Food security and agricultural development in times of high commodity prices

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Food Security2.2 Importance of Agricultural Development

2.3 Factors Influencing Commodity Prices

2.4 Global Food Security Challenges

2.5 Impact of High Commodity Prices on Agriculture

2.6 Government Policies and Food Security

2.7 Role of Technology in Agricultural Development

2.8 Sustainable Agriculture Practices

2.9 Food Distribution Systems

2.10 International Trade and Food Security

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Design3.2 Sampling Methods

3.3 Data Collection Techniques

3.4 Data Analysis Procedures

3.5 Ethical Considerations

3.6 Research Limitations

3.7 Research Validity and Reliability

3.8 Data Interpretation Methods

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Overview of Research Findings4.2 Impact of High Commodity Prices on Food Security

4.3 Agricultural Development Strategies

4.4 Policy Recommendations

4.5 Comparison of Findings with Existing Literature

4.6 Case Studies and Examples

4.7 Future Research Directions

4.8 Practical Implications of the Study

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Conclusion and Summary5.2 Summary of Findings

5.3 Implications for Policy and Practice

5.4 Contributions to the Field

5.5 Recommendations for Future Research

Project Abstract

ABSTRACT

Efforts to promote food security must distinguish between short-term and medium-term measures, but also between countries with agricultural potential and without such potential, argues this paper. Furthermore, while high international food prices provide appropriate incentives for agricultural development, it would be misguided to expect that they will automatically result in an increase of agricultural output. Globally, food security is both a demand-side and the supply-side challenge. High food prices make it more difficult to address food security on the demand-side, as more and more low-income households become unable to afford sufficient food, but at the same time, higher food prices can provide impetus to address food security on the supply-side, as more and more farmers may find it lucrative to increase agricultural production. However, not all countries can address both challenges simultaneously. In principle, a higher rate of food self-sufficiency can help to increase the food security of the local population. But efforts to boost food production are viable only in countries that have agricultural potential; in others such efforts bear great opportunity cost. Viable approaches to promote food security must recognize, this paper argues, that food security is not per se dependent on a country’s food trade balance. At the country level, food security does not depend on whether countries are able to cover domestic food consumption through domestic food production, but whether they are able to generate sufficient financial resources to finance necessary food imports. The same holds true at the household level. Hunger must be addressed through social policies, including food aid, in the short run, but it can sustainably be addressed only through higher household incomes in the medium run. Countries that do not have potential in agriculture will need to address food insecurity through the development of non-agricultural sectors, which generate more, and more productive and remunerative jobs, particularly for low-income households. By contrast, countries that have potential in agriculture would most suitably address food insecurity through economic development that includes the agricultural sector. Although higher international food prices can provide appropriate incentives for agricultural development, it should not be expected, the paper argues, that higher international food prices will automatically result in an increase of agricultural output. While desirable, this reaction is crucially dependent on two factors, namely (i) the pass-through of international commodity price changes to the farm gate; and (ii) the farmers’ capacity to raise production in response. In many developing countries, especially low-income countries, the pass-through to farm gates and the productive capacities of farmers, is insufficient, and therefore requires appropriate policies Abstract

Efforts to promote food security must distinguish between short-term and medium-term measures, but also between countries with agricultural potential and without such potential, argues this paper. Furthermore, while high international food prices provide appropriate incentives for agricultural development, it would be misguided to expect that they will automatically result in an increase of agricultural output. Globally, food security is both a demand-side and the supply-side challenge. High food prices make it more difficult to address food security on the demand-side, as more and more low-income households become unable to afford sufficient food, but at the same time, higher food prices can provide impetus to address food security on the supply-side, as more and more farmers may find it lucrative to increase agricultural production. However, not all countries can address both challenges simultaneously. In principle, a higher rate of food self-sufficiency can help to increase the food security of the local population. But efforts to boost food production are viable only in countries that have agricultural potential; in others such efforts bear great opportunity cost. Viable approaches to promote food security must recognize, this paper argues, that food security is not per se dependent on a country’s food trade balance. At the country level, food security does not depend on whether countries are able to cover domestic food consumption through domestic food production, but whether they are able to generate sufficient financial resources to finance necessary food imports. The same holds true at the household level. Hunger must be addressed through social policies, including food aid, in the short run, but it can sustainably be addressed only through higher household incomes in the medium run. Countries that do not have potential in agriculture will need to address food insecurity through the development of non-agricultural sectors, which generate more, and more productive and remunerative jobs, particularly for low-income households. By contrast, countries that have potential in agriculture would most suitably address food insecurity through economic development that includes the agricultural sector. Although higher international food prices can provide appropriate incentives for agricultural development, it should not be expected, the paper argues, that higher international food prices will automatically result in an increase of agricultural output. While desirable, this reaction is crucially dependent on two factors, namely (i) the pass-through of international commodity price changes to the farm gate; and (ii) the farmers’ capacity to raise production in response. In many developing countries, especially low-income countries, the pass-through to farm gates and the productive capacities of farmers, is insufficient, and therefore requires appropriate policies

