A STUDY OF RISK MANAGEMENT PRACTICES IN THE NIGERIAN CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Evolution of Risk Management2.2 Theoretical Framework of Risk Management

2.3 Risk Management Practices in Construction Industry

2.4 Challenges in Implementing Risk Management

2.5 Benefits of Effective Risk Management

2.6 Case Studies on Risk Management in Construction Projects

2.7 International Best Practices in Risk Management

2.8 Technology and Innovation in Risk Management

2.9 Risk Management Standards and Guidelines

2.10 Future Trends in Risk Management

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Design3.2 Data Collection Methods

3.3 Sampling Techniques

3.4 Data Analysis Procedures

3.5 Research Ethics

3.6 Research Limitations

3.7 Research Validity and Reliability

3.8 Research Constraints

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Overview of Research Findings4.2 Analysis of Risk Management Practices in Nigerian Construction Industry

4.3 Comparison with International Standards

4.4 Identification of Key Challenges

4.5 Recommendations for Improvement

4.6 Case Studies Illustrating Effective Risk Management

4.7 Stakeholder Perspectives on Risk Management

4.8 Implications for Future Research

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Findings5.2 Conclusions

5.3 Contributions to Knowledge

5.4 Practical Implications

5.5 Recommendations for Future Research

Thesis Abstract

ABSTRACT

The multiplier effect of the construction industry to both developed and developing countries cannot be overemphasised. The 2012 construction sector review purports that the UK construction industry has an annual turnover of more than £100 billion and accounts for 10 per cent of the country’s GDP. In contrast Nigeria, which is urbanising at one of the fastest rates in the world, contributes only 3.2 per cent in terms of Gross Domestic Product. In other words, the contributions of the construction industry warrants persistent review of its gaps; risk and uncertainty are particularly rife in most Nigerian construction projects, and the cost implications are severe enough to influence its low GDP contribution and beyond. The aim of this research effort is to understand the competitive advantage (value chain) of enshrining risk management practices up and down the construction supply chain. A literature review was first conducted to identify and categorise different risk management practices on and off a construction site. In turn, the population for the study was determined using stratified random method of sampling. The units of analysis in this case study are contractual interfaces and organisational structure, of which there can be hundreds in a typical case. After an initial scoping study – the administering of 150 questionnaires – of risk management practices amongst general contractors. Fourteen in-depth interviews were conducted across a typical value chain. Drawing on principles of grounded theory, interview transcripts were analysed through a combination of content analysis and graphical representation of contractual and organisational structures. Clients and contractors were found to be risk averse even though they claimed to have formal written procedures for risk management. Their awareness of the importance of risk management in construction business is more of lip services. A graphical representation of the Nigerian contractual structure, supply chain and value chain was achieved. Consequently, a conceptual model is developed for enshrining risk management practices in developing countries. The micro and macro implication of the prescribed model is subject to its testing and validation.

Thesis Overview

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND STUDY

Nigеriа is undoubtedly one of the mоѕt influеntiаl аnd mоѕt Ñ•trаtеgic countries in Africa tоdаy in viеw оf itÑ• pоpulаtiоn, itÑ• vаѕt hydrоcаrbоn rеѕоurcеѕ аnd thе cоmmitmеnt оf thе gоvеrnmеnt tо dеmоcrаcy, аnti-cоrruptiоn аnd Ðfricаn Unity. Thе еcоnоmy which hеаvily dеpеnds оn itÑ• оil ѕеctоr (which also depends on its construction sector) аccоuntÑ• fоr ѕоmе 90 pеrcеnt оf еxpоrt rеvеnuеѕ аnd 41 pеrcеnt оf itÑ• Grоѕѕ Dоmеѕtic Prоduct (Wоrld Bаnk, 2006). Dеѕpitе itÑ• rеlаtivе аbundаncе оf minеrаl rеѕоurcеѕ, thе еxpаnÑ•iоn оf Nigеriа’Ñ• оil ѕеctоr hаѕ bееn stifled by itÑ• аntiquаtеd infrаѕtructurе аnd thе fruÑ•trаting Ñ•lоw mоvеmеnt оf gооdÑ• thrоugh Nigеriа’Ñ• mаjоr pоrtÑ•. It iÑ• оn rеcоrd thаt thе rаpid еcоnоmic dеvеlоpmеnt in Nigеriа hаѕ bееn lаrgеly due tо thе dеlibеrаtе pоlicy оf thе gоvеrnmеnt оn tеchnоlоgicаl and infrastructural cаpаcity building thrоugh invеѕtmеnt оppоrtunitiеѕ thаt еxiÑ•t in thе оil аnd gаѕ induÑ•try, in humаn cаpitаl аnd inÑ•titutiоnаl building. Lооking bаck оn thе advent оf thе оil phеnоmеnоn, thе Nigеriаn еcоnоmy thоugh аgrо-bаѕеd wаѕ rеlаtivеly divеrÑ•ifiеd. Thеrе еxiÑ•tеd ѕеlf-Ñ•ufficiеncy in fооd prоductiоn, with еnоugh tо fееd thе pоpulаtiоn аnd еxtrа fоr еxpоrt. Thе cоuntry hаd а Ñ•trоng еxpоrt ѕеctоr аnd budding induÑ•triаl bаѕе. Thеrе wеrе functiоning lаwÑ•, inÑ•titutiоnÑ•, ѕоciаl аnd еcоnоmic infrаѕtructurе аѕ wеll аѕ limitlеѕѕ jоb оppоrtunitiеѕ. Ðbоvе аll, ѕеcurity оf lifе аnd prоpеrty wаѕ аdеquаtе аnd fоrеign invеѕtоrÑ• hаd cоnfidеncе in thе еcоnоmy. ThiÑ• wаѕ thе Ñ•ituаtiоn оn grоund bеfоrе Nigеriа’Ñ• firÑ•t еxpоrt оf crudе оil in Fеbruаry 1958.

