The linguistic features of nigerian english and their implications for 21st century english pedagogy

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction 1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Nigerian English 2.2 Evolution of Nigerian English

2.3 Linguistic Features of Nigerian English

2.4 Variations in Nigerian English

2.5 Influence of Indigenous Languages on Nigerian English

2.6 Impact of Globalization on Nigerian English

2.7 Nigerian English in Literature

2.8 Nigerian English in Education

2.9 Nigerian English in Media

2.10 Comparative Analysis with Other Varieties of English

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Methodology Overview 3.2 Research Design

3.3 Data Collection Methods

3.4 Sampling Techniques

3.5 Data Analysis Procedures

3.6 Ethical Considerations

3.7 Validity and Reliability

3.8 Limitations of Research Methodology

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Presentation of Findings 4.2 Analysis of Linguistic Features

4.3 Interpretation of Data

4.4 Discussion on Implications for English Pedagogy

4.5 Comparison with Existing Literature

4.6 Addressing Research Objectives

4.7 Recommendations for Further Research

4.8 Practical Applications and Future Directions

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Conclusion 5.2 Summary of Findings

5.3 Contribution to Knowledge

5.4 Implications for English Language Teaching

5.5 Reflections on the Research Process

Thesis Abstract

Like its users, one important feature of language is its dynamism. Thus, language

adapts to situational constraints as its users vary across regional/geographical, social,

educational, occupational, etc. domains. English is such a typical language that, as a

result of vast geographical distribution, has often assumed the peculiarities of different

societies that use it informing the notion of variety. Varieties of English thus exist among

the three Kachruan circles among which Nigerian English (NE) is situated. This paper,

building on the works of several scholars who have approached the NE phenomenon

from different perspectives, discusses the phonological, morpho-syntactic, lexicosemantic

and pragmatic features NE. It is submitted that the issue of variation and/or

deviation characterizing the NE be harmonized within the Global English (GE) variety

and Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) be fully incorporated and

implemented so that the current state of English language teaching and learning in

Nigeria would transcend the “state of confusion” (Babatunde, 2002) it is now. This is

considered expedient so that the Nigerian users of English would be able to cope

meaningfully with the challenges posed by the knowledge-driven twenty-first century, in

which English is assuming greater roles and significance.

Thesis Overview

1.0. Introduction

One sociolinguistic implication of the diffusion of English language – an amalgam

of the three paltry languages of the Jutes, Angles and the Saxon, unknown in the 6th

Century AD – in the global scene is the emergence of World Englishes (WE) (Adegbija,

1994). English is now spoken all over the world among various categories of speakers.

The Kachruan ‘three concentric circles’ of English users are the Inner Circle, the Outer

Circle and the Expanding Circle (Kachru,1985).These are normatively characterized as

Norm-producing, Norm-developing and Norm-dependent users. This sociolinguistic

scenario is also aptly captured by Quirk (1985:1-2) as English as a Native language(ENL)

countries (Great Britain, United States, Canada, Australia, South-Africa), English as a

Second Language countries (e.g. Nigeria, India, Singapore, Tanzania, Zambia, Ghana,

2

Uganda, Kenya, etc.) and English as a Foreign Language countries (e.g. Germany,

Russia, China, France, Belgium, Italy, Saudi Arabia, Greece, etc.) (Adedimeji, 2006).

The international explosion of English has made it cease to be an exclusive

preserve of the English people (Adegbija,1994:209).As there are more speakers of

English in the outer and expanding circles than the norm-producing inner circle, English

is now seen as a global language, susceptible to the subtleties and idiosyncracies of

regional and cultural linguistic behaviours. Indeed, Bailey and Gorlach (1982) provide a

panoramic overview of world varieties of English as clothed by their various distinctive

peculiarities and identifiable local flavour. Some of the issues that have arisen from this

phenomenon as rightly identified by Adegbija (1994) are: (a) the growth and

development of indigenized, nativized indiosyncratic varieties, (b) the issue of

intelligibility or otherwise of the emerging varieties and the implications of this for an

international or global variety, (c) the acceptability of the different varieties and (d) the

determination of which variety should be the ideal norm to use as a model, especially in

education.

