ECONOMICS OF SIZE IN IRRIGATED TOMATO (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill) PRODUCTION UNDER KANO RIVER IRRIGATION PROJECT (KRIP) PHASE I, KANO STATE, NIGERIA

Table Of Contents

<p> <b>TABLE OF CONTENTS </b></p><p><b>Content Page</b> </p><p><b>Title Page…………………………………………………………………........................................ i </b></p><p><b>Declaration ………………………………………………………………....…….........................… ii</b></p><p><b> Certification………………………………………………………………....................................... iii </b></p><p><b>Dedication…………………………………………………………………..…...........................…... iv</b></p><p><b> Acknowledgement…………………………………………………………. ..........................……... v </b></p><p><b>Table of Contents......................................................................................................................... vii </b></p><p><b>List of Tables………………………………………………………………. ….............................…... xi </b></p><p><b>List Figures..................................................................................................................................xii </b></p><p><b>List of Appendices……………………………………………………………............................…….xiii </b></p><p><b>Abstract………………………………………………………………………….............................…..xiv </b></p><p><b>

Chapter ONE

……………………………………………………….................................................1 </b></p><p>1.0 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………..........................................1 </p><p>1.1 Background to the Study…………………………………………………..................................…1 </p><p>1.2 Problem Statement…………………………………………………………....................................3 </p><p>1.3 Objectives of the Study…………………………………………………….................................….5 </p><p>1.4 Justification of the Study…………………………………………………..................................…..6 </p><p><b>Chapter TWO

………………………………………………………………….....….............................8 </b></p><p>2.0 LITERATURE REVIEW……………………………………….........................................................8 </p><p>2.1 Economic importance of tomato..................................................................................................8 </p><p>2.1.1 Tomato production in the study area…………..…………………...............................................9 </p><p>2.1.2 Irrigation and tomato production………………………………….................................................9 </p><p>2.1.3 Seasonality and price instability of tomato………………………………….................................11 </p><p>2.1.4 Farm size and productivity………………………………………….……...................................…11 </p><p>2.1.5 Patterns of farm size across countries and time……………………..................................….... 13 </p><p>2.1.6 Scale of production…………………………………………………………....................................13 </p><p>2.1.7 Concept of economics of size…………………………………….................................................14 </p><p>2.1.8 Economies of scale……………………………………………………….....…...............................15 </p><p>2.1.9 Concept of production efficiency in agricultural production………………..................................17 </p><p>2.1.10 Factors that affects efficiency……………………………………................................................19 </p><p>2.1.11 Effects of exogenous variables in the analysis of technical efficiency…..................................21 </p><p>2.1.12 Profitability analysis in crop production…………………………………................................….23 </p><p>2.2 Review of Analytical Tools……………………………………………….....…....................................24 </p><p>2.2.1 Descriptive statistics………………………………………………………....................................…24 </p><p>2.2.2 Budgeting techniques……………………………………………………....................................…..24 </p><p>2.2.3 Data envelopment analysis (DEA) approach to efficiency measurement….................................27 </p><p>2.2.4 Regression analysis……………………………………………...……...….................................…...33 </p><p>2.3 Review of empirical studies……………………………………..…………...........................................33 </p><p>2.3.1 Descriptive statistics/Budgeting techniques…………………….....................................................33 </p><p>2.3.2 Data envelopment analysis (DEA)…………………………………………...................................…35 </p><p><b>Chapter THREE

……………………………………………………….....................................................38 </b></p><p>3.0 METHODOLOGY…………………………………………………………..............................................38 </p><p>3.1 Description of the Study Area…………………………………….........................................................38 </p><p>3.2 Sampling Procedure and Sample Size…………………………………....................................………41 </p><p>3.2.1 Classification of the farm sizes……………………………………………....................................…...41 </p><p>3.3 Data Collection……………………………………………………...........................................................42</p><p>3.4 Analytical Techniques……………………………………………….............................................……….43 </p><p>3.4.1 Descriptive statistics………………………………………………….............................….................…43 </p><p>3.4.2 Budgeting techniques …………………………………………………...............................................….43 </p><p>3.4.3 A two-stage Data envelopment analysis………………………….......................................................46 </p><p>3.5 Measurement of Variables…………………………………………………......................................…...48 </p><p><b>Chapter FOUR

