AGRICULTURAL PUBLIC SPENDING IN NIGERIA

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of study

1.5 Limitation of study

1.6 Scope of study

1.7 Significance of study

1.8 Structure of the research

1.9 Definition of terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Agricultural Public Spending2.2 Historical Perspectives

2.3 Economic Impact of Agricultural Public Spending

2.4 Agricultural Policies and Public Spending

2.5 International Comparisons

2.6 Challenges in Agricultural Public Spending

2.7 Innovations in Agricultural Public Spending

2.8 Future Trends in Agricultural Public Spending

2.9 Case Studies

2.10 Summary of Literature Review

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Methodology Overview3.2 Research Design

3.3 Data Collection Methods

3.4 Sampling Techniques

3.5 Data Analysis Procedures

3.6 Ethical Considerations

3.7 Limitations of the Research Methodology

3.8 Research Validity and Reliability

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Data Analysis and Interpretation4.2 Descriptive Statistics

4.3 Inferential Statistics

4.4 Comparison of Findings with Literature Review

4.5 Discussion on Research Findings

4.6 Implications of Findings

4.7 Recommendations for Future Research

4.8 Practical Implications

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Findings5.2 Conclusion

5.3 Contributions to Knowledge

5.4 Practical Applications

5.5 Recommendations for Policy and Practice

Project Abstract

ABSTRACT

Public spending on agriculture in Nigeria is exceedingly low. Less than 2 percent of total federal expenditure was allotted to agriculture during 2001 to 2005, far lower than spending in other key sectors such as education, health, and water. This spending contrasts dramatically with the sector’s importance in the Nigerian economy and the policy emphasis on diversifying away from oil, and falls well below the 10 percent goal set by African leaders in the 2003 Maputo agreement. Nigeria also falls far behind in agricultural expenditure by international standards, even when accounting for the relationship between agricultural expenditures and national income. The spending that is extant is highly concentrated in a few areas. Three out of 179 programs account for more than 81 percent of federal capital spending, of which nearly three-quarters go to government purchase of agricultural inputs and agricultural outputs alone. The analysis finds that many of the Presidential Initiatives—which differ greatly in target crops, technologies, research, seed multiplication, and distribution—have identical budgetary provisions. This pattern suggests that the needs assessment and costing for these initiatives may have been inadequate, and that decisions may have been based on political considerations rather than economic assessment. Budget execution is also poor. The Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) best practice standard for budget execution is no more than 3 percent discrepancy between budgeted and actual expenditures. In contrast, during the period covered by the study, the Nigerian federal budget execution averaged only 79 percent, meaning 21 percent of the approved budget was never spent. Budget execution at the state and local levels was even less impressive, ranging from 71 percent to 44 percent. However, other sectors showed similar low levels of budget execution, suggesting that the problem is a general one going beyond agriculture. There is an urgent need to improve internal systems for tracking, recording, and disseminating information about public spending in the agriculture sector. Consolidated and up-to-date expenditure data are not available within the Ministry of Agriculture, not even for its own use. Without this information, authorities cannot undertake empirically-based policy analysis, program planning, and impact assessment. There is also a need for clarification of the roles of the three tiers of government in agricultural services delivery. This is important to reduce overlaps and gaps in agricultural interventions and improve efficiency and effectiveness of public investments and service delivery in the sector. Finally, applied research is needed to address critical knowledge gaps in several areas (i) Spending on fertilizer programs makes up a sizeable portion of overall agricultural spending in Nigeria, yet very little is known about the impact of this spending. (ii) To date, only a small portion of the national grain storage system has been constructed, but if the entire network is completed as planned, the cost will be enormous. Supporting even the current modest level of grain marketing activities is consuming significant amounts of public resources. Is an investment on this order of magnitude desirable? What has been the impact of these investments? (iii) There is a need for an analytical study focusing on the economics of the National Special Program for Food Security (NSPFS). The total cost of NSPFS II is estimated at US$364 million. Detailed financial information about the NSPFS is not publicly available, however, making it difficult to assess whether the considerable investment in NSPFS I generated attractive returns, and whether NSPFS II merits support as currently designed. A rigorous external evaluation is needed to assess the performance of NPSFS and generate information that could be used to make design adjustments. Keywords agriculture, public spending, expenditure policy, Nigeria, Kaduna, Cross River, Bauchi

