Syntactic innovation processes in nigerian english

Table Of Contents

Thesis Abstract

This study investigates the syntactic features of Nigerian English which have been created

through the following processes – the use of subjectless sentences, reduplication, double subjects,

Pidgin-influenced structures, discourse particles, verbless sentences, and substitution. It observes

that the fact that some features of Nigerian English syntax are shared by other new Englishes is a

healthy development for the identity of non-native varieties around the world. It finally recommends

the codification of the new norms into variety-specific grammars and a common grammar

of new Englishes.

Thesis Overview

Introduction

The documentation of the various features of world Englishes has continued to

attract the attention of the linguistic scholar. Like other varieties of non-native

Englishes, West African English (WAE) has received considerable attention

(see, for example, Spencer 1971; Sey 1973; Bamgbose – Banjo – Thomas 1995;

Wolf 2001; Igboanusi 2002a). However, not much has been published on the

syntax of WAE in general and that of Nigerian English (NE) in particular. The

general belief is that grammatical features of national varieties of WAE are not

exclusive, and can also be found in other varieties of New Englishes (cf. Peter –

Wolf – Simo Bobda 2003: 44). For example, some scholars (notably Todd

1982; Bamgbose 1992; Bamiro 1995) observe that most of the syntactic patterns

in educated WAE are similar to those of other new Englishes. However, Todd

identifies the following syntactic variations of WAE: the indiscriminate use of

the tag questions isn’t it/not so? as in it doesn’t matter, not so/isn’t it?; differences

in the use of some phrasal verbs, e.g. cope up with for ‘cope with’; failure

to sometimes distinguish between countable and non-countable nouns (e.g. an

394 H. Igboanusi

advice, firewoods, behaviors). Bamiro’s (1995) study on the syntactic variation

of WAE was a more comprehensive investigation than earlier studies on the

subject matter. Using data from creative literature, Bamiro identifies the following

variations: subjectless sentences, e.g. Is because she’s a street walker for ‘It

is because…?’; deletion of -ly morpheme in manner adjuncts, e.g. Send patrol

van to pick her up quick (quickly); omission of function words, e.g. You say

truth (‘… the truth’); reduplication, e.g. Slowly, slowly the canoe moved like the

walk of an old man (gradually); formation of interrogatives without changing

the position of subject and auxiliary items, e.g. You’ve decided finally then?

(‘Have you finally decided then?’); tag questions, e.g. You are writing a paper

about our organization, not so? (‘Isn’t it?’); the use of the progressive aspect

with mental processes, e.g. Do you know what I am hearing? (‘Do you know

what I hear these days?’); non-distinctive use of reciprocal pronouns, e.g. The

captains (seven of them) looked at each other somewhat perplexed (‘one another’);

substitution of preposition in idiomatic usage, e.g. That is why they have

dragged the good name of my father, Joshua, son of Fagbola in the mud

(‘through’); focus constructions, e.g. You are a funny man, you this man.

With regard to NE, Banjo (1995: 217) observes that “empirical contrastive

study of the syntax of Nigerian and British English goes back to the era of error

analysis and contrastive linguistics” (e.g. the works of Tomori 1967; Banjo

1969; Odumuh 1981; Kujore 1985). Further works on the syntax of NE are

found in Odumuh (1987); Jowitt (1991); Bamgbose (1992); Kujore (1995) and

Banjo (1995). For example, Odumuh (1987: 60-65) identifies some “typical

variations between British English and Nigerian English as spoken by tertiary

educated informants”. Some of his examples include:

1) They enjoyed for BE ‘They enjoyed themselves’ (enjoyed occurs intransitively

in NE structure while it is usually transitive in BE);

2) He pregnanted her for BE ‘He made her pregnant’ (while NE structure uses

pregnanted as a verb, the word pregnant occurs in BE as an adjective);

3) You like that, isn’t it? for BE ‘You like that, don’t you?’ (in BE, while the

negative question tag is always determined by the verb, it is often represented

in NE by isn’t it?);

4) Give me meat for BE ‘Give me some meat’ (omission of article in NE

structure but not in BE structure);

5) I am having your book for BE ‘I have your book’ (NE structure uses the

ing as a stative marker);

6) He has been there since for BE ‘He has been there for some time’ (NE

structure uses an adverbial adjunct while BE structure has a preposition

followed by an adjunct).

