Nigerian curatorship and the exhibition of contemporary african art works

Table Of Contents

Declaration………………………………………………………………. ii

Certification……………………………………………………………. iii

Dedication……………………………………………………………… iv

Acknowledgements…………………………………………………….. v

Abstract……………………………………………………………….. vii

Table of Contents……………………………………………………… ix

Chapter 1

NATURE OF THE RESEARCH……………………………………… 1

1.0 Introduction……………………………………………………….. 1

1.1 Background……………………………………………………….. 1

1.2 Statement of the Problem………………………………………….. 3

1.3 Objectives of the Research………………………………………… 6

1.4 Justification of the Research………………………………………. 7

1.5 Significance of the Research………………………………………. 8

1.6 Research Questions and Hypothesis………………………………. 8

1.7 Scope and Delimitations of the Research………………………….. 8

Chapter 2

REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE……………………………… 10

2.0 Introduction……………………………………………………….. 10

2.1 Background……………………………………………………….. 10

2.2 Role of the Curator……………………………………………….. 15

2.3 Alternative Approaches to the Curation of Non-Western Art……… 16

2.4 Traditional Approaches to the Curation of Non-Western Art……. 18

2.5 Revisionist Approaches to the Curation of Non-Western Art…….. 23

9

2.6 Alternative Approaches by Non-Western Curators…….. 26

Chapter 3

METHODOLOGY………………………………………….. 28

3.0 Introduction………………………………………………. 28

3.1 Research Setting…………………………………………. 28

3.2 Research Design…………………………………………. 29

3.3 Methods of Data Collection and Analysis………………….. 31

3.4 Problems of Field Work………………………………….. 37

Chapter 4

ANALYSIS OF DATA AND DISCUSSION…………………. 39

4.0 Introduction……………………………………………… 39

4.1 Education and Curation in Nigeria………………………….. 39

4.1.1 Fine Art Course Curricula in Nigeria…………………….. 43

4.1.2 Relevance of Art History Course Content to Curation……….. 47

4.2 Experience and Curation in Nigeria…………………………. 52

4.3 Nigerian Curators in the West………………………………… 64

Chapter 5

SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS….. 71

5.0 Introduction………………………………………………. 71

5.1 Summary………………………………………………… 71

5.2 Conclusions……………………………………………….. 74

5.3 Recommendations………………………………………. 77

NOTES…………………………………………………………………. 79

BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………… 89

APPENDICES…………………………………………………………. 95

I Transcribed Oral Interview Schedules………………………………. 95

10

II Completed Questionnaires………………………………………….. 152

III Time Schedules for National Interviews, Table 1-2………………… 165

IV Bibliography of Exhibition Catalogue………………………………. 166

V Visual Sponsorship in Nigeria, Table 3……………………………… 168

VI Profiles of Participating International Curators………………………. 169

PLATES…………………………………………………………………. 28

I Map of Nigeria……………………………………………………….. 28

11

Thesis Abstract

The work of this thesis contributes to debates about cultural representation as it

relates to the exhibition of contemporary African art works. The central themes of

enquiry are the qualification and quality of Nigerian curatorship, and what

contributions Nigerian curators are making in the redefinition of contemporary African

art works, in light of the current debate into the misrepresentation of African art works

by Western curators. The focus of investigation is the extent to which provision for

curatorial scholarship is considered within course curriculums at institutes of higher

education within Nigeria, and the strengths and weaknesses of contemporary Nigerian

curatorial practice. The central questions taken for analysis are Why are so few

curators of Nigerian decent internationally recognised? Whose values and tastes

unfluence the Nigerian curators selection criteria? What is the value of indigenous

curators in the organisation of international exhibitions of contemporary African art

works? What can be done to encourage a new direction in the reception of

contemporary African art works? The hypothesis of the study is that “an indigenous

curator is best informed to curate exhibitions of contemporary art derived from his or

her own culture, and therefore should dominate in the organisation of such

exhibitions”. This hypothesis is examined with reference to the educational and

curatorial practice of Nigerian art lecturers working within Nigeria, and Nigerian

curators working both within and without of Nigeria.