Project Overview

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Objectives of the Study

The potential contribution of agriculture to economic development in Nigeria is discussed in two important government policy documents: (i) the National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS), and (ii) the New Agricultural Policy Thrust (NAP). NEEDS, implemented in 2004 as Nigeria’s homegrown poverty reduction strategy, emphasizes the importance of increasing agricultural production and safeguarding food security as the country pursues its overarching goal of diversifying the economy away from oil (NPC 2004).1 • How much is being spent on agriculture, and how is spending distributed across the three tiers of government (federal, state, and local)? NAP, adopted in 2001 and modified two years later, does not present a detailed action plan but articulates a vision of how agriculture can become an engine of growth and poverty reduction, identifies binding constraints to the realization of that vision, and proposes policies to overcome those constraints (FMARD 2001). The strong emphasis in NEEDS and NAP on agricultural growth shows that agriculture is attracting renewed attention in the national development agenda of Nigeria. But strategies and policies alone will not be sufficient to transform Nigerian agriculture into a dynamic engine of pro-poor growth. Strategies and policies will have little impact unless they can be translated into an implementable action plan that is supported by legislative action and backed up by appropriate public expenditure. With Nigeria’s agricultural sector continuing to underperform relative to the ambitious targets set by government, hard questions are being asked about the quantity and quality of public expenditure in agriculture, as well as about the appropriateness of the institutional environment in which public expenditure decisions are made. Answering those questions will require a thorough understanding of public-spending patterns and trends in Nigerian agriculture.

This paper seeks to achieve four main objectives: establish a robust database on public expenditure in the agricultural sector; diagnose the level and composition of agricultural expenditure in the recent past; understand the budget processes that determine resource allocation in the sector; and draw preliminary policy recommendations for improving the efficiency of public expenditure in the agricultural sector. Understanding the pattern of public spending in a sector and the process through which spending decisions are made usually lies at the heart of any public expenditure review. Further analysis, which would extend a public expenditure review to examine not only the quantity and quality of spending but also its efficiency and impact, would add an important layer of knowledge that can contribute to policy decision making. The scope of the study was restricted because preliminary investigations revealed that assembling and validating core expenditure data in Nigeria represented a major challenge in and of itself. It therefore seemed prudent not to set out an overly ambitious set of objectives, the realization of which might be compromised by a lack of data. This paper thus should be viewed as a preliminary analytical exercise designed to address basic questions about public expenditure in the agriculture sector. Those include the following:

• In what areas (subsectors, programs, and projects) are public expenditures in support of agriculture being made?

• How are decisions on public expenditures in support of agriculture made, and by whom?

• What recommendations can be made to support a more effective and efficient use of public funds for agriculture?

1.2 Methodology and Approach

1.2.1 Geographical Coverage

State and local governments account for about 46 percent of all public expenditure in Nigeria. The proportion is thought to be even higher in the agricultural sector (World Bank 2007a). To analyze expenditure in a sector in which subnational governments are known to play a large role, it is necessary to go beyond the federal budget and examine also spending by the lower tiers of government. Because data on subnational expenditure in specific sectors including agriculture are not readily available from a central source, data on state and local government expenditure must be collected at the state and local government area (LGA) levels. Resource constraints ruled out the possibility of collecting data from a large number of states and LGAs, so a case study approach was used. Three states and three LGAs were selected for in-depth analysis. The states consist of Bauchi, Cross River, and Kaduna. Selection of the states was based on the following considerations:

(i) high importance of agriculture in the economy of the state;

(ii) capacity within the state-level public institutions to provide information and data;

(iii) expressed interest in collaborating with the research team; and

(iv) location in different geopolitical zones.

The LGAs consist of Dass, Odukpani, and Birnin Gwari. Selection of the LGAs, one of which was located in each of the case study states, was based on criteria similar to those used for the selection of states.

1.2.2 Time Frame

The core analysis of federal-, state-, and LGA-level expenditures covers the period 2001 to 2005. The original study design called for a longer period of coverage, but the time frame was shortened after it became apparent that few data are available for years prior to 2000, especially at the LGA level. Nevertheless, the overview of the agricultural sector in Nigeria presented in Chapter 2, which draws on analysis done by International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the World Bank as well as other organizations, takes a much longer view and provides some historical perspective of agricultural sector performance.