Syntactic innovation processes … 395

Jowitt (1991) provides the following examples:

7) He offed the light for BE ‘He put off the light’ (1991: 112 – functional

derivation);

8) After the referee might have arrived the match will begin for BE ‘After the

referee has arrived the match will begin’ (1991: 120 – illustrates the use of

modals in NE);

9) My father he works under NEPA for ‘My father works in NEPA’ (1991:

121 – subject copying).

A further example is:

10) I have filled the application form for BE ‘I have filled in the application

form’ (Kujore 1995: 371 – illustrates the use of the verb fill in NE where

the preposition in is deleted);

It has to be pointed out here that some of the syntactic features illustrated as characterizing

WAE or NE by existing studies are in fact shared by other varieties of English.

For instance, Kachru (1982, 1983, etc.) has noted the following syntactic features

in South Asian English – reduplication, formation of interrogatives without

changing the position of subject and auxiliary items, tag questions, differences associated

with the use of articles, etc. Similarly, Skandera (2002: 98-99) identifies

some of the grammatical features of all ESL varieties which do not occur in Standard

English to include missing verb inflections, missing noun inflections, pluralisation

of uncountable nouns, use of adjectives as adverbs, avoidance of complex

tenses, different use of articles, flexible position of adverbs, lack of inversion in

indirect questions, lack of inversion and do-support in wh-questions, and invariant

question tags. The fact that many of the features of NE or WAE syntax identified in

earlier studies are also shared by other new Englishes is an indication that new Englishes

around the world now have identifiable linguistic characteristics. What needs

to be done is to intensify research on comparisons of these features across national

and regional varieties of non-native Englishes with a view to separating exclusive

features of these varieties from general or universal markers.

2. Syntactic innovation processes

The present study is an attempt to account for innovations in the syntax of NE

resulting from the sociolinguistic context of Nigeria, namely Nigerian Pidgin

English and the indigenous languages. How is “innovation” to be perceived? To

this question, Bamgbose (1998: 2) states that an innovation is to be seen as “an

acceptable variant”. The problem here is to determine whether a usage or struc396

H. Igboanusi

ture is an innovation or an error. What is seen as an innovation in a non-native

variety of English may be perceived as an error by most native speakers of English.

This problem is resolved the very moment we recognize the roles of social

convention as well as the relationship between social structure and linguistic form

in the use of new Englishes (cf. Banda 1996: 68). As Skandera (2002: 99) has

rightly observed, “if the characteristic features of an ESL variety come to be used

with a certain degree of consistency by educated speakers, and are no longer perceived

as ‘mistakes’ by the speech community, then that ESL variety becomes

endonormative (or endocentric), i.e. it sets its own norms”. Most of the examples

provided in the present investigation are so frequently heard in the speech of

many educated users of NE that they have ceased to be regarded as errors.

3. The data

The data for this study is based on my observations through recordings and field

investigations over the past five years. The recordings involve mainly the formal

and informal conversations of educated speakers of NE at different social

events, conferences and seminars, and students’ conversation as well as the

conversations of less educated NE speakers. The informal recordings reflect

different settings, sexes, ages, and ethnic and educational backgrounds. Some of

the data used in this work are also drawn from radio and television discussions.

I have adopted some of the categories of syntactic variation in WAE identified

by Bamiro, which are commonly found in NE. They include: reduplication,

subjectless sentences, substitution of preposition in idiomatic usage, and use of

double subjects. I have supplemented these categories with such new ones as

the use of verbless sentences, Pidgin-influenced structures, and structures influenced

by the use of discourse particles. Although many of the processes of syntactic

innovation discussed in this paper may occur in other varieties of WAE or

new Englishes, the sources of their influence and patterns of their use may be

different. It is also important to note that some of these syntactic categories are

very important features of creation in the style of many Nigerian and West African

writers (as Bamiro has shown) and are regularly founded in Nigerian newspapers

and magazines. In other words, they are not only restricted to colloquial

contexts. Their uses also cut across different levels of education.

I have carefully presented features which are found in both the basilectal and

acrolectal varieties of NE. I have identified the variety of NE in which a particular

feature is dominant. British English (BE) equivalents to the examples are

provided in parenthesis after each example.

