Alternative Foods as a Solution to Global Food Supply Catastrophes

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Alternative Foods2.2 History of Alternative Foods

2.3 Types of Alternative Foods

2.4 Nutritional Value of Alternative Foods

2.5 Environmental Impact of Alternative Foods

2.6 Global Consumption Trends of Alternative Foods

2.7 Economic Aspects of Alternative Foods

2.8 Cultural Perspectives on Alternative Foods

2.9 Future Prospects of Alternative Foods

2.10 Challenges and Opportunities in Alternative Foods

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Methodology Overview3.2 Research Design

3.3 Data Collection Methods

3.4 Sampling Techniques

3.5 Data Analysis Procedures

3.6 Ethical Considerations

3.7 Validity and Reliability

3.8 Limitations of the Methodology

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Analysis of Research Findings4.2 Comparison of Alternative Foods

4.3 Consumer Preferences and Behavior

4.4 Impact on Food Industry

4.5 Sustainability of Alternative Foods

4.6 Policy Implications

4.7 Recommendations for Future Research

4.8 Implications for Global Food Security

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Findings5.2 Conclusions

5.3 Contributions to Knowledge

5.4 Practical Implications

5.5 Recommendations for Action

Thesis Abstract

ABSTRACT

Analysis of future food security typically focuses on managing gradual trends such as population growth, natural resource depletion, and environmental degradation. However, several risks threaten to cause large and abrupt declines in food security. For example, nuclear war, volcanic eruptions, and asteroid impact events can block sunlight, causing abrupt global cooling. In extreme but entirely possible cases, these events could make agriculture infeasible worldwide for several years, creating a food supply catastrophe of historic proportions. This paper describes alternative foods that use non-solar energy inputs as a solution for these catastrophes. For example, trees can be used to grow mushrooms; natural gas can feed certain edible bacteria. Alternative foods are already in production today, but would need to be dramatically scaled up to become the primary food source during a global food supply catastrophe. Scale-up would require extensive depletion of natural resources and difficult social coordination. For these reasons, large-scale use of alternative foods should be considered only for desperate circumstances of food supply catastrophes. During a catastrophe, alternative foods may be the only solution capable of preventing massive famine and maintaining human civilization. Furthermore, elements of alternative foods may be applicable to non-catastrophe times, such growing mushrooms on logging residues. Society should include alternative foods as part of its contingency planning for food supply catastrophes and possibly during normal times as well.

Thesis Overview

Despite technical advancements and an abundance of food globally, food security is a major ongoing challenge. 870 million people do not have enough to eat and under-nutrition contributes to the premature deaths of over six million children annually.1 Land degradation, fresh water scarcity, overfishing, and global warming all threaten to diminish food supplies. Food demand is meanwhile increasing due to population growth and a rising middle class in the developing world that can purchase more and different foods. Improved technologies have helped farmers grow more, but extreme wealth inequality still leaves the world’s poorest struggling to afford enough food. These and other trends virtually guarantee that feeding humanity will require major dedicated effort into the future. But it gets worse. These trends show gradual shifts in food security under otherwise “normal” circumstances. However, a range of extreme events could cause large abrupt declines in global food production from conventional agriculture.2 If one of these events occurs, humanity could face global famine of historic proportion. The collapse of human civilization or even the extinction of the human species are distinct possibilities. Other species around the world would likely also go extinct, including species that would otherwise survive the extinction event already underway. One major threat comes from events that block sunlight by sending large quantities of dust, smoke, or ash into the atmosphere. This could happen if Earth collides with a large asteroid or comet, such as the one believed to have caused the dinosaurs’ extinction. It could also happen from a supervolcanic eruption, such as the Toba eruption 75,000 years ago that some scientists propose almost killed off our early human ancestors.3 And it could happen from a nuclear war, with the atmosphere coated by the ashes of incinerated cities. Some abrupt food supply threats come from rapid environmental change or direct threats to crops. These food catastrophes may not be as severe as the sun-blocking catastrophes, but they can still cause large and abrupt declines in food production. Global warming could cross thresholds in the Earth system.4 For example, a rapid change in ocean circulation could bring dramatic shifts in global weather patterns. Specific crops can be threatened by natural pests, as in the Irish Potato Famine. Biotechnology could bring even more devastating engineered crop pathogens. For comparison, biosecurity experts are actively debating the potential for certain “gain-of-function” experiments to cause deadly human pandemics.5 Similar research may be able to bring crop pandemics. And these are just some known scenarios. Additional threats may lurk beyond the current horizon of science. As an illustration of how bad things could get, consider one scenario, a nuclear war between India and Pakistan. Smoke from the burning cities would block sunlight and reduce global temperatures by about 1ºC for about a decade.6 Crop simulations project food production declines around 20% to 50%.7 Combining that with existing poverty and malnourishment gives an estimated two billion people at risk of starvation.8 And that is for a war with “only” 100 nuclear weapons. A war using more of the world’s 15,800 nuclear weapons would bring even worse consequences. There are several solutions for abrupt global food catastrophes. If agriculture is still possible, it can be diverted from livestock and biofuels production to direct human consumption, though larger catastrophes would leave less food to divert. Additional food could also come from oceans, though this a limited option and it could further threaten marine biodiversity. Another solution is to stockpile food prior to the catastrophe, though this is expensive and it can worsen pre-catastrophe food security. In light of the enormous threat of global food supply catastrophe and the shortcomings of other solutions, we propose a new solution. The essence of it is to produce food with energy from sources other than the Sun. Ultimately, crops do not need sunlight per se. They just need energy. We call our solution “alternative food” because it uses alternatives to sunlight, just like “alternative energy” uses alternatives to fossil fuels. Alternative foods are already in limited production and could be scaled up following a major catastrophe.9 The simplest type of alternative food is plants grown from artificial light. Today, indoor agriculture powered by light-emitting diodes is being explored as a solution to land scarcity and resource-intensive outdoor agriculture.10 These indoor farms could produce any of the crops currently grown around the world. However, a lot of energy is lost converting the initial energy source into electricity, then into light, then into plants. As a result, all of the world’s electricity could feed only a small portion of the world’s population. To feed everyone, other solutions are needed.