1.2.3 Definition of Agricultural Spending

The first challenge was to define exactly what is meant by the term agricultural spending. After considering various definitions, the team decided to use a fairly restrictive definition: this study would review public spending in agriculture, as opposed to public spending for agriculture. Use of a restrictive definition was deemed appropriate for two reasons. First, given time and funding constraints, it seemed preferable to analyze a limited number of key topics in depth, rather than covering a large number of topics superficially. Second, public spending in other sectors was recently reviewed through several other studies, most notably the Public Expenditure Management and Financial Accountability Review (World Bank 2007a), so there was a need to avoid duplication of effort. The next challenge was how to operationalize the term in agriculture. In defining agricultural expenditure categories, the authors were guided by three considerations: (i) commonly used definitions of agricultural spending found in the literature; (ii) the expenditure responsibilities of the federal and state ministries of agriculture in Nigeria; and (iii) the structure of the Nigerian government’s budget and expenditure accounts. The definitions of agricultural spending commonly found in the literature merit consideration because they reflect widely held views about the types of expenditures that most directly affect agricultural activity. The expenditure responsibilities of federal and state ministries of agriculture in Nigeria merit consideration because they provide obvious entry points for policy discussions. The structure of Nigeria’s budget and expenditure accounts merits consideration for practical reasons, because the structure of the budget and expenditure accounts determines what data can be analyzed, and how. Based on these three considerations, agriculture was defined to include the following expenditure categories: agricultural research, agricultural extension and training, agricultural marketing, agricultural input supply and subsidization (seed, fertilizer, crop chemicals, etc.), crop development, livestock development, fisheries, irrigation (to the extent that it is undertaken by federal and state ministries of agriculture and local departments of agriculture), and food security. Forestry and wildlife were initially considered for inclusion, but in the end they were not included because in Nigeria investments in those subsectors take place outside of the federal and state ministries of agriculture, meaning that an entirely separate data collection effort would have been necessary.

1.3 Data Sources and Challenges

The public expenditure data used here were obtained from ministries of agriculture, other key ministries and agencies (e.g., those responsible for finance, budget, local government, etc.), and agriculture-focused parastatals, all operating at the federal, state, or local government level. In addition, other public finance data were used (e.g., revenue data), as well as public expenditure data from other sectors. The core data set included both budgeted and actual expenditures, classified where feasible along economic, programmatic, sectoral, and functional lines.

Most public expenditure reviews are hampered by data problems, and this undertaking was no exception. Despite repeated efforts, it was not possible to obtain a complete and detailed breakdown of agricultural expenditure by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture.2 An important lesson learned from this experience is that public expenditure work focusing on the agriculture sector of Nigeria faces four major data challenges (see also Appendix A for more detail on this issue):

(1) Agricultural expenditure data obtained from different sources in Nigeria are inconsistent. For example, disaggregated expenditure data provided by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture do not correspond with federal expenditure data available from the Office of the Accountant General of the Federation (OAGF). The discrepancy is puzzling, because the OAGF database is ostensibly prepared based on transcripts provided by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture. Because of the inconsistencies between the two data sets, the analysis of the structure of federal agricultural spending presented in this paper is based exclusively on data provided by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture. Also because of the inconsistencies between the two data sets, the figures used to analyze the structure of agricultural spending differ in many respects from the figures used to analyze the magnitude of agricultural spending. An important lesson learned from this experience is that public expenditure work focusing on the agriculture sector of Nigeria faces four major data challenges (see also Appendix A for more detail on this issue):

(2) For some years, it is unclear what constituted the official government budget. The confusion stems from past disagreements between the executive and the legislature. During the early 2000s, on several occasions the executive was reluctant to implement the budget approved by the legislature because it contained huge funding increases compared with the proposals made by the executive. The executive feared that implementing such inflated budgets would lead to overheating of the economy, so it revised downward the budgets received from the legislature. From 2001 to 2003, it is not clear whether the budgets approved by the legislature were the inflated versions or the revised versions, so for those years it is not certain what constituted the approved budget.

(3) Many recurrent costs (especially operational costs) are misclassified in government accounts as capital spending. This problem goes beyond the agricultural sector and derives from problems inherent in the broader budget system. Over time in Nigeria, officials have come to appreciate the relative lack of control they have over much recurrent spending and the relatively greater influence they exercise over capital spending. Once departments are able to “push” an item through the budget as a capital spending item, then assuming the funding is approved, they can effectively control disbursement. This leads to widespread deliberate misclassification of recurrent spending items as capital spending items (see World Bank 2007a for more details). Because the extent of the problem is difficult to assess, the authors were unable to undertake a proper analysis of the breakdown of agricultural spending in terms of economic classification.

(4) Off-budget expenditures and donor-provided funds are inadequately documented. These two categories of spending overlap extensively, because a substantial share of donor-provided funds is not captured in government accounts and therefore remains “off-budget.” Reliable data on these two categories are extremely difficult to obtain. Appendix B presents an incomplete listing of recent donor-funded programs and projects in the areas of agricultural development, land administration, and water resources management. It is not clear what portion, if any, of the resources spent under each project listed in Appendix B is already captured in standard government accounts. To avoid possible double-counting, the incomplete data on donor-funded programs and projects in the agricultural sector were not included with the government data on public spending in agriculture.