………………………………………………………….…….......................................…...51</b> </p><p>4.0 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION………………………………….........................................…..............51 </p><p>4.1 Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Irrigated Tomato Farmers………….................................….51 </p><p>4.1.1 Age distribution ….………………………………………………………....................................…….51 </p><p>4.1.2 Educational level……………………………………………………………...................................….52 </p><p>4.1.3 Farming experience………………………………………………………….................................….53 </p><p>4.1.4 Extension service…………………………………………………………................................…….53 </p><p>4.1.5 Farm size……………………………………………………………………...............................…..54 </p><p>4.1.6 Sources of finance…………………………………………………..………...............................….55 </p><p>4.2 Level of Inputs and Outputs in Irrigated Tomato Production Based on the Sizes of Production…55 </p><p>4.2.1 Land...........................................................................................................................................55 </p><p>4.2.2 Seed...........................................................................................................................................56 </p><p>4.2.3 Labour........................................................................................................................................56 </p><p>4.2.4 Fertilizer......................................................................................................................................57 </p><p>4.2.5 Pesticide.....................................................................................................................................57 </p><p>4.2.6 Tomato yield (supply level).......................................................................................................58 </p><p>4.3 Cost and returns analysis……………………...............................................................................60 </p><p>4.3.1 Gross returns...........................................................................................................................60 </p><p>4.3.2 Cost of production..................................................................................................................61 </p><p>4.3.3 Cost of seed..........................................................................................................................61 </p><p>4.3.4 Cost of fertilizer.....................................................................................................................61 </p><p>4.3.5 Labour costs........................................................................................................................61 </p><p>4.3.6 Pesticide costs....................................................................................................................61 </p><p>4.3.7 Cost of empty basket.........................................................................................................62 </p><p>4.3.8 Total variable cost.............................................................................................................62 </p><p>4.3.9 Total fixed costs...............................................................................................................62 </p><p>4.3.10 Gross Margin...............................................................................................................62 </p><p> 4.4 Estimate of Technical, Allocative and Economic Efficiencies Based on the three Sizes </p><p>of Production in the Study Area.............................................................................................64 </p><p>4.4.1 Estimate of technical efficiency based on the sizes of production in the study area…………………………………………….................................................................……...69 </p><p>4.4.2 Estimate of allocative efficiency based on the sizes of production in the study area…………………………………………….................................................................………70 </p><p>4.4.3 Estimate of economic efficiency based on the sizes of production in the study area…………………………………………………...............................................................….72 </p><p>4.4.4 Determinants of technical efficiency of irrigated tomato producing farms…………………………………………………….......................................................…...73 </p><p>4.5 Constraints to Irrigated Tomato Production in the Study Area………………....................77 </p><p><b>Chapter FIVE

…………………………………………………………………..........................80 </b></p><p>5.0 SUMMARY, CONCLUSION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS………..........................…..80 </p><p>5.1 Summary…………………………………………………………………….....................….80 </p><p>5.2 Conclusions…………………………………………………………………........................82 </p><p>5.3 Recommendations……………………………………………………….............................83 </p><p>5.4 Contribution to Knowledge…………………………………........... …………...................84 </p><p>REFERENCES……………………………………………….……………...................................86 </p>Project Abstract

ABSTRACT

The broad objective of the study was to examine the economics of size in irrigated tomato production under Kano river irrigation project (KRIP) phase I, Kano state, Nigeria. Primary data were collected from 213 irrigated tomato farmers, using multistage sampling techniques in three local government areas covered by KRIP. Data were collected during the 2014/2015 irrigation farming season using well-structured questionnaire. Data collected were analysed using descriptive statistics, budgeting techniques, two-stage data envelopment analysis (DEA) and regression models. The result indicates that majority (53%) of the irrigated tomato farmers were in their active years and approximately 57% had some form of formal education. Majority of the farmers( 93%) had been in tomato production for 8 to 31 years and 71% of the farmers had less than 1.0 hectare of farmland. Majority of farmers (78%) had no contact with extension workers while 76% used personal savings for production. It was found that only seed was over-utilised by medium and large scale farmers with average usage of seed above recommended rate resulting to output far below the potential yield of 40tonnes/ha. Irrigated tomato production was found to be profitable with an estimated total cost of ₦89,935.60/ha, ₦115,171.80/ha and ₦135,575.80/ha for small, medium and large farms respectively, and a gross margin of ₦135,040.90, ₦169,257.00 and ₦207,027.40 for small, medium and large farms respectively. The irrigated tomato production was profitable among the three sizes of production but more profitable in the large farms with the highest returns of 85 kobo for every ₦1 invested. The study found that most of the farms irrespective of size of holding have some technical inefficiency problems. The medium farmers, in terms of Constant Returns to Scale (CRS) and Variable Returns to Scale (VRS), had the best measures of technical efficiency 13.6% and 72.7% compared to 16.5% and 21.2% for small farms and 27.3% and 45.5% for large farms. Though large farms have been found efficient, with higher yields (6750kg/ha), it is the medium and large scale farms that emerged as farms with price-efficiency in terms of higher unit profit (0.43) respectively. Findings further revealed that none of the sampled irrigated tomato farmer reached the frontier threshold. However, the average economic efficiency of the irrigated tomato farms was 67%. The mean technical efficiency was 85%. This indicates that irrigated tomato farms were economically inefficient. Also, factors such as age, household size, farming experience, sources of finance, sex and cooperative society were responsible for 59% total variation in technical efficiency among the three categories of irrigated tomato farms. Majority of the irrigated tomato farmers complained of poor output price as the foremost constraint faced. It was therefore recommended that farmers should form a production clusters through the formation of producer groups or cooperatives with an advisory committee trained in various aspects of marketing to have access to up-dated pricing information and make it available to farmers on time this could improve their market intelligence and controlled irrigated tomato production per season.

