INFLUENCE OF PRICES ON MARKET PARTICIPATION DECISIONS OF INDIGENOUS POULTRY FARMERS IN FOUR DISTRICTS OF EASTERN PROVINCE, KENYA

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction 1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Prices in Agricultural Markets 2.2 Market Participation Decisions of Farmers

2.3 Factors Influencing Market Participation

2.4 Economic Theories on Price Influence

2.5 Previous Studies on Market Participation

2.6 Price Volatility in Agricultural Markets

2.7 Impact of Prices on Farmer Decision Making

2.8 Marketing Strategies in Response to Price Changes

2.9 Price Information and Market Efficiency

2.10 Technology and Market Access for Farmers

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Methodology Overview 3.2 Research Design and Approach

3.3 Sampling Techniques and Sample Size

3.4 Data Collection Methods

3.5 Data Analysis Techniques

3.6 Ethical Considerations

3.7 Validity and Reliability

3.8 Limitations of the Research Methodology

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Overview of Research Findings 4.2 Analysis of Market Participation Decisions

4.3 Impact of Prices on Farmers' Behavior

4.4 Relationship Between Price and Market Access

4.5 Strategies Adopted by Farmers in Response to Price Changes

4.6 Market Efficiency and Price Information

4.7 Technology Adoption and Market Integration

4.8 Comparison with Previous Studies

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Research Findings 5.2 Conclusion

5.3 Implications for Policy and Practice

5.4 Recommendations for Future Research

5.5 Contributions to the Field

Project Abstract

ABSTRACT

Over 70% of the domesticated birds in Kenya are indigenous chicken (IC) providing meat and table eggs. They are frequently raised through the free range, backyard production system. Small flock sizes are characteristic of this production system and often, sales are mainly at the farmgate. Although IC production possesses enormous potential at livelihood improvement, marketing systems are undefined and variable. The influence of prices on market engagement has frequently been assumed. A study of 68 farmers conducted in Machakos, Kibwezi, Nzaui and Mwala District in 2008 revealed that 70% of all IC sales were conducted at the farmgate while only 19% of the sales were at the local market. This study also investigates the probability of market participation by employing a binary logistic regression model. The results suggests that while farmers complain of poor farm gate prices for indigenous chicken offered by middlemen, low volumes are an important drawback to market participation. Keywords Market, Price, Indigenous chicken, Farm-gate

Project Overview

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY

There are an estimated 29 million birds in Kenya with Indigenous Chicken (IC) being 70% of this number. Indigenous poultry production in Kenya is an important activity for 75% of the Kenyan population and these birds are mostly kept for domestic consumption and sale. The numbers kept vary with location but are largely reared under the free range system which is estimated to be more profitable (Menge, Kosgey & Kahi, 2007) than keeping indigenous poultry under confinement. However, these birds need extra feed to supplement that obtained from their scavenging activity (Kingori, Tuitoek, Muiruri, Wachira & Birech, 2007). Usually, these flocks are small and external inputs few (Okitoi, Udo, Mukisira, De Jong & Kwakkel, 2006). For instance, Sørensen (2007) puts the flock sizes in Makueni at between 20-30, while for Western province they are estimated as between 7-10 birds (Waithaka, Nyangaga, Staal, Wokabi, Njubi, Muriuki, et.al,. 2002) while Okitoi et.al., (2006) put this figure at 10-20 birds. These figures are against a national average of 13 birds per household (Nyaga, 2007). In Uganda, the size varies anywhere between 17-22 birds (Illango, Etoori, Olupot & Mabonga, 2002; Ssewannyana, Onyait, Ogwal & Masaba, 2006) while in Morocco, these are 11 chicken per household (Benabdeljelil, Arfaoui & Johnston, 2001) and between 15-20 birds in Botswana (Badubi, Rakereng & Marumo, 2006). IC in Nigeria, as in many parts of Africa are an important income source especially for rural women (Alabi, Esobhawan & Aruna, 2006, Akinola & George, 2008). Small flock sizes may however not be very attractive especially in terms of market efficiency as has been reported in Malawi where farmers’ market participation decision is not significantly influenced by prices but is ad hoc depending on the farmers needs at any particular point in time (Gausi, Safalaoh, Banda & Ng'ong'ola, 2004). The marketing system for indigenous birds in Kenya is described as unorganised, weak and indeterminate (Mathuva 2005, Munyasi, Nzioka, Kabiru, Wachira, Mwangi, Kaguthi et.al., 2009). In Uganda, many farmers do not assess market conditions before embarking on production (Alum, Kanzikwera & Sanginga, 2007) a scenario that is probably replicated in Kenya.