The overall analysis is divided into three principal areas of investigation

“Education and Curation in Nigeria”, which addresses the question of what actually

7

qualifies someone as a curator of contemporary African art works in Nigeria. The

section refers to the personal views of Nigerian curators, the development of tertiary

course curriculums [and their content] in the visual arts and art history since their

inception, and concludes with a discussion of the relevance of current course content

to the area of curation and exhibition; “Experience and Curation in Nigeria”, then

looks at the experience of Nigerian curators, and the demands of the national

exhibition, with specific reference to the areas of location, identity, and aesthetic

values. Changes in exhibitionary practice is also addressed with particular attention

paid to the funding of projects, and the effect of both local and international patronage

on the art exhibition in Nigeria; the third area, “Nigerian Curators in the West”,

examines the curatorial practice of expatriate Nigerian curators, again with reference

to the areas of location, identity, and aesthetic values. The views of both national and

international curators are then given in reference to the role of African curators in the

diaspora and the exhibition of contemporary African art.

Findings indicated that although there exists a considerable exhibition culture in

Nigeria today, that professionality in the field is lacking. Although those interviewed

for the study were considerably active in the field, and exhibited a knowledge of

contemporary Nigerian art, the education and experience of these artist-curators was

inhibited by the limitations of current post graduate education in curation or related

fields of study, such as cultural representation, and also inadequate facilities and

funding for the actualisation of professional exhibitions. Finally, recommendations

centred on the provision of post-graduate courses in curation and related fields of

study, most appropriately as a masters degree programme, and further emphasised the

obligation of the Federal Government of Nigeria to encourage a greater professionality

in exhibition through the provision of repositories of art suitable for both national and

international exhibitions.

Thesis Overview

NATURE OF THE RESEARCH

1.0 Introduction

This chapter provides a synopsis of recent discourse concerning cultural

representation, from the late nineteen seventies to present. The information provided

clarifies the position, and genesis of the study, “Nigerian Curatorship and the

Exhibition of Contemporary African Art Works”, with specific argument regarding

cultural representation as it relates to the display of non-Western art works.

1.1 Background

It is generally recognised that Western scholarship (including art history) has

developed out of a history of conquest and expansion (political and commercial)1,

beginning with the first colonial initiatives of the eighteenth century2. This has left the

West in a dominant, central position, as opposed to the peoples [and their cultures] of

the South who are seen as peripheral. Although all societies create ideas of the “other”

to validate their own social boundaries and individual identities, the West is accused of

using concepts of a distant “other”3 in an effort to maintain its authority. By

designating the other as “underdeveloped”, “primitive”, “different”, “exotic” and

“static”4, the West has effectively denied any active or critical participation in

prevailing cultural practices. Today racial stereotypes continue to nurture unequal

power relations between the West and the “other” principally by means of receptacles

of modern learning, such as academic institutions and the popular media.

In relation to the reception of non-Western art works, the feelings of superiority

that emerged with colonialism are said to have privileged European collectors and

curators the authority to judge and define art works by their own criteria of value.

The conditions of visibility – what is seen, and how and when the other is seen – are

largely in their control. The tastes influencing such decisions have in turn been subject

12

to the racial and cultural stereotypes developed during the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries, when artifacts were first brought as bounty to the ethnographic halls of

Western museums5.

These artifacts were initially incorporated into Western art culture by means of an

anthropological presentation, and grouped art works would be contextualised with

labelling and visual aids to stress their function and [“tribal”] origin. Information

pertaining to an individual artist, such as name and date of production, was usually

omitted. Clearly, the emphasis was on the “authentic” artifact and how it relayed the

timeless traditions of a particular “tribe” rather than an individual work of art to be

appreciated as such. As anthropologist James Clifford (1997) concludes from literature

concerned with the early history of the exhibition of non-Western art: “It reveals the

racism, or at best the paternalist condescension, of spectacles which offered up mute,

exoticised specimens for curious and titillated crowds”6.

When the art of non-Western cultures was finally recognised as art rather than

artifact, at the beginning of the twentieth century7, it was still on Western terms.

Private gallery owners and art museum directors began to look to the formalist

aesthetics prescribed by the Western canons of “modernism”8 when judging, defining

and displaying art works. Selected art works were presented in isolation within the

white space of the modern art gallery in order that they would be appreciated as

individual pieces. However, again art works often remained authorless. For example,

the exhibition “Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the

Modern”, curated by William Rubin (1984), art works were left to speak for

themselves with contextualisation limited to ethnic labels alone.

These dominant positions to the exhibition of African art were most often applied

to the display of mainly “tribal” sculpture during the nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries. It was not until the 1980’s that the exhibition of modern African art was

13

given greater attention, dispite its considerable development within Africa since the

1960’s. Unfortunately, the majority of Western curators, have continued to show a

preference for art works that comply to the racial stereotype of an “authentic” African

art. That is, an art that would give the impression of an eternal, traditional culture very

different and distant to that of the progressive, advanced West. This authenticity has

largely been translated as the works of naive or self-taught artists in a perpetuation of

neo-primitivist exoticism9. As Emma Barker (1999) confirms, “Museums and galleries

are not neutral containers offering a transparent, unmediated experience of art”10.