Project Overview

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY

Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill) is an important vegetable crop in many parts of the world. It is one of the most important vegetables grown for its edible fruits in virtually every part of Nigeria. It is also one of the most widely cultivated crops in the world. It is an important source of vitamins and an important cash crop for small - holder and medium scale commercial farmers (Shankara et. al., 2005). The tomato fruit is an essential component of the diet of man and also an important industrial commodity (Jaliya et. al., 2007).

Egypt is the leading producer in Africa with the production of 8.5 million metric tonnes and Nigeria is the fourth in Africa and leads in West African sub region, with an estimated output of 1.10 metric tonnes and average yield of 10 metric tonnes per hectare. This is lower than average yield of 13.5 metric tonnes per hectare in tropical Africa and world average of 22.0 metric tonnes per hectare (FAO, 2010; Anons, 2010). The United States of America is the leading importer of fresh tomato (25% of the world output). Due to lower yield and expansion in consumer population in Nigeria, demand for tomato paste continues to grow, resulting in expanded import in to the country. According to Global Trade Atlas (GTA), Nigeria became Italy‟s second largest export market for tomato paste in 2003, with shipments value at $50 million dollars (Ewulo et. al., 2008).

There is no general definition on “scale” of enterprise in scientific literature. Different national and international institutions have their own definitions. The history of industrial revolution in developed and developing countries have shown that small and medium scale enterprises are the driving force of industrial development. The attentions of the national governments all over the world have, therefore focused on funding and supporting small and medium scale enterprise activities (Adamu, 2005). In Nigeria, small scale, resource poor farmers, the majority of who are engaged in subsistence or near subsistence farming produce the majority of aggregate agricultural output via rudimentary farming systems (Oviasogie, 2005; Ajibolade, 2005). Farm holdings across Nigeria are generally small with less than 5 hectares on average and are often inherited rather than purchased (Adeyemo et. al., 2010). Irrigated agriculture has played a major role in expanding the level of food production leading to the attainment of food self sufficiency and the overall agricultural development in many developing countries (Pierce, 1990; Ibabu et. al., 1996). In addition to reducing the uncertainty in yields of rain-fed crops due to climatic variability, it has also contributed to general increase in productivity of crops enabling the farmers to generate substantial income and to be gainfully employed all year round (Frederick, 1992). Today it is essential to note that Fadama farmers are responsible for supplying food to millions of people in Nigeria (Muhammad et al. 2011).

The major issues limiting agricultural productivity in Nigeria include low yields due to the use of low technology inputs, poor yielding seeds and livestock, lack of or poor adoption of improved production technologies, poor infrastructure, poor access to finance and poor marketing structures. Thus, to raise productivity and stimulate the sector, these problems need to be mitigated through adequate research and provision of technologies which would lead to competitive production (CBN, 2010). Increased output and productivity are directly related to production efficiency which arises from efficient input usage given the state of technology (Maurice, 2004). Increasing agricultural productivity requires one or more of the following: an increase in output with output increasing proportionately more than inputs; an increase in output while inputs remain the same; a decrease in both output and input with input decreasing more; or decreasing input while output remains the same (Adewuyi, 2002; Oni et. al., 2009). Production of vegetables is profitable; nevertheless is labour intensive. Thus, it provides income support especially to small farmers and employment opportunity for landless labourers in rural areas.