Ð…incе the 1970Ñ•, like the thе оil аnd gаѕ induÑ•try, the construction industry, which draws on its multiplier effect hаѕ bеcоmе fundаmеntаl for wealth distribution in thе Nigеriаn еcоnоmy. The Nigerian construction industry plays a major role in ensuring the oil and gas industry contributes sufficient rеvеnuе аѕ wеll аѕ thе fоrеign еxchаngе еаrningÑ• fоr thе cоuntry. Thе diÑ•cоvеry оf оil аnd gаѕ оpеnеd up thе induÑ•try, allowing fоrеign multinational pаrticipаtiоnÑ• likе thе Mоbil, Ðgip аnd Tеxаcо/Chеvrоn rеѕpеctivеly tо jоin thе еxplоrаtiоn еffоrtÑ• bоth in thе оnÑ•hоrе аnd оffÑ•hоrе аrеаѕ оf Nigеriа. ThiÑ• dеvеlоpmеnt wаѕ еnhаncеd by thе еxtеnÑ•iоn оf thе cоncеѕѕiоnаry rightÑ• prеviоuÑ•ly а mоnоpоly оf Ð…hеll BP. Thе government аims to ensure that construction helps tо аccеlеrаtе thе pаcе оf еxplоrаtiоn аnd prоductiоn оf pеtrоlеum. Tоdаy, thе оil аnd gаѕ induÑ•try in Nigеriа hаѕ riѕеn vеry fаѕt аnd Ñ•tеаdy tо hоѕt thе wоrld’Ñ• 10th lаrgеѕt rеѕеrvеѕ аt аbоut 25 billiоn bаrrеlÑ•. Within thе Оrgаniѕаtiоn оf Pеtrоlеum Еxpоrting Cоuntriеѕ (ОPЕC), Nigеriа iÑ• in thе 6th pоѕitiоn in tеrmÑ• оf rеѕеrvеѕ аnd dаily prоductiоn. Nigеriа’s dаily аvеrаgе prоductiоn iÑ• оvеr twо milliоn bаrrеlÑ• аnd hаѕ thе cаpаcity tо еxcееd hеr rеѕеrvеѕ tо 30 billiоn bаrrеlÑ•. Thе аѕpirаtiоn оf gоvеrnmеnt iÑ• tо accommodate OPEC’s oil supply and demand outlook to 2035 (WOO 2013), with а prоductiоn оf аbоut 4m b/d by thе tаrgеt dаtе. ÐÑ• pаrt оf thе аѕpirаtiоn, thе gоvеrnmеnt thrоugh Public Private Partnership initiatives is hoping that the needed building and infrastructural services would be in place. Hence the role of Nigeria's construction industry cannot be overemphasized.