Today, although in the guise of cultural recognition, “post-modernist”11

approaches to the exhibition of art from non-Western cultures continues to perpetuate

the stereotypes pertaining to the “other” in an active promotion of “difference”. Whilst

art critic Thomas McEvilley (1992) complains that Modernism fetishisizes sameness,

he also warns of a fetishization of difference in post-modern approaches to the

exhibition of art from non-Western cultures. Art works of non-Western cultures

appear to be little more than commodity, which if compatible with such stereotypes,

are highly marketable. As curator Richard Hilton (1999) says of the recent exhibitions

“Zero Zero Zero” and “Cities on the Move”: “Celebrating the other, be it global or

local, is tantamount to aestheticising difference for market expedience and, as such, it

has little to do with real empowerment”12.

1.2 Statement of the Problem

Since the mid 1980’s there has been a noticeable increase in the popularity of

temporary exhibitions of contemporary non-Western visual arts (including that of

African origins) in the West13. Today, contemporary African art can be viewed at a

number of international venues, including: museums, galleries, art workshops and a

number of public spaces. The majority of these often high-profile exhibitions14 have

continued to be shaped by a select group of Western curators, some of whom do not

even have qualifications in the field of art history, much less any specialisation in

14

African art. Curators currently influencing international art markets are largely made

up of anthropologists, and art collectors from the West. This is confirmed by art

historian Sidney Kasfir-Littlefield (1999): “. . . the tastes and preferences of a handful

of private collectors and the curators who work closely with them have had a great

influence on the way in which contemporary African art is being defined for its various

publics”15.

Often with little specialist knowledge of African artistic practice, and African

aesthetics, these curators are prone to rely on personal preferences when approaching

an exhibition, and these are in turn influenced by the social values of their own

cultures. Such personal decisions, based on Western tastes, values, and assumptions,

can give a misleading representation of contemporary African art that often

perpetuates racial stereotypes of the “other”. This is manifest in the constant stream of

survey type shows that confine the African artist to exhibitions of the “ethnic”

category, as representative of a homogeneous Africa. Selection processes for these

exhibitions further show an obsession for the art of the naive [non-academic] artist, at

the expense of artists who have passed through higher institutions of learning. The art

of the naive artist seems to demonstrate the sought after distance between the art of

Western scholarship and that of the African artist. This bias does not only give a

misleading portrayal of African art to the international viewer, but can also put

pressure on artists to invent identities that comply with the aesthetic values of the

dominant Western art market. As artist and critic Olu Oguibe (1993) contests: “ . .

African artists are either constructed or called upon to construct themselves”16. Critics,

including Picton (1993), Appiah (1997), and McEvilley (1992), [although they do not

dismiss the Western curator completely from partaking in the exhibition of non-

Western art], condemn those curators from the West who have used their own cultural

tastes as a standard to judge others [often with inhonourable motives], and ask for a

greater criticality of ones own tastes as well as an appreciation of those of others.

15

Until African artists are brought into the mainstream, as artists rather than African

artists, then these exhibitions of the “ethnic” category will persist. Many critics

[especially those of African decent] call for the increased participation of indigenous

curators in the exhibition of the art of their own cultures. The presumption is that selfdefinition

will open up the diversities of African art to the public, challenging and

expelling racial stereotypes, and subsequently recognising the individuality of artists

and allowing them to enter the mainstream. However, the current trend in exhibitions

of contemporary African art works seems to support the participation of African

artists and art historians only as co-curators or advisors, subordinates of their Western

counterparts. This seems to imply that Western curators are aware of their deficiency

in knowledge concerning African artistic practice. Despite this, few African curators

are seen to be challenging this inadequacy and making any significant impact on the

international exhibition circuit in their own right.

Patronage within and without of Africa has increased and diversified over the last

decade17, and therefore the assumption would be that indigenous curators have

emerged alongside these developments, with the capabilities, qualifications and

experience to supersede Western curators and begin to redefine African art on the

international circuit. The reasons for the lack of African curators working

internationally remains unclear, whilst Oguibe18 blames a closed circuit of Western

curators, others such as Nicodemus and Ogbechie19 seem to imply a lack of sufficiently

qualified or experienced professionals from Africa.