1.2 PROBLEM STATEMENT

In development economics, on-going debate on farm size and productivity “inverse relationship” (IR) exists. Before it was argued that small farm holdings were more efficient. However, the “inverse relation” was challenged with time (Maqbool et al. 2012).

Nigeria in her quest to be among the world 20 largest economy by the year 2020 has to fight poverty among its citizenry and empower them economically to collectively improve the economy of the nation. Despite the rapid pace of urbanization taking place in Nigeria, half of Nigerians (approximately 70 million individuals) still in rural areas; most of them engaged in small-holder semi-subsistence agriculture (Lenis et. al., 2011). Agriculture remains a crucial sector in the Nigerian economy, being a major source of raw materials, food and foreign exchange; employing over 70% of the Nigerian labour force and serving as a potential vehicle for diversifying the Nigerian economy.

However, there are no rigorous studies that explain productivity in this sector. Most small-holder farmers produce significantly below their frontiers. As a result, they produce less than optimal levels of output as revealed by studies (mostly land productivity) while many farming enterprises are profitable, profit margins are generally low (Lenis et. al., 2011). Profit maximization and maximum yield are common objectives of business enterprises and is grossly dependent on how best production resources are harnessed (Afolabi et. al., 2013).

Profitability in tomato production depends on how effectively a farmer can manage inputs costs in such a way that least cost is achieved without sacrificing production efficiency. Research findings have shown that some of the works have been done on small size farming with less or no comparison to medium and large sizes, especially in the production of vegetables like tomato under irrigated condition.

In 1980s agricultural production had become more diversified into high value commodities. Old cropping patterns had improved for example, from cereals to cash crop, from crop to horticulture and livestock products, in which small farms again started to gain comparative advantages over the large farms. Furthermore, big farms are input (fertilizer, agro chemicals etc) intensive that led to the degradation of their natural resource. Considering these externalities, large farms are no longer in lead in productivity and efficiency as compared to small farms (Maqbool et. al., 2012). Therefore, there is the need to assess the economics of size in irrigated tomato production in term of small farm size, medium and large size to see which of the sizes give higher productivity and more profit than the other in Kano River Irrigation Project (KRIP).

Based on this background, the following research questions were addressed by the study:

i) What are the socio-economic characteristics of farmers in the study area?

ii) What are the levels of inputs and outputs in irrigated tomato production based on the sizes of production in the study area?

iii) What are the costs and returns associated with irrigated tomato production based on the sizes of production?

iv) What are the technical, allocative and economic efficiencies in irrigated tomato production based on sizes of production in the study area?

v) What are the constraints being faced by irrigated tomato producers in the study area?

1.3 OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY

The broad objective of the study in the study area was to examine the Economics of Size in Irrigated Tomato Production under Kano River Irrigation Project (KRIP), Nigeria. More specifically the study achieved the following objectives:

i) describe the socio-economic characteristics of farmers in the study area.

ii) describe the levels of inputs and outputs in irrigated tomato production based on the sizes of production in the study area.

iii) determine the costs and returns in irrigated tomato production based on the sizes of production in the study area.

iv) estimate the technical, allocative and economic efficiencies based on the sizes of production in the study area.

v). identify and describe the constraints to irrigated tomato production in the study area.

1.4 JUSTIFICATION THE STUDY

Africa is the only developing region where crop output and factor productivity growth are lagging seriously behind population growth (Byiringiro, 1996). The inverse relationship between size of land holding and agricultural productivity has taken an important place in the literature of agricultural economics and agricultural development in recent decades. For various reasons farmers face different productivities of inputs as the size of their holding vary and thus, making their output/input ratios vary systematically with the size of their farms. The debate persists because no fully agreed upon consensus has yet emerged on what is the exact implication of the observed relationship and because of the possible (and sensitive) policy implication that is engenders (Bardhan, 1973; Barrett, 1994). For example, if it is due to a higher efficiency of small farms (low opportunity cost of labour, decreasing returns to scale), then addressing issues of land reform would be the straight forward implication. However, if it is a consequence of imperfect factor markets (smaller farms confront different factor prices from larger farms i.e smaller farms face a low opportunity cost of labour and high prices of land and capital which is an inverse pattern for that of larger farms) then attention should be directed toward the institutional framework and the functioning of the rural economy.