English in Nigeria presents interesting problems because even the acrolectal

variety is caught between the Standard BE norms and basilectal pidgin. This

complex situation inevitably tolerates influences from Nigerian languages (as

Syntactic innovation processes … 397

with the case of discourse particles and reduplication) and Nigerian Pidgin (as

with the case of Pidgin-influenced structures).

3.1. Subjectless sentences

There is a preponderant use of subjectless sentences in the speech of NE users.

This practice involves the omission of the subject it in NE structures. Where

this omission occurs in the speech of educated users of NE, it is largely influenced

by the process of shortening in which the form It’s is reduced to Is, especially

in spoken English. Where it occurs in the speech of less educated users of

NE, it may be as a result of the influence of Nigerian Pidgin (NP) in which na is

transferred as is into NE structures. Consider the following examples:

a) Is very far (‘It’s very far’).

b) Is about three hours or more (‘It’s about three hours or more’).

c) Is about ten dollars (‘It’s about ten dollars’).

d) Is the woman (‘It’s the woman’).

Although subjectless sentences may not be found in the written form of the

acrolectal variety, it does exist in the written form of the basilectal variety.

3.2. Reduplication

Although reduplication has been treated by Bobda (1994) and Igboanusi (1998)

as lexical process of innovation, Kachru (1982) has noted that the reduplication

of items belongs to various word classes. For instance, some English words are

often reduplicated or repeated consecutively, either for emphasis, pluralisation,

or to create new meanings. Bobda (1994: 258) has rightly identified three categories

of words, which generally undergo the process of reduplication: numerals,

intensifiers and quantifiers. And as Igboanusi (2002b) has observed, while

the occurrence of a second numeral denotes ‘each’ (as in one-one, half-half), the

reduplication of an intensifier or a quantifier may be for emphasis (as in manymany,

now-now, before-before, fast-fast, fine-fine, slowly-slowly) or for pluralisation

(as in big-big, small-small). Examples are:

a) Please drive slowly-slowly because the road is bad (‘Please drive very

slowly because the road is bad’).

b) Before-before, food was very cheap in this country (‘In the past, food was

very cheap in this country’).

c) Please get me two more bottles of beer fast-fast (‘Please get two bottles of

beer for me very quickly’).

398 H. Igboanusi

d) I visited my friend’s campus and I saw many fine-fine girls (‘I visited my

friend’s campus and I saw several fine girls’).

e) Give me half-half bag of rice and beans (‘Give me half bag each of rice

and beans’).

f) We were asked to pay one-one hundred Naira as fine for contravening the

environmental sanitation law (‘We were asked to pay one hundred Naira

each as fine for contravening the environmental sanitation law’).

g) Do you have small-small beans? (‘Do you have small brand of beans?’).

h) You put it small small (‘It is put little by little’).

i) I have small small children in the house (‘I have young children in the

house’).

j) He claims not to have money and yet he’s busy building big-big houses all

over the city (‘He claims not to have money and yet he’s busy building

several big houses all over the city’).

k) Many many speak English (‘The majority of the people speak English’).

l) He visits me at three three weeks interval (‘He visits me at three week

intervals’).

m) Me I was running running (‘I was busy running’).

n) They went inside inside (‘They went to the interior part’).

o) Those are simple simple jobs to do (‘Those are very simple jobs to do’).

p) They live one one or two two (‘They live one or two to a room’).

Reduplication is mostly used in NE in colloquial contexts. And in the contexts

exemplified above, the reduplicatives small-small, fine-fine, one-one, fast-fast,

simple-simple, three-three and big-big are often heard in the speeches of educated

NE users. In general, reduplicatives are more commonly used by the less

educated speakers of NE than by educated speakers. The occurrence of reduplicatives

in NE stems from the influence of Nigerian languages and Pidgin.

3.3. Double subjects

The use of double subjects is another syntactic feature of NE. This process,

which is adopted to emphasize the subject, may involve the use of double pronouns

(e.g. this your/my, Me I) or the pronoun + a modifier/qualifier (e.g. we

children, we the poor).

a) Me I don’t have money (‘I don’t have money’).

b) Me I don’t know anything about the journey (‘I don’t know anything about

the journey’).

c) This your friend is not reliable (‘Your friend is not reliable’ OR ‘This

friend of yours is not reliable’).