A better solution comes from foods powered by fossil fuels. Today, the company Unibio grows bacteria from natural gas and sells it as livestock feed.11 The same livestock could feed some people after a catastrophe. More people could be fed by adapting the Unibio process for direct human consumption. Our prior research on this has prompted charming headlines like “Bacterial slime: It’s what’s for dinner”.12 But as odd as it might seem, getting food from bacteria could keep many people alive in a catastrophe. So too for other techniques using natural gas or other fossil fuels. And thanks to progress in food science, the resulting foods may even taste good. A different energy source does not need so much infrastructure: biomass. After a catastrophe, biomass would be available from the trees and other plants that are still around. Biomass could be harvested by foraging or lumbering. Collecting a lot of biomass could damage ecosystems, creating another tradeoff. However, this tradeoff would only be faced in the event of a food catastrophe. Furthermore, if the sun is blocked, then some or all of the trees would die anyway, depending on how much of the sun is blocked. This makes alternative foods from biomass an especially attractive solution. Biomass can be fed into the food supply in several ways, as illustrated in the food web. Wood can be fed to beetles, which can in turn be fed directly to humans or to a more appetizing intermediate species. Using an intermediate species would greatly reduce the amount of food available to humans. Horses, cows, goats, and sheep can be fed leaves and non-woody plants. Mushrooms can grow on all of the above types of biomass. Finally, if woody biomass is partially consumed by mushrooms or bacteria, this could be fed to rats or even chickens.

Some plants and plant parts can be fed directly to humans. Familiar foods include nuts and edible leaves. Less familiar options could also help during a food catastrophe. Some leaves (such as pine needles) can be boiled to make tea. Some biofuels turn cornstalks and other residues into sugar with enzymes. Then the sugar is fed to a fungus to make ethanol. But if people are short on food, they could just eat the sugar. Biomass foods cannot provide everything found in a grocery store, but they can keep people from starving to death. Some of these techniques can even improve food security during “normal” times, such as by feeding sawmill wood waste to mushrooms. As the food web illustrates, the waste from one organism can become the food for another organism The best solutions for abrupt food catastrophes will vary from place to place.13 Local social and environmental factors are important. Some places have more energy for indoor agriculture, or more biomass, or more fossil fuels. Some places have technical and political capacity that is better suited for certain solutions. Some places have cultural preferences for certain types of foods. For these and other reasons, food catastrophe solutions should be developed locally, to ensure that each community has a solution that works for itself.

There is another reason to develop these solutions locally. In the aftermath of a major global catastrophe, regions could become isolated from each other. Travel, trade, and communications all depend on complex systems of infrastructure. A catastrophe big enough to damage global agriculture could also disrupt these systems, though agriculture will usually be more sensitive to environmental catastrophes than most built physical infrastructure. Self-sufficient communities will be best positioned to weather out the storm.14

Finally, the solutions presented here could also be used to protect biodiversity. Plant biodiversity is relatively easy to preserve by storing seeds, such as in the Svalbard “doomsday” seed vault. Protecting animal biodiversity is harder. For that, alternative foods can help. If no food is available in the wild, humans could divert some alternative foods to preserving nonhuman animal species. It would be impossible to keep every animal alive, but it should be possible to keep each species from going extinct. As few as 100 individuals can be enough to prevent a species from going extinct. 100 individuals per species could be fed without any significant loss to the human food supply. Therefore, in addition to keeping many or even all humans alive, alternate foods could save most of the animal biodiversity that would have been lost in a catastrophe. Everyone should hope that no abrupt global food supply catastrophe ever occurs. But while people should hope for the best, they should prepare for the worst. Alternative foods are a solution that could keep millions or billions of people alive during even the most severe food catastrophes. They require only modest advance preparation and no diverting of food into stockpiles. Indeed, alternative foods can even strengthen food security now by opening up new means for food production and using resources more efficiently. For these reasons, and given the extremely high stakes with abrupt global food supply catastrophes, we believe alternative foods are a solution well worth pursuing.