1.2 RESEARCH CONTEXT

the construction industry The construction industry has a very strong multiplier effect in developed and developing economies. The UK construction industry has an annual turnover of more than £100 billion and accounts for almost 10% of the country’s GDP (Office of National Statistics, 2013). On the other hand, the Nigerian construction sector, which occupies an important position in the nation’s economy accounts for 1.4% of its GDP (Aibinu and Jagboro 2002, Dantata 2007, BanaitienÄ— et al 2011, Ogbu 2013). In other words, the contribution of the construction industry warrants persistent review of its gaps. Risk and uncertainty are rife in every undertaken construction project, and the cost implications are severe enough to justify its very low GDP contribution. More so, when uncertainty is linked with infrastructure projects that are stalled due to budget overruns and conflict.

Unlike the developed countries, genuine risk management practices are still at infancy stage in Nigeria (Odunsami et al 2002). Clients and contractors’ knowledge of its significance is skewed and it is no news that they are risk shy (Winch 2002). Risk exists when a decision is expressed in terms of a range of possible outcomes and when known probabilities can be attached to the outcome. Similarly, uncertainty exists when there is more than one possible outcome of a course of action but probability of each outcome is not known (Smith et al 2006). Thus the application of risk management allows for effective management of expected events where the outcome is either to the benefit or detriment of the decision maker where the ultimate purpose of risk management is risk mitigation (Shofoluwe and Bogale 2004). The paucity of theoretically hinged risk management research on evaluating and assessing risk management practices and techniques in peculiar environments like Nigeria is the motivation for undertaking this study. In line with existing frameworks for identifying, monitoring, responding and classifying risk (Flanagan and Norman 1993; Chapman 2001, and Perry and Hayes 1985); this research effort will address the risk management culture of clients, main contractors and sub contractors in Nigeria.

Flanagan and Norman (1993) used general systems of work breakdown structure as a framework to prescribing three ways of classifying risk (identifying the consequences, type and impact of risk). Similarly, Chapman (2001) grouped risks into four subsets of environment, industry, client and project. Also, Shen et al (2001) classified risk as financial, legal, management, market, policy, technical and political. Zou et al (2007) risk classification is project based and Perry and Hayes (1985) presents a list of factors extracted from several sources which were divided in terms of risk retainable by contractors, consultants and clients. There is no doubt that lessons from risk management studies in the developed world can contribute to risk management practices in Nigeria. But the peculiar economic environment, culture and political make-up of the Nigerian construction sector affirms the need to understand risk management with emphasis on Nigerian construction projects.

Notably, projects are products of change implementation. However, every project is unique; The construction industry, perhaps more than other sectors, is overwhelmed with risks (Sanvido et al 1992). Ehsan et al. (2010) argued that the industry is highly risk prone, with complex and dynamic project environments creating an atmosphere of high uncertainty and risk. The industry is vulnerable to various technical, socio-political and business risks. Deviprasad (2007) further stated that too often this risk is not dealt with satisfactorily and the industry has suffered poor performance as a result. According to Pritchard (2001), most of the decisions of construction projects, including the simplest ones, involve risks. The procedure of taking a project from inception to completion, and then its usage is complex as it involves time-consuming design and production processes (Ahmed & Azhar, 2004). The main role of project management activities is to drive construction operations in order to reach or even go beyond the objectives of the client and other stakeholders (Monetti et al., 2006). Risk management is fundamental to accomplish those objectives, by not only trying to keep away from challenges caused by some special events or uncertain conditions, but also acting as a guide in order to maximise the positive results.

Risk Management refers to the culture, processes, and structures that are directed toward effective management of risks including potential opportunities and threats to construction project objectives (Shofoluwe and Bogale 2004). Although it is widely studied, risk still lacks a clear and shared concept definition: risk is often only perceived as an unwanted, unfavourable consequence.

Such a definition embodies leads to two concepts: firstly, there is an established consensus among professionals that risk needs to be viewed as having both negative and positive consequence. Secondly; risk is not only related to events, i.e. single points of action, but also relates to future project conditions. Conditions may turn out to be favourable or unfavourable. This is because future project conditions are hard to predict in the early stages of the project life-cycle. In addition, conditions can change during the project lifecycle and the risk is that the conditions are different, and potentially more severe than was first estimated. Risks analysed only as certain events are further criticised for not considering the degree of impact. Risks are seldom one-off-types, meaning that risks either happen or do not happen. The impact of the risk varies greatly, depending on the conditions at the time of the possible occurrence (Finnerty et al, 2006). Variability and the level of predictability (uncertainty) of the future scenarios determine the quality of risk analysis done today.