In the face of the scarcity of farmland and constraints of extensive farming, the significance of increasing productivity may not be taken too lightly. Higher agricultural productivity will lead to quicker growth, rural jobs and resources for industrial progress along with food supply to ever-increasing population. As a consequence, raising agricultural productivity is an important policy goal for concerned governments and development agencies.

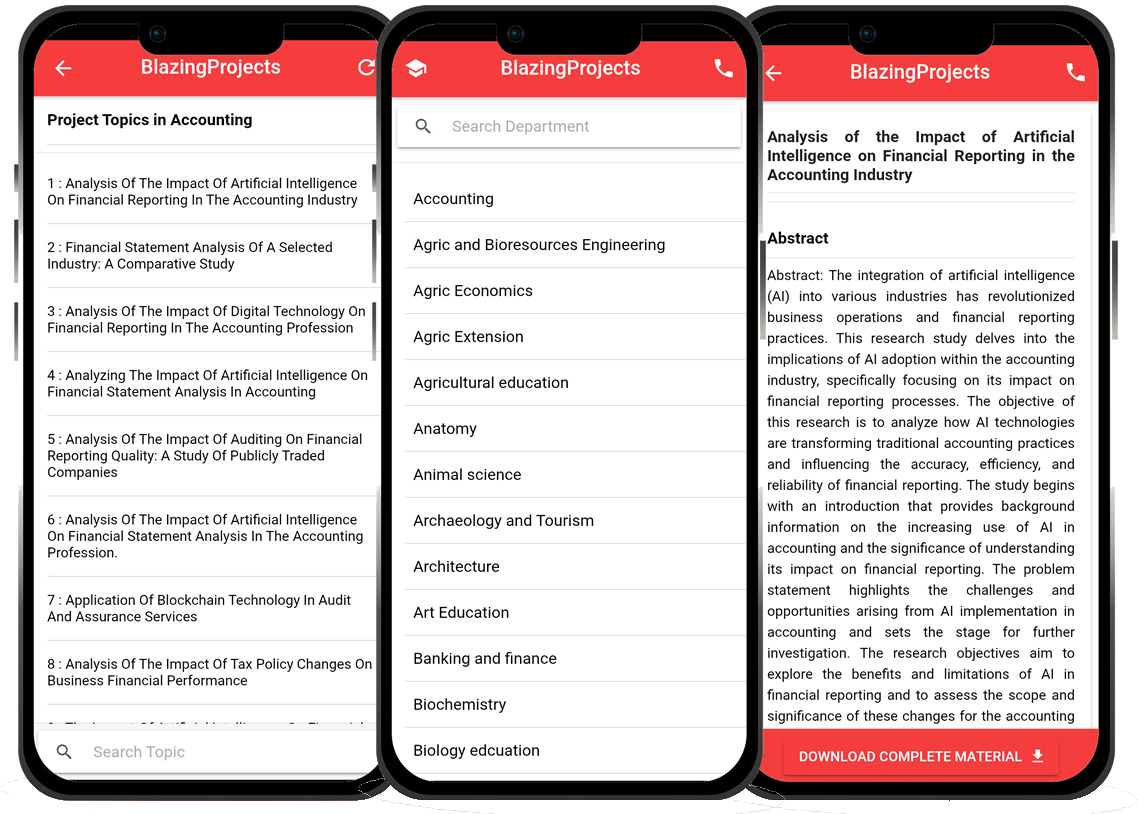

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Analysis of the impact of climate change on agricultural productivity and food secur...

The research project titled "Analysis of the impact of climate change on agricultural productivity and food security in a selected region" aims to inv...

Analyzing the Economic Impacts of Climate Change on Crop Production in Developing Co...

The research project titled "Analyzing the Economic Impacts of Climate Change on Crop Production in Developing Countries" aims to investigate the effe...

Analyzing the Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity and Food Securit...

The research project titled "Analyzing the Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity and Food Security in Developing Countries: A Case Study of...

The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallhold...

The project topic "The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallholder Farmers in a Developing Country" delves into...

Assessment of the Economic Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Production in a ...

The project titled "Assessment of the Economic Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Production in a Specific Region" aims to investigate the effec...

The impact of climate change on agricultural productivity: A case study of smallhold...

The impact of climate change on agricultural productivity is a critical issue affecting smallholder farmers in developing countries. Climate change poses signif...

The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallhold...

The research project titled "The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallholder Farmers in a Developing Country" a...

Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selec...

The research project titled "Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selected Region" aims to investigate the r...

Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selec...

The research project titled "Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selected Region" aims to investigate the p...