As “sociolinguistics tries to cope with the messiness of language as a social

phenomenon” (Coulmas, 2003:263), such messiness may be said to abound in the sociogeographical

spread of English across the world. Some world varieties of English, aspects

of Nigerian English inclusive, would still need to be interpreted to other speakers of

English before they are intelligible. This is a result of the overbearing local idioms and

linguistic patterns that characterize such varieties or uses. Trask (1995:75) provides such

structures of English varieties that are quite normal to their users as follows:

1. We had us a real nice house

2. She’s a dinky-di Pommie Sheila.

3. I might could do it.

4. The lass didn’t gan to the pictures, pet.

5. They’re a lousy team any more.

6. I am not knowing where to find a stepney.

The expressions above are marked by dialects or regional forms. Almost all of them

may have to be interpreted to Nigerian and other English speakers apart from their

specific users. As adapted from Trask (1995:74-75), the first expression is peculiar to the

3

south of the USA, with the extra “us” and the form is sometimes used elsewhere. The

second structure is Australian English, a native speaker variety, and it means “she’s a

typical Englishwoman.” The third example is a normal expression in parts of the

Appalachian Mountain region of the USA as well as many parts of Scotland; it means “I

might be able to do it.” The fourth structure is ‘Geordie’, the speech of the Tyneside area

of northeastern England and it means “The girl didn’t go to the cinema.” The fifth

expression is typical of a large part of northeastern USA and the use is considered

mysterious because it means “They used to be a good team but now they are lousy” the

opposite of they are not a lousy team anymore .The last (number 6) example is an Indian

English expression and it means “I don’t know where to find a spare wheel.”

What the above shows that English adapts to the socio-cultural constraints that

characterize various contexts of its use. A world language par excellence, its propensity

to adapt to the dictates of its users, whoever they are, appears to be inimitable. This paper

overviews the linguistic features that typify Nigerian English and highlights the

implications of such in an unfolding century that poses greater challenges for mankind,

economically, politically, culturally, educationally among others, and in which

internationalism and globalization will become more pervasive. The present exercise is

relevant because most previous attempts at addressing features of the Nigerian English

have been particularistic and unidirectional, focusing on individual or two levels of

linguistic description. For instance, all of Banjo (1971), Adetugbo (1977), Bamgbose

(1982), Jibril (1979;1982), Eka (1985) among others have focused on phonology.

Odumu (1981) focuses mainly on syntax and semantics and Banjo(1969), Adesanoye

(1973), Kujore (1985), Awonusi (1990)and Jowitt (1991) treat aspects of morphology

and syntax extensively in their treatises. Akere (1982), Adegbija (1989), Bamiro (1991),

Alabi (2000) among others have been preoccupied with lexico-semantic features while

fragments of pragmatic features of Nigerian English can be gleaned from the works of

Akere (1978), Adetugbo (1986), Bamgbose (1995) and Banjo(1996).The representative

features in all the above are adopted while others are added as found desirable.

4

2.0. The Linguistic Features of Nigerian English

The English language in Nigeria exhibits certain distinctive features that cannot be

ignored. This situation results from the range of social, ethnic and linguistic constraints

posed by the second language context in which the language operates. The term,

“Nigerian English”, can be broadly defined as “the variety of English spoken and used by

Nigerians” (Adeniyi, 2006: 25). Nigerian English has generated as a lot of scholarly

interest since as far back as 1958 when L.F. Brosnahan published his article “English in

Southern Nigeria.” The question of what Nigerian English is and what it is not has

pitched scholars into two camps: the deviation school and the variation school. The

deviation school maintains that Nigerian English does not exist and what is referred to by

the term is just a concatenation of errors underpinning the superficial mastery of the

Standard British English (SBE) by Nigerians. Scholars in this school include Vincent,

Salami, Prator, Brann, etc. To the members of this school, Nigerian English is anomalous

and the banner of the SBE is upheld as the existing form, “even though their own speech

and usage provide ample evidence if its (Nigerian English) existence” (Bamgbose,

1982:99). The variation school represents the contemporary viewpoint and a vast army of

scholars like Banjo, Bamgbose, Awonusi, Odumu, Adetugbo, Adegbija, among several

others, belong here. The school affirms the existence of a distinct variety or dialect in

Nigeria, with its own subtypes along basilectal (non-standard), mesolectal (general,

almost standard) and acrolectal (standard Nigerian English) lines (Awonusi, 1987, cf.