Project Overview

Introduction

During the early years of their independence developing countries were exporting commodities; many developed countries specialized in manufactures. As commodity exporters, developing countries suffered from relatively volatile commodity prices in the short run and declining commodity prices over the long run. On the other hand, manufactured prices tended to increase. These developments were a major concern for developing countries and subsequently became an important focus of UNCTAD’s work. UNCTAD’s first Secretary-General, Raul Prebisch, as well as Hans Singer, have highlighted the negative implications of volatile and declining terms of trade for developing countries (Prebisch, 1960; Singer, 1950). Since the turn of the millennium however many commodity prices, including the prices of many agricultural produce, have increased substantially, while at the same time many manufactured prices, especially the prices of low-tech and low value added manufactures, have declined, effectively improving the terms of trade for the developing countries that continue to depend on commodity exports.1 This development prompted the Trade and Development Report 2005 (UNCTAD, 2005) to examine the question whether the reversal in barter terms of trade is likely to be a lasting phenomenon, which provides a historical opportunity for developing countries and encourages a rethinking of the classical development strategies that focused on promoting a gradual graduation from a commodity-dependent economy and an increasing specialization in manufactures. However, as the group of developing countries has become increasingly diverse during the past decades, there is no simple and uniform answer to this question. On the one side of the spectrum are relatively successful developing countries, especially in East and South-East Asia, which have increased their specialization in basic manufactures; on the other are many low-income countries, especially in Africa, which have maintained a strong specialization in primary commodities. Contrary to the latter, the former are negatively affected by the improving barter terms of trade. However, as highlighted by the Trade and Development Report 2005, countries in East and South-East Asia have more than compensated for declining unit values of their exports through a more than proportionate increase of their export volumes, resulting in a significant increase of their income terms of trade. By contrast, many countries in Africa have not been able to significantly increase their export volumes, despite increasing unit values of their exports, and have therefore seen only a small improvement of their purchasing power of exports. How economies react to changing barter terms of trade depends on whether the change of international commodity prices translates into a change of local producer prices, and whether economies have the productive capacities to react to such price changes.

Although the global financial crisis and economic slowdown have led to a marked decline of commodity prices since their peak in mid-2008, commodity prices are expected to remain elevated compared with historical trends, and especially compared with the late 1990s. And indeed many commodity prices have begun to rise again in recent months. Against this backdrop, this paper examines whether international commodity price hikes are a threat or an opportunity for developing countries. Such price hikes can, on the one hand, lead to rising food prices and undermine food security; but they can, on the other hand, also lead to rising farm gate prices and stimulate agricultural production. To evaluate the threats and opportunities that arise from higher levels of international food prices, this paper examines the pass-through of international food prices to both consumers and producers. Section B of this paper describes the recent increase of commodity prices; section C focuses on effects of commodity price hikes on consumers and producers; section D outlines the challenge of agricultural development in developing countries; and section E derives implications for policymakers.

The paper concludes that the prospect of high and sustained commodity prices provides indeed a historical opportunity for some of the poorest developing countries, many of which continue to be characterized by a strong dependence on commodities, to develop and benefit from the commodity economy. Yet, to minimize associated threats and size upon this opportunity is not an automatic process. To minimize threats, requires active social policies; to size opportunities demands active economic policies. The successful development of the agricultural sector ultimately necessitates that higher commodity prices are passed through to the farm gate (a question of appropriate incentives) and that farmers are capable of reacting to higher commodity prices (a question of productive capacities). To raise agricultural production and productivity, demands that available factors of production be more effectively and fully utilized, and that the linkages between the different economic sectors be strengthened. This critically depends on entrepreneurial capabilities, but also appropriate business support institutions and a functioning banking sector, which supplies credit that is suitable for investments in the real economy (Gore and Herrmann, 2008; UNCTAD, 2008a). Furthermore, developing countries must find ways to cope with short-term adjustment costs, including rising food prices which can undermine food security