This may partly explain why production is still low despite the existence of an unmet demand for poultry meat estimated at 12.4kg per adult equivalent in the urban areas (Gamba, Kariuki & Gathigi, 2005) and projected to grow to 29,600MT by 2014 (Muthee, 2006). It would be expected that with properly functioning markets, farmers should scale production and therefore supply, to reflect market trends.

However, supply will be responsive only after farmers make the decision to participate in the market, decisions conditioned by several factors. There are very few empirical studies showing the association between these indices and the decision to sell IC in particular since many farmers sell to avoid major losses from disease. For the IC sector, two market channels are available to farmers viz, at the farmgate, or at the market. IC prices are usually spot prices with prices varying by season, chicken sex, size and trader (Munyasi et.al, 2009), but rarely are the birds weighed just as reported for many African countries (Guèye, 2001). Traders usually buy IC from farmers in the rural markets and assemble these for subsequent sale in larger urban markets. A Value Chain analysis for IC in Kilifi and Kwale reports the main reasons cited for the decision by farmers to sell are the need to offload in anticipation of disease outbreaks and to earn some income to cater for household requirements. The major disease causing mortalities in flocks is New Castle Disease (NCD). In Western Kenya, reducing mortality in chicken through NCD vaccination by 1% was shown to increase offtake by 0.11% (Okitoi, et.al, 2006). In Uganda, IC flock sizes were shown to increase by 195% following crossbreeding and NCD vaccinations, the latter reducing mortalities by 86% (Ssewannyana, et.al., 2006).

In Kenya, many IC farmers complain of low profits as they point an accusing finger towards exploitative middlemen (Nyange, 2000). Prices offered to IC farmers are low at about 18% of the terminal price in Coastal Kenya while in other countries IC farmers appear to receive fairly higher returns (see for instance Mlozi, Kakengi, Minga, Mtambo & Olsen, 2003, Gondwe, Wollny & Kaumbata, 2005). Munyasi et.al. (2009) report disease and price fluctuations in the larger Machakos and Makueni districts to be the major challenges in the marketing of IC from the perspective of traders. With an uncertain price structure, it is not clear whether farmers on the other hand respond to market information. This paper therefore explores the prices offered farmers for IC and distance to markets and their influence on the decision to participate in the market by poultry farmers.

1.2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

1.2.1 Data collection and general description of study area

To study these relationships, we use baseline data collected from farmers; all members of IC common interest groups (CIGs) who received training from service providers on main aspects of poultry management viz; housing, feeding, disease control and marketing between August and September 2008. The farmers were located in 8 divisions of Machakos, Mwala, Nzaui and Kibwezi Districts (which were carved from the larger Machakos and Makueni districts) and they included Kalama, Kibwezi, Makindu, Matiliku, Mbitini, Mulala, Nguu and Yathui divisions. Farmers to be interviewed were selected randomly from their respective CIGs from membership lists, provided that the CIGs had requested for IC technical services, had registration certificates and were composed of at least 20-50 members. At least 10% of the farmers from each CIG were interviewed. The groups had significantly fewer male members (mean of 5) compared to a mean of 22 female members and seven out of the 29 CIGs were solely made up of female members. The oldest CIG was registered in 1996 with the latest registrations being those of 2008. A questionnaire was designed to gather periodic data on IC management as well as sales of IC, data necessary to monitor posttraining progress in IC management among this group of farmers. During the first week of December 2008, a total of 68 farmers were interviewed from where cross-sectional recall (3 month period in reference to September-November) data on IC sales and prices in addition to other IC management practices were gathered. The questionnaire requested farmers to recall how many birds they had sold, where this sale had occurred and prices received from the sales.