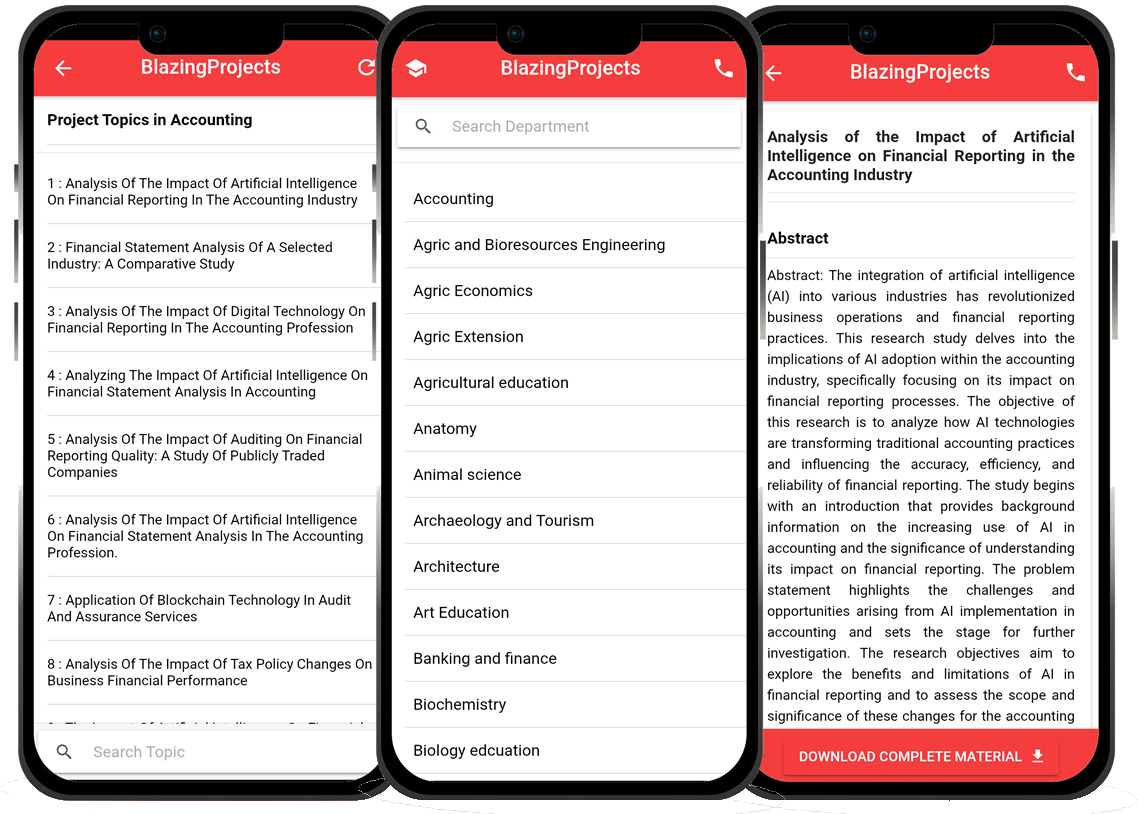

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Research Thesis

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Thesis-to-Journal Publication

🎓 Undergraduate/Postgraduate Thesis

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Design and development of an automated irrigation system for precision agriculture i...

The project titled "Design and Development of an Automated Irrigation System for Precision Agriculture in Crop Production" aims to address the increas...

Design and Development of an Automated Irrigation System for Sustainable Crop Produc...

The project titled "Design and Development of an Automated Irrigation System for Sustainable Crop Production" focuses on addressing the challenges fac...

Design and Implementation of an Automated Irrigation System for Precision Agricultur...

The project titled "Design and Implementation of an Automated Irrigation System for Precision Agriculture" aims to address the challenges faced in tra...

Design and Development of an Automated Irrigation System for Precision Agriculture i...

The project titled "Design and Development of an Automated Irrigation System for Precision Agriculture in Crop Production" aims to address the growing...

Design and Development of an Automated Irrigation System for Sustainable Crop Produc...

The project titled "Design and Development of an Automated Irrigation System for Sustainable Crop Production" aims to address the crucial need for eff...

Design and Development of an Automated Irrigation System for Precision Agriculture i...

The project titled "Design and Development of an Automated Irrigation System for Precision Agriculture in Crop Production" focuses on the utilization ...

Design and Development of an Automated Irrigation System for Crop Production...

The project titled "Design and Development of an Automated Irrigation System for Crop Production" aims to address the need for efficient and sustainab...

Optimization of Irrigation Systems for Sustainable Crop Production in Arid Regions...

The project titled "Optimization of Irrigation Systems for Sustainable Crop Production in Arid Regions" aims to address the critical need for efficien...

Design and development of an automated irrigation system for precision agriculture....

The project titled "Design and development of an automated irrigation system for precision agriculture" aims to address the growing need for efficient...