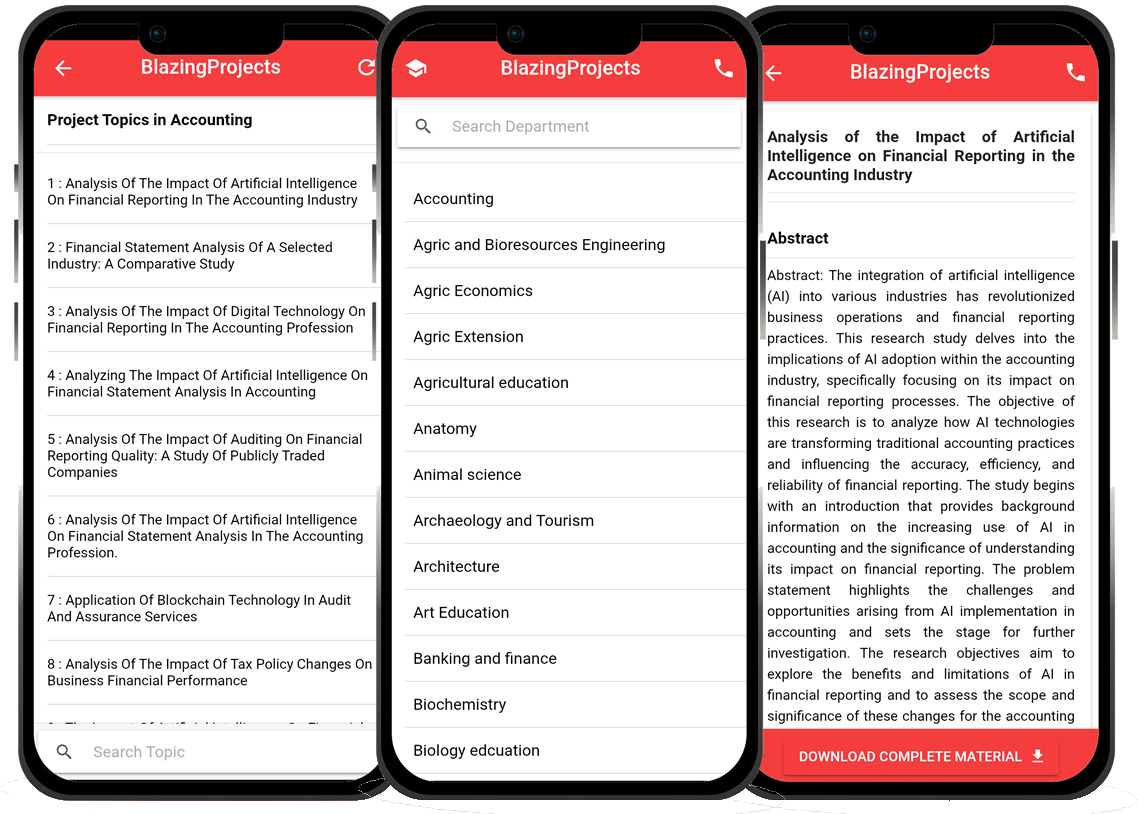

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities...

The project topic "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" focuses on the integration of mobile technolo...

Assessing the Impact of Mobile Technology on Agricultural Extension Services in Rura...

The project topic "Assessing the Impact of Mobile Technology on Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" aims to investigate the influenc...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services in Rural C...

The project topic, "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities," focuses on the application of mob...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Enhancing Agricultural Extension Services in Rural C...

The project topic, "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Enhancing Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities," focuses on the integration of mob...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improved Agricultural Extension Services...

The project topic, "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improved Agricultural Extension Services," focuses on leveraging the capabilities of mobile techno...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services in Rural C...

The project topic "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" focuses on the potential of mobile ...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services...

The project topic "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services" aims to explore the potential benefits and challenges as...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services in Rural C...

The project topic "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Improving Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" focuses on the application of mobil...

Assessing the Impact of Mobile Technology on Agricultural Extension Services for Sma...

The project topic, "Assessing the Impact of Mobile Technology on Agricultural Extension Services for Smallholder Farmers," focuses on investigating ho...