From within Africa complaints are arising over not only the rarity of

internationally recognised African curators, but also concerns are being voiced over

those curators who are currently visible, the majority of whom are made up of those

who have lived and worked in the West for many years. These curators are accused of

being unaware of current trends in the visual arts within Africa, instead promoting

African artists working outside of the continent, who are more conversant with, for

16

instance, the popular art of installation. This suggests again that a Western criteria of

value is taking preference. In view of this, the study will examine curation in Nigeria

largely by means of the evaluation Nigerian curators themselves, including the

individuals’ background and education, as well as his or her approach to curation and

experience in the field. The views of internationally active Nigerian curators will also

be assessed, especially in relation to differences between national and international

curation.

1.3 Objectives of the Research

This thesis sets out to examine the position of the Nigerian curator in relation to

the development of temporary exhibitions of contemporary African art. It is hoped that

this examination will suggest possible reasons why so few African curators are

recognised internationally: Whether this is a result of a lack of relevant experience or

education, or a deliberate exclusion on the part of Western art institutions [determined

to uphold the Western canon of art]. The manner in which Nigerian curators approach

the organisation of exhibitions will also be addressed, at both the national and

international level, in order to establish the values and tastes influencing the decisions

of these curators. This will help the researcher to determine the possible value of

indigenous curators in the organisation of international exhibitions of contemporary

African art works, and to suggest ways in which the status of the Nigerian curator may

be improved. The study hopes to answer these questions by:

1. Analysis of art course curriculum and content of the foremost institutions of

higher education in Nigeria.

2. Analysis of exhibition catalogues, journals, newspapers, internet sources and

official publications.

3. Analysis of supplementary secondary data, including that found in appropriate

textbooks.

17

4. Interviews with a sample of art lecturers and heads of departments of art at the

foremost institutions of higher education in Nigeria.

5. Interviews with a sample of Nigerian curators practising within Nigerian.

6. Questionnaires to be filled by a sample of Nigerian curators living and

working in the West.

1.4 Justification of the Research

Concern has been voiced over the way in which African art is being shaped by

exhibitions organised by an elite of Western curators. Many scholars have concluded

that local values and tastes must be recognised in order for a more honest

understanding to be proffered in exhibitions, freeing African artists from the pressure

to conform to Western preferences. This is endorsed by Barker (1999), who states

that: “The context of display is an important issue for art history because it colours our

perception and informs our understanding of works of art”20.

The authority of the curator: Who has the right to curate and how they curate,

must be addressed. It has been suggested that the way forward for exhibitions of non-

Western art is in a greater contribution to their curation by indigenous curators, art

historians, and artists themselves. However, although curators of African decent have

emerged over the last decade, such as the Nigerian born Okwui Enwezor, they remain

few in number, and under-represented at the international level. Through the opinions

and efforts of Nigerian artist-curators it is hoped that the study will be able to

determine who is best informed to curate African art, and if the way forward is in a

greater participation by African curators then why are so few curate internationally.

1.5 Significance of the Research

The temporary exhibition has become the principal medium for the distribution

and reception of art works, and largely determines the ways in which art is talked

18

about, understood and debated. The value of this study lies in the growing popularity

of exhibitions of contemporary African art.

The study will be of interest to all those involved in the study of non-Western art

markets, or concerned with the collection and display of contemporary African art

works. It is hoped that it will encourage institutions to become more sensitive to

issues pertaining to the reception of contemporary African art, such as the possible

potentials of a local knowledge, and to consider such issues when selecting curators

and curatorial teams. Furthermore, it is hoped that the study will encourage those

responsible for academic programmes in African institutions of higher learning to

consider the importance of courses in the field of cultural representation, such as

curation, and to review programmes where they are found lacking.

1.6 Research Questions

The questions to be addressed in this study are:

1. Why are so few curators of Nigerian decent internationally recognised?

2. Whose values and tastes influence the Nigerian curators selection criteria?

3. What is the value of indigenous curators in the organisation of international

exhibitions of contemporary African art works?

4. What is being done to encourage a new direction in the reception of African art?

1.7 Scope and Delimitations of the Research

The study will be delimited to Nigerian curators, and educators responsible for the

development of art programmes in Nigeria. The study will concentrate on the field of

curation from the 1980 to present, a time in which African art has become increasingly

popular in the West and questions of representation have been prompted. These

delimitations have been made in order to limit the problem and achieve a more potent

analysis as a result.