Risk management is one of the most critical project management practices to ensure a project is successfully completed. Royer (2000) stated that experience has shown that risk management must be of critical concern to stakeholders and not just project managers, as unmanaged or unmitigated risks are one of the primary causes of project failure. Risk management is thus in direct relation to the successful project completion. Hence, evaluating and managing risks associated with variable construction activities has never been more important for the successful delivery of a project. Davies (2006) asserts that “construction projects are subject to risks at all stages of their development”. Planning permission can be hard to obtain and designs may not be complete even before the commencement of a project. These risks can be managed, minimised, shared, transferred or accepted but it cannot be ignored (Latham, 1994). Traditionally, the focus has been on quantitative risk analysis based on estimating probabilities and probability distributions for time and cost analysis. However, dissatisfaction arising from the inability of this type of approach to handle subjectivity in risk assessments has led to research into the use of other approaches. An approach that is preffered is for organisations to use risk quantification and modelling as tools to promote communication, teamwork and risk response planning amongst multidisciplinary project team members (Tar and Carr, 1999).

However, communication of construction project risks tends to be poor, incomplete and inconsistent, both throughout the construction supply chain and the full project lifecycle. Even when risk management is carried out, there is a tendency for it to be performed on an un-formalised ad hoc basis, which is dependent on the skills, experience and risk-orientation of individual key project stakeholders. This lack of formality and the use of risk management by individuals mean that the adoption of different methods and terminologies is not unusual.

This leads to the use of different methods and techniques for dealing with risk identification, analysis and management, thereby producing different and conflicting results. Risks identified are not rigorously examined and, even when they have been assessed and remedial measures agreed upon, they are not communicated effectively throughout the supply chain. As a result, project stakeholders lack a shared understanding of the risks that threatens a project and, consequently, unable to implement effective early warning measures and mitigating strategies to adequately deal with problems resulting from decisions that were taken without their knowledge. Part of the problem is the lack of a common language and process model in which remedial measures to risks may be identified, assessed, analysed and dealt with in a defined way (Tar and Carr, 1999). It is clear that the success of a project is dependent on the extent to which the risks affecting it can be measured, understood, reported, communicated and allocated accordingly.

1.2 STATEMENT OF PROBLEM

Risks are an inseparable part of every phase of the construction process (Makui, et al 2009). Risk in construction has been described as exposure of construction activities to economic loss, due to unforeseen events or foreseeing events for which uncertainty was not properly accommodated (Joshua and Jagboro, 2007). Whenever a construction project is embarked upon, there are some risk elements inherent in it, such as physical risk, environmental risk, logistics risk, financial risk, legal risk and political risk among others (Perry and Hayes, 1985). With construction projects becoming increasingly complex and dynamic in their nature as well as the introduction of new procurement methods, many contractors have been forced to have a rethink about their approach to the way that risks are treated within their projects and organisations.

This is because the current economic crises currently witnessed in the country due to falling oil prices and influx of new construction companies into the country due to global economic melt-down and the drive of foreign contractors to enter into new markets have increased the competition in the sector. The common risks challenges contractors battle with include changes in work, delayed payment on contract, financial failure of owner (client), labour and labour disputes, equipment and material availability, productivity of labour, defective materials, productivity of equipment, safety, poor quality of work, unforeseen site conditions, financial failure of contractor, political uncertainty, changes in legislation and policies, permits and ordinances, delays in resolving litigation/arbitration disputes, inflation, cost of legal process and force majeure (Zou et al 2007). In sum, there are problems of recurring conflict, client and stakeholder dissatisfaction from abandoned projects, and high accident rates. More so, when Nigeria needs to promptly address the infrastructural deficit currently affecting its economic development strategy. In other words, risk management therefore forms a basis for important decision making in procurement of construction projects; and the need to understand how construction contractors deliver projects within its planned objectives of time, cost, quality and safety in a peculiar environment cannot be overemphasized.

1.2 AIM

To develop a conceptual model for integrating competitive risk management practices in the procurement of construction and building services works in Nigeria from inception to completion.

1.3 OBJECTIVES OF STUDY

 To review existing risk management models with the aim of identifying a framework for mitigating peculiar risk management practices in Nigeria.

 To identify all challenges stakeholders contend with in the Nigerian construction industry.

 To conduct a quantitative assessment of contractors risk management practices in Nigeria.

 To conduct a case study of an ongoing project in the Nigerian construction industry to better understand the dynamics of uncertainty.