Syntactic innovation processes … 399

d) This your regime is the worst we have witnessed in recent time (‘Your

regime is the worst we have witnessed in recent time’ OR ‘This regime of

yours is the worst we have witnessed in recent time’).

e) We children were sent to go and play (‘We were sent to go and play’ OR

‘Those of us who were young were sent out to go and play’).

f) We the poor are always cheated in this country (‘We are always cheated in

this country’ OR ‘Those of us who are poor are always cheated in this

country’).

The use of double subjects in constructions reflects the colloquial contexts of

some of Nigeria’s indigenous languages (e.g. Igbo and Yoruba) and Nigerian

Pidgin. Its colloquialism lies with the use of redundancy to achieve emphasis.

Note the use of double pronouns as subjects in examples (a) to (d) and the use

of pronoun + a modifier/qualifier in examples (e) and (f). The structures exemplified

in (3.3.) are found in the speech of both educated and less educated users.

Although the use of double subjects resembles the use of topicalisation,

which is commonly used in British English (e.g. John Coker, he’s to blame), the

two processes are different since the pronoun in topicalisation is in apposition to

the noun.

3.4. Pidgin-influenced structures

The strong influence of Pidgin English brings forth several NE structures. Let’s

examine the following samples:

a) We work farm (‘We are farmers’ or ‘We work on a farm’).

b) I have maize, yam, finish (‘I have maize and yam; that is it’).

c) I continue working at farm, finish (‘I continue to work at the farm; that is it’).

d) We sat down, finish (‘We sat down; that was it’).

e) We stayed together, ate, finish (‘We stayed together and ate; that was it’).

f) The Muslims are plenty than the Christians (‘The Muslims are more than

the Christians’).

g) I don’t know book (‘I’m not brilliant’).

h) If rice is done you keep it (‘Bring down the rice from fire when it is well

cooked’).

Note the deletion of preposition and determiner in (a), the emphatic use of finish

as a discourse marker in (b), (c), (d) and (e), the use of plenty as a comparative

item in (f), translation equivalent in (g), and (h).

400 H. Igboanusi

3.5. Structures with discourse particles

Several English structures exist in NE with discourse particles, which derive

either from the influence of NP or the indigenous language. Discourse particles

are frequently used in conversation. Consider the following examples:

a) You know Kemi now! (‘You should know Kemi’).

b) I live in Port Harcourt now! (‘You should know that I live in Port Harcourt’).

c) Wait now! (‘Please wait’).

d) Tomorrow is your birthday, abi? (‘Tomorrow is your birthday. Isn’t it?’).

e) Shebi it was you I gave some money yesterday (‘I think it was you I gave

some money yesterday’)

f) I won’t be there o (‘I will not be there’).

g) I’m tired of this life self (‘I’m even tired of this life’).

h) You’ll be here tomorrow, ko? (‘You’ll be here tomorrow, won’t you?’).

i) You disobeyed me and still went ahead to fight those people, ba? (‘You

disobeyed me and still went ahead to fight those people, didn’t you?’).

j) So, it is now confirmed that you were the one who initiated that move

against me; kai, I’m disappointed (‘So, it is now confirmed that you were

the one who initiated that move against me; I’m really disappointed’).

k) Haba! You should have told me before taking my money (‘What! You

should have told me before taking my money’).

l) Sha me, I have said what I wanted to say (‘As for me, I have said all I have

to say’).

m) I don’t know him sha (‘Anyway, I don’t know him’).

n) I have heard you, to! (‘OK, I have heard you’).

o) You’re the one that stole my money, to! (‘You’re the one that stole my

money, right!’).

p) I will deal with that man, wallahi (‘By God, I will deal with that man’).

q) Yauwa! I have seen what I’m looking for (‘I’m satisfied that I have seen

what I’m looking for’).