19

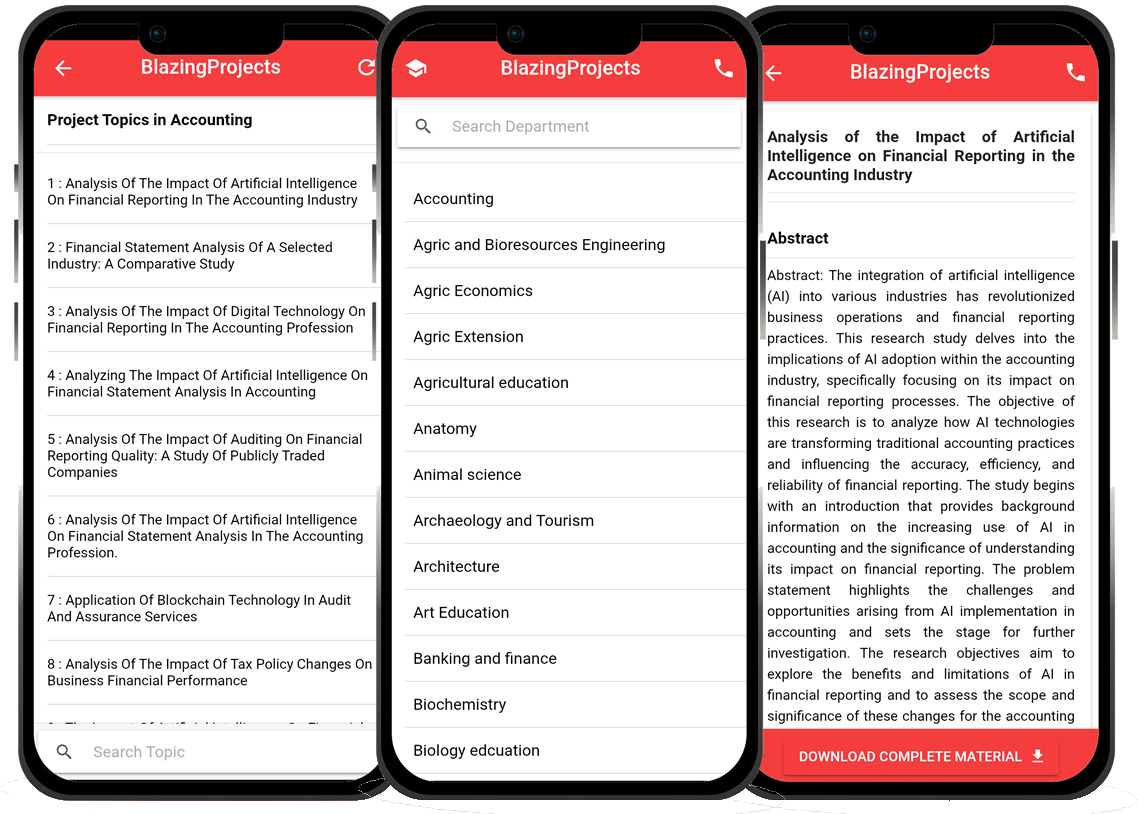

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Research Thesis

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Thesis-to-Journal Publication

🎓 Undergraduate/Postgraduate Thesis

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

The Impact of Technology on Traditional Art Techniques in Contemporary Design...

The project titled "The Impact of Technology on Traditional Art Techniques in Contemporary Design" delves into the intersection of technology and trad...

Exploring the Intersection of Technology and Traditional Art in Contemporary Design...

The research project titled "Exploring the Intersection of Technology and Traditional Art in Contemporary Design" seeks to investigate the dynamic rel...

The Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on Enhancing User Experience in Art Galleri...

The project titled "The Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on Enhancing User Experience in Art Galleries" aims to explore the influence of virtual r...

The Impact of Color Theory on User Experience in Graphic Design...

The project titled "The Impact of Color Theory on User Experience in Graphic Design" aims to investigate the significant influence that color theory h...

Exploring the Intersection of Technology and Traditional Art Techniques in Contempor...

The project titled "Exploring the Intersection of Technology and Traditional Art Techniques in Contemporary Graphic Design" aims to investigate how te...

Exploring the Intersection of Technology and Traditional Art Techniques in Contempor...

The project titled "Exploring the Intersection of Technology and Traditional Art Techniques in Contemporary Design" delves into the dynamic relationsh...

Exploring the Intersection of Technology and Visual Arts: Interactive Installation A...

The project titled "Exploring the Intersection of Technology and Visual Arts: Interactive Installation Art" delves into the dynamic relationship betwe...

The Impact of Virtual Reality on Art Appreciation and Creation...

The research project titled "The Impact of Virtual Reality on Art Appreciation and Creation" aims to explore the influence of virtual reality (VR) tec...

The Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on the Future of Art Exhibitions...

The research project titled "The Impact of Virtual Reality Technology on the Future of Art Exhibitions" aims to explore the intersection between virtu...