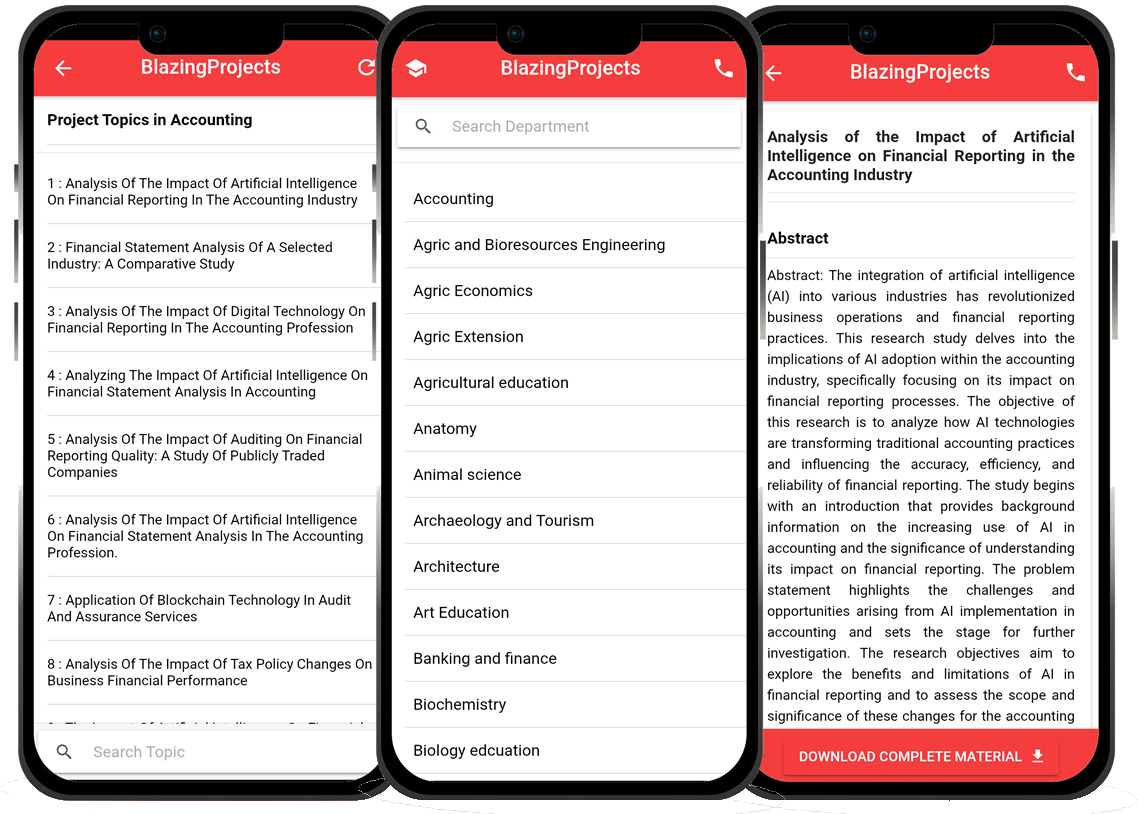

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Research Thesis

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Thesis-to-Journal Publication

🎓 Undergraduate/Postgraduate Thesis

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Energy-Efficient Building Design Using Sustainable Materials and Technologies...

The project titled "Energy-Efficient Building Design Using Sustainable Materials and Technologies" aims to explore the integration of sustainable mate...

Energy-Efficient Building Design Using Smart Technologies...

The project titled "Energy-Efficient Building Design Using Smart Technologies" focuses on exploring the integration of smart technologies to enhance e...

Implementation of Smart Building Energy Management System...

The project titled "Implementation of Smart Building Energy Management System" aims to address the growing need for more sustainable and efficient ene...

Implementation of Smart Building Automation System using IoT Technology...

The project titled "Implementation of Smart Building Automation System using IoT Technology" aims to explore the integration of Internet of Things (Io...

Development of an Energy-Efficient Smart Building System...

The project titled "Development of an Energy-Efficient Smart Building System" aims to address the growing need for sustainable and environmentally fri...

Integration of Renewable Energy Sources in Building Design for Enhanced Sustainabili...

The project titled "Integration of Renewable Energy Sources in Building Design for Enhanced Sustainability" aims to explore the integration of renewab...

Implementation of Green Building Technologies for Sustainable Construction Practices...

The project titled "Implementation of Green Building Technologies for Sustainable Construction Practices" focuses on the integration of environmentall...

Design and Implementation of a Smart Energy Management System for Residential Buildi...

The project titled "Design and Implementation of a Smart Energy Management System for Residential Buildings" aims to address the growing importance of...

Design and Construction of a Sustainable Green Building Using Recycled Materials...

The project titled "Design and Construction of a Sustainable Green Building Using Recycled Materials" aims to address the growing need for sustainable...