While 3.5 (a), (b), (c), (f) and (g) have pidgin as their source language, (d), (e),

(l) and (m) have Yoruba as their source language. The examples in (h), (i), (j),

(k), (n), (o), (p) and (q) are derived from Hausa and/or Fula. All the examples

are regularly found in NE-based conversations. In (a), (b) and (c), the discourse

particle now is used to emphasize the point that what is referred to is not unfamiliar

to the listener. In (d), the interjection abi is used as a discourse strategy to

confirm a piece of information. It may be equivalent to ‘Isn’t it?’ Like now, the

particle o in (f) is usually found in sentence-final position and gives emphasis to

Syntactic innovation processes … 401

the entire sentence. In addition, o signals the emotional involvement of the

speaker. Both ko in (h) and ba in (i) are interrogative markers. Kai and haba

express surprise. Shebi is a rhetorical question marker while yauwa expresses

feeling of satisfaction. Both sha and to are used to affirm a statement whereas

wallahi is equivalent to ‘honestly’ or ‘By God’. All the discourse particles discussed

above are only used colloquially. Discourse particles are veritable

sources of syntactic innovation processes in NE. The structures in (3.5.) can

occur in the conversations of both educated and less educated speakers of NE.

Although discourse particles are not originally English items, they are innovative

in creating NE structures.

3.6. Verbless sentences

Some verbless sentences exist in the discourse of NE speakers. In conversations

or exchange of pleasantries, one notices the frequent occurrence of the following

verbless sentences:

a) How? (‘How are you?’)

b) How now? (‘How are you?’)

c) How things? (‘How are things?’)

d) How work? (‘How is work?’)

e) How family? (‘How is your family?’)

f) How life? (‘How is life with you?’)

g) How body? (‘How is your body?’)

h) How market (‘How is business?’)

It may be argued that the deep structure of the verbless sentences in 3.6. may

not be really verbless but the result of a phonological rule in which single consonants

(in this case, [z]) are deleted between word boundaries. But at the surface

structure, they remain verbless. Although such verbless sentences are more

frequently found in the conversation of the less educated speakers of NE, they

also occur in the conversations of educated users of NE as a means of expressing

intimacy.

3.7. Substitution

Some instances of substitution, which involve the use of English idioms, have

been identified as processes of syntactic creation in NE. In all the examples

listed below, NE structures are used to replace BE idioms:

a) They are two sides of the coin (‘They are two sides of one coin’).

402 H. Igboanusi

b) He did the work on his own accord (‘He did the work of his own accord’).

c) I am not surprised that Chike and Andrew are such close friends; they are

birds of the same feather (‘I am not surprised that Chike and Andrew are

such close friends; they are birds of a feather’).

d) Dipo, I can’t believe that you’re now biting the finger that fed you (‘Dipo, I

can’t believe that you’re now biting the hand that fed you’).

e) The football match is going to be a child’s play (‘The football match is

going to be child’s play’).

f) I have been busy since morning cracking my brain over that question (‘I

have been busy since morning racking my brain over that question’).

g) You should not take the law into your hands (‘You should not take the law

into your own hands’).

h) By no stretch of imagination could anyone trust him (‘By no stretch of the

imagination could anyone trust him’).

i) And last but not the least is the perennial water problem in this state (‘And

last but not least is the perennial water problem in this state’).

j) He often shouts on top of his voice (‘He often shouts at the top of his

voice’).

As a syntactic process, the substitution of idiomatic usage involves three strategies

– omission, replacement and insertion. While examples (a), (g) and (h)

involve omission of some functional words, examples (e) and (i) concern the

insertion of articles. In the same vein, examples (b), (c), (d), (f) and (j) adopt the

process of replacement of some words.

4. Conclusion

What the data on syntactic innovation processes in NE shows is the evidence of

some aspects of the nativisation of English as a result of the contact of English

and indigenous languages and Pidgin. There is also evidence of some influence

of the pragmatic use of English in the Nigerian environment. It is true that some

features of NE syntax discussed in this paper are shared by other varieties of

WAE in particular and other varieties of English elsewhere. This trend suggests

a healthy development for the character of new Englishes worldwide. The

pedagogical implication of these processes relates to acceptability. Once the

“acceptability factor” (Bamgbose 1998: 4) is guaranteed, that is, when innovations

become accepted by speakers, the next process will be to codify the new

norms in the form of variety-specific grammars and the common grammar of

new Englishes. To further aid the codification of these various grammars, there

is a great need for comparative studies of the syntax of New Englishes.

Syntactic innovation processes … 403

REFERENCES

Allerton, D.J. – Paul Skandera – Cornelia Tschichold (eds.)