1.3 THEORETICAL AND EMPIRICAL FRAMEWORK

Some theoretical and empirical contributions explaining market behaviour include Barnum & Squire (1979), Singh, Squire & Strauss (1986), Sadoulet and de Janvry (1995). These assume properly functioning factor and product markets. In semi-subsistence situations much of which characterize small scale producers, production and consumption decisions are not separable and market participation takes place when a household’s shadow price is lower than the market price with an allowance for transaction costs. Similar approaches have focused on explaining such decision processes in technology adoption studies. In the market participation literature, the decision about market participation is a two-stage process, the first being the decision to participate while a related decision on how much market involvement comes next in that sequence. Some applications of these procedures in market participation analysis include Key, Sadoulet & de Janvry (2000), Bellemare & Barrett (2006). Studies have modelled this decision as being influenced by both on and off-farm level factors (Montshwe, Jooste & Alemu, 2004, Uchezuba, Moshabele & Digopo 2009). Recent studies have extended the approach to consider farmer preference for different aspects of the marketing systems themselves (Abdulai & Birachi, 2008, Blandon, Henson & Islam, 2009). In our study, it is hypothesised that since farmers make sale decisions sequentially (Bellemare & Barrett, 2006), then they first make the decision to sell (SELL=1) after which the decision on where to sell and how many birds to sell (SOLD) given prices at the chosen market is made. In this paper, we are concerned with the first decision, that of market participation. The underlying determinants (xi) of these separate decisions are assumed to be identical (Jha and Hojjati, 1994) and include the farmer’s initial endowment (flock size), distance to the chosen market (a dimension of transaction cost) and the price of a bird at the market. As members of CIGs, it is assumed that these farmers are not autarkic and further, that market participation involves sales of IC and not purchases. Observed sale prices are somewhere above the reservation price since with spot markets such as those characterizing IC, sellers do not have an exact map of prices offered but may only have a reservation price below which a sale agreement is not made. Other factors, such as the overall incentive environment, aggregate demand situation that are likely to shift the market response curve are assumed fixed in the short run, and their effects cannot be deciphered from this data set. In sum therefore, only prices and market distance are available for analysis in this dataset. To estimate the influence of these variables on the decision of farmers to sell IC, the model;

Prob (SELL=1) = 1 – F(-γX),……..(i)

for the probability of engaging in a sale (SELL=1) is estimated. Due to limitations in the dataset, in the absence of flock sizes [FZt-1] at period t-1 (i.e. when sale decision was made), we employ a rather contestable but simplifying assumption. A summation of reported sales (SOLD) and current flock size FZt1 will yield the situation at t-1 when the sale decision was made i.e. (FZt-1= SOLD + FZt). This result is what we use as the flock size in the regression. Further, prices (p) are assumed to be fixed in time i.e. pt-1 = pt . In many applications, it is assumed that F is either the cumulative normal (probit model) or the cumulative logistic distribution function (logit model) but in practice, there usually is no prior knowledge to justify this distributional assumption (Gerfin, 1996). The logistic regression approach is a powerful, convenient and flexible technique that can be used to describe the relationship of several independent variables to a dichotomous dependent variable (in this case SELL). Due to its mathematical convenience, the logistic regression has been used extensively (Greene, 2007). The probability of a result being in one of two responses is modeled as a function of the level of one or more explanatory variables. Thus, the probability of a farmer selling IC (probability SELL=1) is modeled as a function of prices and distance to the nearest market.

From equation ii above, the subscript j is the response category out of k categories (SELL=1 or SELL=0), i denotes individual farmers (1, 2, 3, 4…, n=68), ï¦ is the conditional probability, αo is the coefficient of the constant term, βj is the coefficient of the independent variable, Xij is a matrix of observed values and εi is a matrix of unobserved random effects.

Rearranging (ii) the logistic regression can be manipulated to calculate the conditional probabilities from (iii) above where e is the base of the natural logarithm (≈2.718).

1.4 DATA ANALYSIS

These estimations are implemented by invoking the proc logistic procedure in SAS. For most applications with discrete data, proc logistic is the preferred choice and it fits binary response or proportional odds models, provides a number of model-selection methods for identifying important prognostic variables from a large number of candidate variables, and computes regression diagnostic statistics (So, 1999). Unlike in classical regression analysis, the parameters from the logistic regression are not easy to interpret. Hence, to compute marginal effects, one can evaluate the expressions at the sample means of the data or evaluate the marginal effects at every observation and use the sample average of the individual marginal effects (Greene, 2007). For a continuous explanatory variable, x, e(βx) represents the change in odds for a unit increase in x (Schlotzhauer, 1993). The estimated empirical model is of the form SELL = f(FZ, Distance, Price) and is estimated by maximum likelihood. One of the farmers was found to be reporting information regarding exotic broilers and this observation was dropped from the analysis.

