>3.4 Data collection – – – – – – – – 33</p><p>3.5 Experimental design – – – – – – – 34</p><p><b>Chapter FOUR

: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION</b></p><p>4.1 Proximate<br>Composition (% DM) of Forages and BSG – – 35</p><p>4.2 Proximate<br>Composition (% DM) of Faeces – – – – 37</p><p>4.3Voluntary and Nutrient<br>Intake of WAD sheep Fed</p><p><i> P. maximum</i>, <i>Gliricidia</i> and BSG- – – – – – 38</p><p>4.4 Digestibility of WAD Rams fed <i>P. maximum,</i></p><p><i>Gliricidia sepium</i> and BSG – – – – – – – 41</p><p>4.5Nitrogen Balance of<br>WAD rams fed <i>P. maximum,</i></p><p><i>Gliricidia sepium</i> and Brewers’ Spent Grains.<b> – – – </b>42</p><p><b>Chapter FIVE

:<br>CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION</b></p><p>5.1 Conclusion – – – – – – – – 44</p><p>5.3 Recommendation<br> – – – – – – – 44</p><p> References </p><p> Appendix</p><p><b>LIST OF TABLES</b></p><p>Table 1 Experimental Layout – – – – – 34</p><p>Table 2Proximate<br>Composition (% DM) of Forages and BSG- 36</p><p>Table 3 <br>Proximate Composition (% DM) of Faeces – – 38</p><p>Table 4Voluntary and<br>Nutrient Intake of WAD Sheep</p><p>Fed <i>P. maximum</i>,<br><i>Gliricidia</i> and BSG – – – 39</p><p>Table 5Digestibility of<br>WAD Rams Fed <i>P. maximum,</i></p><p><i>Gliricidia<br>sepium</i> and BSG – – – – 42</p><p>Table 6<br> Nitrogen Balance of WAD Rams<br>fed</p><p><i>P. maximum,<br>Gliricidia sepium</i> and Brewers’</p><p>Spent Grains – – – – – – 43</p> <br><p></p>Project Abstract

Four West African Dwarf sheep

were used to investigate the effect of brewers’ spent grains supplementation on

the utilization of mixed forage diets. The sheep were randomly assigned three

dietary treatments treatment 1- Gliricidia

sepium (G. sepium) + 200 g brewers’ spent grain (BSG), treatment 2- Panicum maximum (P. maximum) grass + 200 g BSG, and treatment 3- G. sepium (50%) + P. maximum (50%) + 200 g BSG, with four rams per treatment diet for

42 days. Data were collected on

feed intake and faeces voided during a digestibility trial. The results

revealed that animals fed on Treatment1 recorded the highest (p<0.05) total

dry matter intake (1626.83 g), total crude fibre intake (464.56 g), total

nitrogen free extract (846.35 g) and total organic matter intake (1563.69 g).

Animals on treatment 2 recorded the highest (p<0.05) total crude protein

intake (274.06 g) and total ether extract intake (73.19 g). Highest ash intake

was recorded in treatment 3 (76.65 g). Animals fed treatment 2 recorded the

highest digestibility % (P<0.05) in all nutrient parameters, while the least

was observed for those fed diet treatment 3. Animals fed treatment 2 utilized their diet efficiently

and which resulted in best digestibility while the least efficiency of

utilization was observed in animals on diet treatment 3. Results from this

study revealed that supplementation of forages with agro-industrial by-products

such as BSG enhances utilization of forages.

Project Overview

Inadequate feeding is a major limiting factor to small

ruminant production in tropical Africa (Ademosun, 2010). Fodder is of poor

nutritional value for most of the year due to the rainfall pattern. In the arid

and semi-arid zones, rainfall is less than 600 mm and between 600-1000 mm per

year, respectively. Many conventional diets for ruminants in the tropics are

poor quality roughages typified by high Neutral Detergent Fibre (NDF), low

nitrogen contents and slow fermentation rates. This poor dietary combination

leads to decreased intake, weight loss, increased susceptibility to health

risks and reduced reproductive performance. Including herbaceous legumes in

these feeding regimes helps to rectify some of the problems associated with low

protein and high fibre diets. Poppi and Mclennan, (1995) suggested that to

optimise the benefits of lablab as a feed source, it should be grazed in

conjunction with poor quality feedstuffs.