2002 Perspectives on English as a world language. Verlag. Basel: Schabe & Co. AG.

Bailey, Richard W. – Manfred Görlach (eds.)

1982 English as a world language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bamgbose, Ayo

1992 “Standard Nigerian English: Issues of identification”, in: Braj B. Kachru (ed.), 148-

161.

1998 “Torn between the norms: Innovations in World Englishes”, World Englishes 17/1: 1-17.

Bamgbose, Ayo – Ayo Banjo – Andrew Thomas (eds.)

1995 New Englishes: A West African perspective. Ibadan: Mosuro.

Bamiro, Edmund

1995 “Syntactic variation in West African English”, World Englishes 14/2: 189-204.

Banda, Felix

1996 “The scope and categorization of African English: Some sociolinguistic considerations”,

English World-Wide 17/1: 63-75.

Banjo, Ayo

1969 A contrastive study of aspects of the syntactic and lexical rules of English and

Yoruba. [Unpublished Ph.D dissertation, University of Ibadan.]

1995 “On codifying Nigerian English: Research so far”, in: Ayo Bamgbose – Ayo Banjo –

Andrew Thomas (eds.), 203-231.

Igboanusi, Herbert

1998 “Lexico-semantic innovation processes in Nigerian English”, Research in African

Languages and Linguistics 4/2: 87-102.

2002a A dictionary of Nigerian English usage. Ibadan: Enicrownfit.

2002b Igbo English in the Nigerian Novel. Ibadan: Enicrownfit.

Jowitt, David

1991 Nigerian English usage: An introduction. Ibadan: Longman.

Kachru, Braj B.

1982 “South Asian English”, in: Richard W. Bailey – Manfred Görlach (eds.), 353-383.

1983 The Indianization of English: The English language in India. New Delhi: Oxford

University Press.

Kachru, Braj B. (ed.)

1992 The other tongue: English across cultures. (2nd edition.) Urbana: University of Illinois

Press.

Kujore, Obafemi

1985 English usage: Some notable Nigerian variations. Ibadan: Evans.

1995 “Whose English?”, in: Ayo Bamgbose – Ayo Banjo – Andrew Thomas (eds.), 367-

380.

Odumuh, Adama E.

1981 Aspects of the semantics and syntax of “educated Nigerian English”. [Ph.D. dissertation,

Ahmadu Bello University.]

1987 Nigerian English. Zaria: Ahmadu Bello University Press Ltd.

Peter, Lothar – Hans-Georg Wolf – Augustin Simo Bobda

2003 “An account of distinctive phonetic and lexical features of Gambian English”, English

World-Wide 24/1: 43-61.

404 H. Igboanusi

Sey, K.

1973 Ghanaian English: An explanatory survey. London: Macmillan.

Simo Bobda, Augustin

1994 “Lexical innovation processes in Cameroon English”, World Englishes 13/2: 245-

260.

Skandera, Paul

2002 “A categorization of African Englishes”, in: D. J. Allerton – Paul Skandera – Cornelia

Tschichold (eds.), 93-103.

Spencer, John (ed.)

1971 The English language in West Africa. London: Longman.

Todd, Loreto

1982 “The English language in West Africa”, in: Richard W. Bailey – Manfred Görlach

(eds.), 281-305.

Tomori, S. H. O.

1967 A study in the syntactic structures of the written English of British and Nigerian

grammar school pupils. [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Ibadan.]

Wolf, Hans-Georg

2001 English in Cameroon. (Contributions to the Sociology of Language 85.) Berlin: Mouton

de Gruyter.