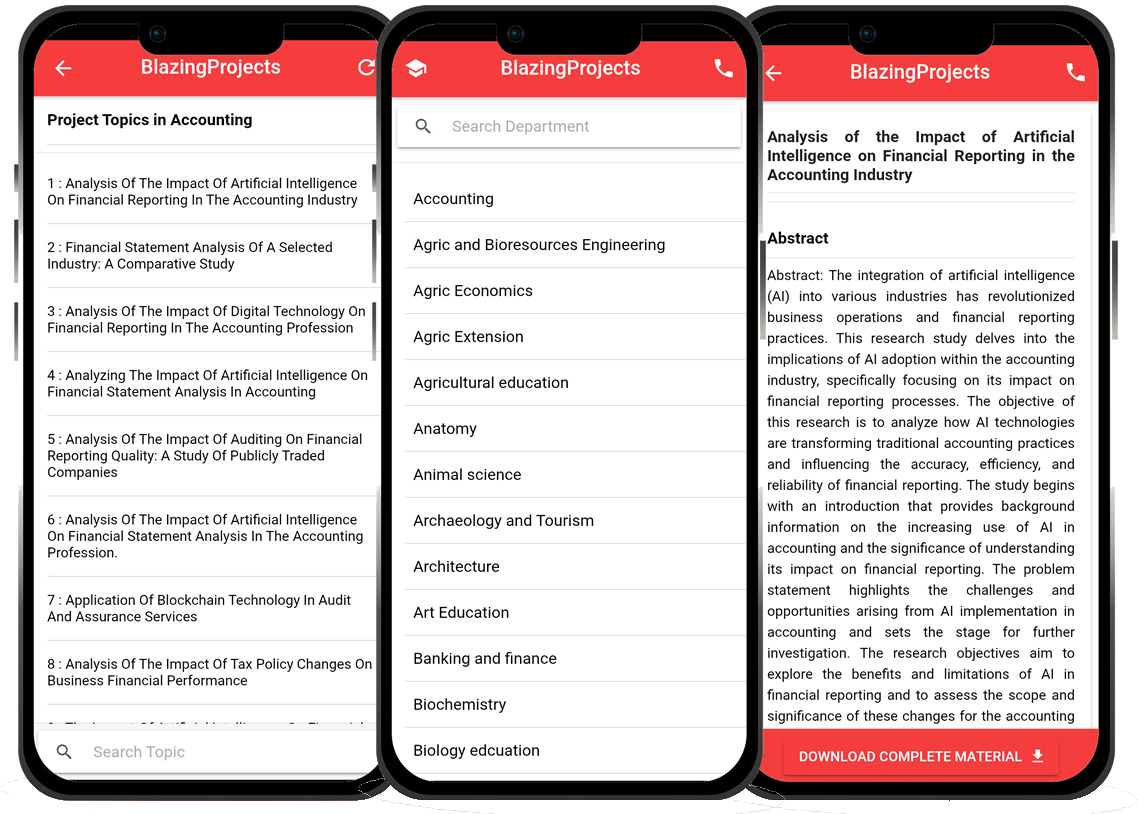

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Project Materials

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Software coding and Machine construction

🎓 Postgraduate/Undergraduate Research works

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Analysis of the impact of climate change on agricultural productivity and food secur...

The research project titled "Analysis of the impact of climate change on agricultural productivity and food security in a selected region" aims to inv...

Analyzing the Economic Impacts of Climate Change on Crop Production in Developing Co...

The research project titled "Analyzing the Economic Impacts of Climate Change on Crop Production in Developing Countries" aims to investigate the effe...

Analyzing the Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity and Food Securit...

The research project titled "Analyzing the Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity and Food Security in Developing Countries: A Case Study of...

The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallhold...

The project topic "The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallholder Farmers in a Developing Country" delves into...

Assessment of the Economic Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Production in a ...

The project titled "Assessment of the Economic Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Production in a Specific Region" aims to investigate the effec...

The impact of climate change on agricultural productivity: A case study of smallhold...

The impact of climate change on agricultural productivity is a critical issue affecting smallholder farmers in developing countries. Climate change poses signif...

The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallhold...

The research project titled "The Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallholder Farmers in a Developing Country" a...

Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selec...

The research project titled "Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selected Region" aims to investigate the r...

Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selec...

The research project titled "Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selected Region" aims to investigate the p...