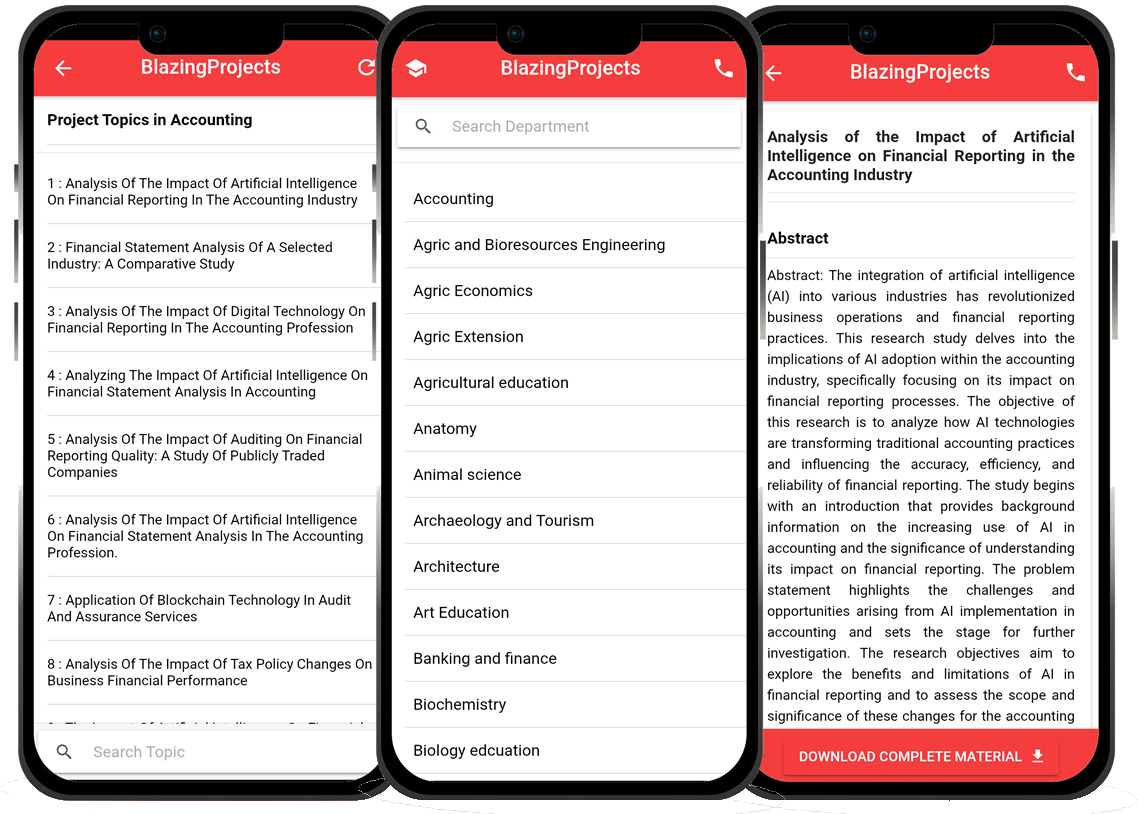

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Analysis of the impact of climate change on agricultural productivity and food secur...

The research project titled "Analysis of the impact of climate change on agricultural productivity and food security in a selected region" aims to inv...

Analyzing the Economic Impacts of Climate Change on Crop Production in Developing Co...

The research project titled "Analyzing the Economic Impacts of Climate Change on Crop Production in Developing Countries" aims to investigate the effe...

Analyzing the Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity and Food Securit...

The research project titled "Analyzing the Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity and Food Security in Developing Countries: A Case Study of...

The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallhold...

The project topic "The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallholder Farmers in a Developing Country" delves into...

Assessment of the Economic Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Production in a ...

The project titled "Assessment of the Economic Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Production in a Specific Region" aims to investigate the effec...

The impact of climate change on agricultural productivity: A case study of smallhold...

The impact of climate change on agricultural productivity is a critical issue affecting smallholder farmers in developing countries. Climate change poses signif...

The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallhold...

The research project titled "The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallholder Farmers in a Developing Country" a...

Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selec...

The research project titled "Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selected Region" aims to investigate the r...

Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selec...

The research project titled "Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selected Region" aims to investigate the p...