The quality of available forage is low and browse species

which can provide higher levels of proteins and carbohydrates are sparsely

dispersed. In the humid and sub-humid zones, up to six months of the year can

be rainless, resulting in poor quality forages. The rapid buildup of cell-wall

materials and decline in crude protein (CP) content with maturity reduces the

nutritional value of the forages. Little is known about the nutritional value,

distribution, palatability, seedling vigour and seasonal production of the

forage species that characterise the natural grassland. This is particularly

true of the arid, semi-arid and sub-humid areas which contain 75% of the sheep

and 80% of the goats of tropical Africa and where the rangeland is the most

important source of food (FAOSTAT, 2013). Besides the use of browse, other

strategies can be employed to improve the feeding of animals. During the dry

season, the quality of available herbage is so low that, unless the animals

have access to supplementary feeds, they lose weight. These supplementary feeds

can be obtained from agro-industrial by-products such as residues of oil

extracted from oil bearing seeds (groundnuts, coconut, palm kernels, cotton

seed, soyabean etc), by-products of grain processing (maize, rice, wheat,

sorghum, millet etc), peelings of crops (yams, cassava, potatoes, plantains

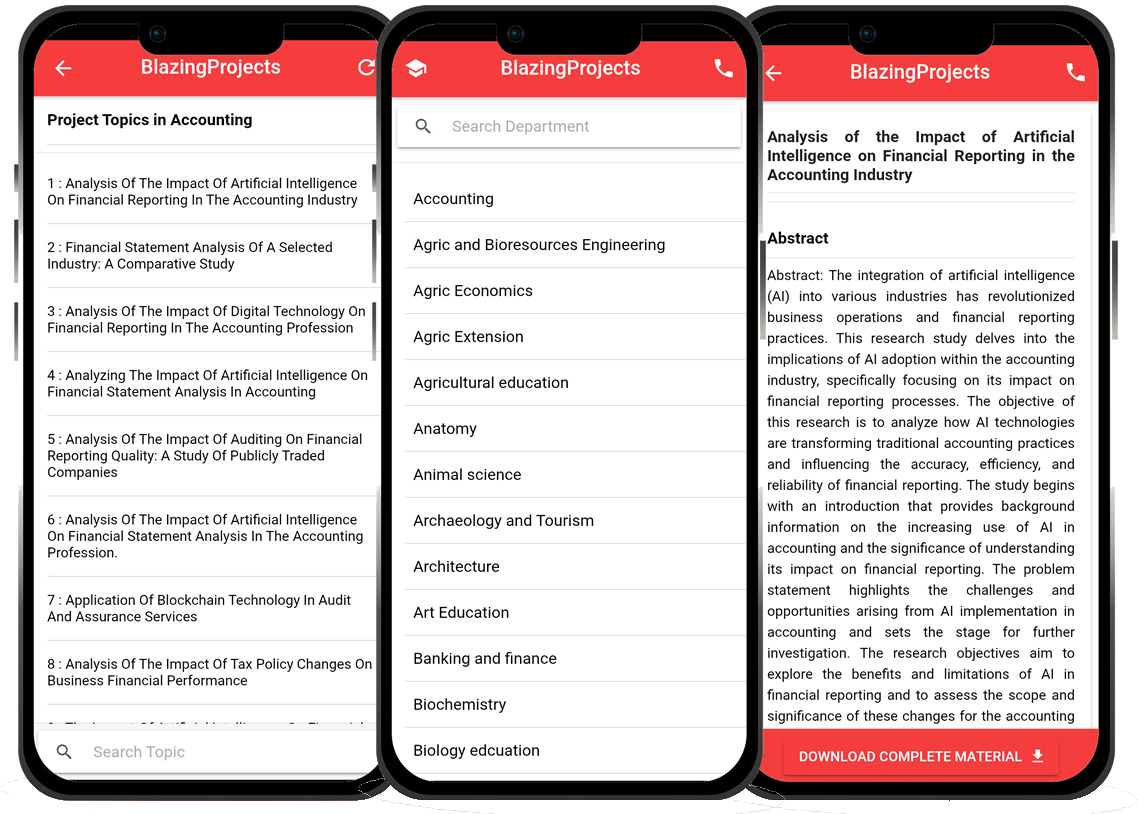

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities...

The project topic "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" focuses on the integration of mobile technolo...

Assessing the Impact of Mobile Technology on Agricultural Extension Services in Rura...

The project topic "Assessing the Impact of Mobile Technology on Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" aims to investigate the influenc...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services in Rural C...

The project topic, "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities," focuses on the application of mob...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Enhancing Agricultural Extension Services in Rural C...

The project topic, "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Enhancing Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities," focuses on the integration of mob...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improved Agricultural Extension Services...

The project topic, "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improved Agricultural Extension Services," focuses on leveraging the capabilities of mobile techno...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services in Rural C...

The project topic "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" focuses on the potential of mobile ...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services...

The project topic "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services" aims to explore the potential benefits and challenges as...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services in Rural C...

The project topic "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" focuses on the application of mobil...

Assessing the Impact of Mobile Technology on Agricultural Extension Services for Sma...

The project topic, "Assessing the Impact of Mobile Technology on Agricultural Extension Services for Smallholder Farmers," focuses on investigating ho...