Babatunde, 2001).

The question of which school is right or wrong as determined may be outside the

scope of the present work though appropriate entailments to that effect are made. What is

incontrovertible is that the use of English in Nigeria is characterized by the idiosyncratic

norms reminiscent of the Nigerian linguistic ecology. The features reflect the submission

of Soyinka (1988:126) regarding the use of English by Nigerian and other non-native

speakers:

And when we borrow an alien language to sculpt or paint in, we

must begin by co-opting the entire properties in our matrix of

thought and expression. We must stress such a language, stretch

it, impact and compact it, fragment and reassemble it with no

apology, as required to bear the burden of experiencing and of

5

experiences, be such experiences formulated or not in the

conceptual idioms of the language.

2.1. Phonological Features of Nigerian English

1. Each syllable of a given speech is of nearly the same length and given the same stress.

The final syllable is often stressed, even if it is not a personal pronoun. There is no

differentiation between strong and weak stresses (Alabi, 2003;Ufomata,1996).

2 Stress misplacement: The stress pattern of English words in NE is different. This

discrepancy is illustrated by Jowitt (1991:90-92) in lexical, phrasal and clausal structures

as follows:

SBE PNE

FIREwood fireWOOD

MAdam maDAM

PERfume perFUME

PLANtain planTAIN

SAlad saLAD

TRIbune triBUNE

conGRAtulate congratuLATE

inVEStigate investiGATE

SITting-room SITting-room or sitting ROOM

DeVElopment fund Development FUND

It SHOULD be It should BE

3. Interference: This is the negative transfer of what obtains in the source language

or Nigerian languages to the target language or English. Phonological interference

is of five types: a) Over-differentiation of sounds,b) under-differentiation of

sounds, c) re-interpretation of sounds, d.) actual sound substitution and e)

hypercorrection (Ofuya,1996:151).

a.) Overdifferentiation arises when distinctions made in Nigerian languages that are

not realized in English are forced on the English language. Examples are:

6

/kwÉ’rent/ for current in Hausa.

b.) Under-differentiation occurs when more than a sound in mother tongue is used for

more than one sound in English. Generally, Nigerians tend to substitute long vowel

sounds with the short sounds, the latter of which is only applicable in their mother

tongues. Hence,

/i:/ is realized as /i/

/a:/ :: :: :: /a/

/u:/ :: :: :: /u/

/ε:/ :: :: / ε /

c.) Reinterpretation happens when a sound in English is realized as its close

counterpart in English. Hence,

/ Ê/ is interpreted/ realized as / É /

/ É/ :: :: :: / É /

/ æ/ :: :: :: / É /

/ f / :: :: :: / p / especially in Hausa Nigerian English.

d.) Actual sound substitution is occasioned by the substitution or replacement of