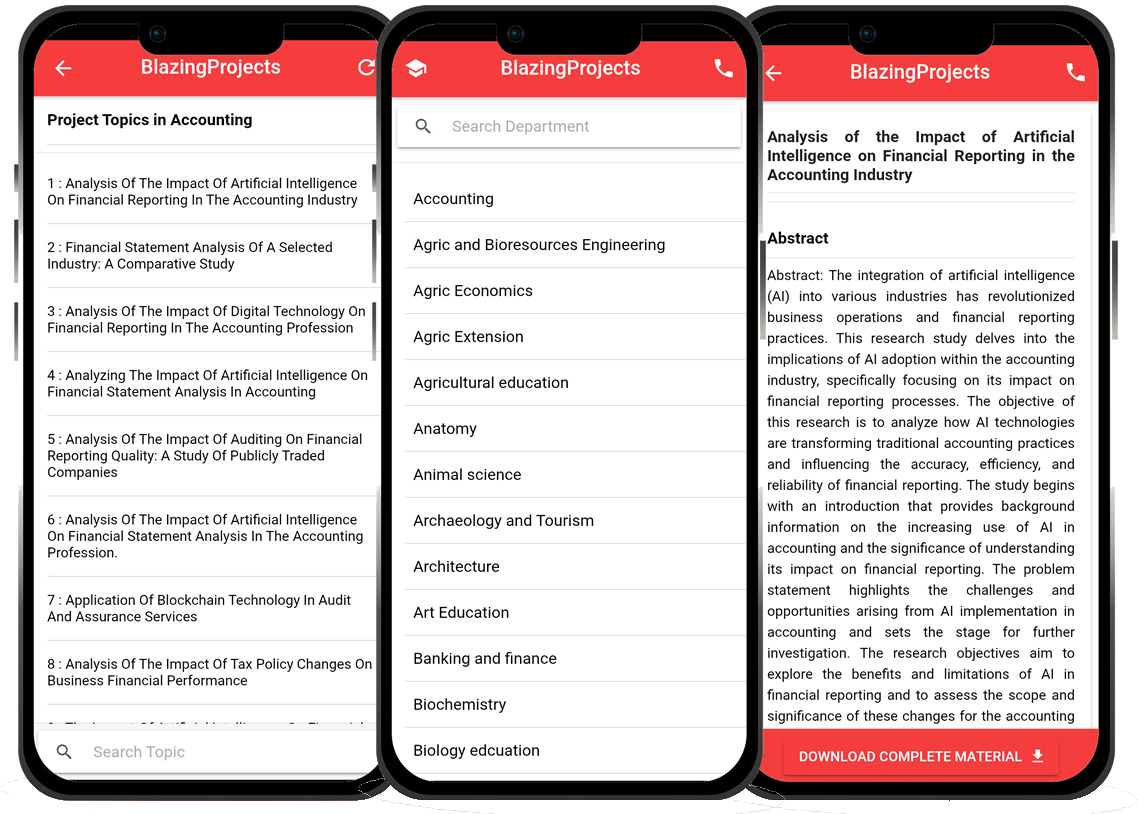

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Research Thesis

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Thesis-to-Journal Publication

🎓 Undergraduate/Postgraduate Thesis

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Implementing a Social Enterprise Model for Sustainable Impact: A Case Study Analysis...

The project titled "Implementing a Social Enterprise Model for Sustainable Impact: A Case Study Analysis" aims to explore the practical implementation...

Developing a Sustainable Business Model for Online Food Delivery Services...

The research project, "Developing a Sustainable Business Model for Online Food Delivery Services," aims to address the growing importance of sustainab...

Strategies for Scaling a Sustainable Social Enterprise in Developing Countries...

The project titled "Strategies for Scaling a Sustainable Social Enterprise in Developing Countries" aims to explore and analyze the various strategies...

Developing a Digital Platform to Connect Local Artisans with Global Markets: A Case ...

The project titled "Developing a Digital Platform to Connect Local Artisans with Global Markets: A Case Study in Sustainable Entrepreneurship" aims to...

Developing a Business Model for Sustainable Fashion Startups...

The project titled "Developing a Business Model for Sustainable Fashion Startups" aims to address the need for innovative and sustainable business mod...

Developing a Sustainable Business Model for Food Delivery Services in Urban Areas...

Overview: The project titled "Developing a Sustainable Business Model for Food Delivery Services in Urban Areas" aims to address the growing demand f...

Utilizing Blockchain Technology for Supply Chain Transparency in Small Businesses...

The project titled "Utilizing Blockchain Technology for Supply Chain Transparency in Small Businesses" aims to explore the potential benefits and chal...

Implementing a Sustainable Business Model for a Social Enterprise in a Developing Co...

The project titled "Implementing a Sustainable Business Model for a Social Enterprise in a Developing Country" aims to address the critical need for s...

The Impact of Social Media Marketing on Small Business Growth: A Case Study of Local...

The research project titled "The Impact of Social Media Marketing on Small Business Growth: A Case Study of Local Retail Stores" aims to examine the i...