sounds absent in Nigerian languages. Hence,

/ ï½ / is substituted with / t /

/ ð / :: :: :: / d /

/ ʧ / :: :: :: / ∫ / or / s/

/ v / :: :: :: / f /

/ z/ :: :: :: / s /

/ Ê / :: ::: :: / ∫ /

/

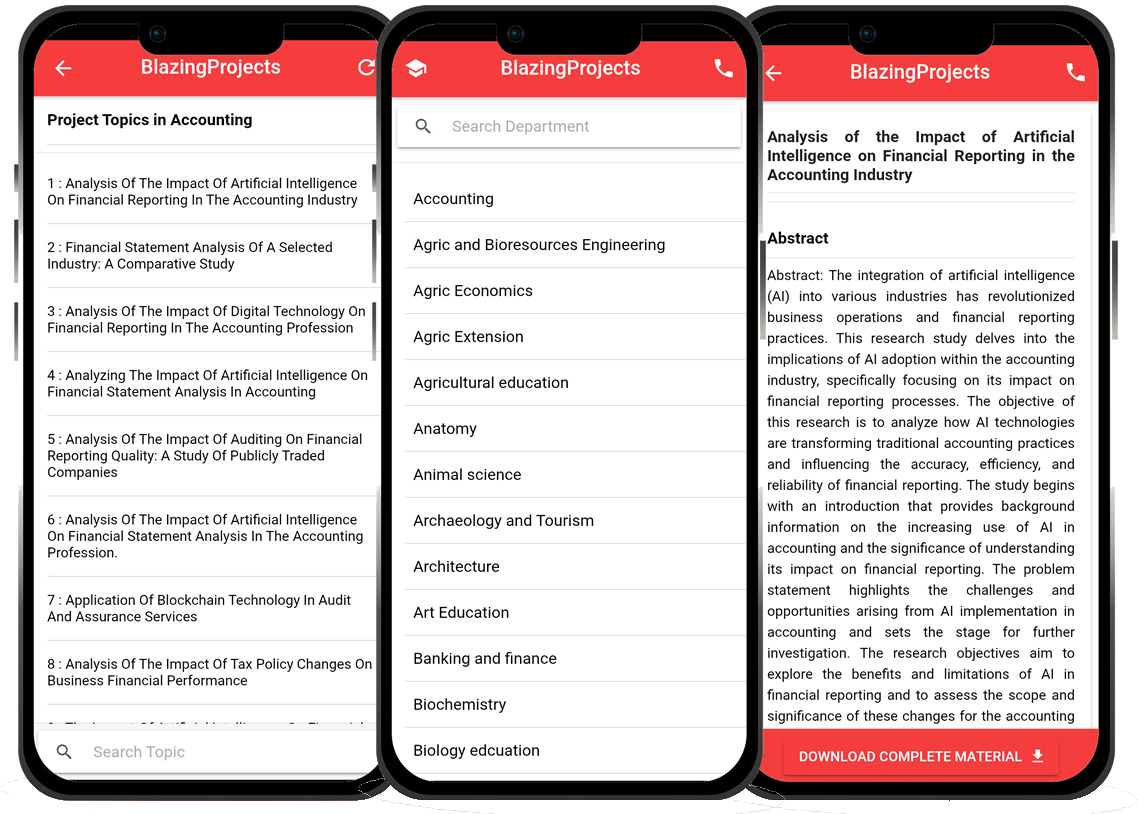

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Research Thesis

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Thesis-to-Journal Publication

🎓 Undergraduate/Postgraduate Thesis

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

An Analysis of Gender Roles in Contemporary Young Adult Literature....

The research project titled "An Analysis of Gender Roles in Contemporary Young Adult Literature" aims to delve into the portrayal and representation o...

The Role of Women in Post-Colonial African Literature: A Comparative Analysis...

The research project titled "The Role of Women in Post-Colonial African Literature: A Comparative Analysis" aims to explore and analyze the portrayal ...

An Exploration of Gender Representation in Contemporary Nigerian Literature...

The research project titled "An Exploration of Gender Representation in Contemporary Nigerian Literature" seeks to delve into the intricate ways in wh...

The Representation of Identity in Postcolonial Literature...

The research project titled "The Representation of Identity in Postcolonial Literature" aims to explore and analyze the various ways in which identity...

Exploring the Portrayal of Gender Roles in Contemporary African Literature...

The project titled "Exploring the Portrayal of Gender Roles in Contemporary African Literature" aims to delve into the representation and depiction of...

The Representation of Gender in Contemporary African Literature...

The project titled "The Representation of Gender in Contemporary African Literature" aims to explore and analyze the portrayal of gender in literary w...

Exploring the Use of Magical Realism in Contemporary African Literature...

The project, titled "Exploring the Use of Magical Realism in Contemporary African Literature," delves into the intricate relationship between magical ...

Exploring the Use of Magical Realism in Contemporary English Literature...

The project titled "Exploring the Use of Magical Realism in Contemporary English Literature" aims to delve into the widespread practice of employing m...

Exploring the Portrayal of Mental Health in Contemporary Literature: A Comparative A...

The research project, "Exploring the Portrayal of Mental Health in Contemporary Literature: A Comparative Analysis," delves into the depiction of ment...