Farm power and mechanization for small farms in sub-Saharan Africa

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of Study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of Study

1.5 Limitation of Study

1.6 Scope of Study

1.7 Significance of Study

1.8 Structure of the Research

1.9 Definition of Terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Farm Power2.2 Historical Perspectives on Mechanization

2.3 Importance of Mechanization in Agriculture

2.4 Types of Farm Machinery

2.5 Adoption of Farm Power Technologies

2.6 Challenges in Implementing Mechanization

2.7 Economic Impact of Mechanization

2.8 Environmental Implications

2.9 Social Aspects of Mechanization

2.10 Future Trends in Farm Power and Mechanization

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Design3.2 Population and Sampling Techniques

3.3 Data Collection Methods

3.4 Data Analysis Procedures

3.5 Research Ethics

3.6 Reliability and Validity

3.7 Limitations of the Methodology

3.8 Research Assumptions

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Overview of Findings4.2 Analysis of Data

4.3 Comparison of Results with Literature

4.4 Interpretation of Findings

4.5 Discussion on Implications

4.6 Recommendations for Practice

4.7 Suggestions for Future Research

4.8 Conclusion of Findings

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Research5.2 Conclusions Drawn

5.3 Contributions to Knowledge

5.4 Practical Implications

5.5 Areas for Future Research

Thesis Abstract

ABSTRACT

According to the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), 200 million people in Africa, or 28 percent of the continent’s population, were chronically hungry in 1997–99. By the end the 1990s, only ten countries had been able to reduce their numbers of hungry people in that decade. Food imports have been rising since the 1960s, and Africa became a net agricultural importer in 1980. The agriculture sector now provides only 20 percent of the continent’s exports, whereas it provided 50 percent in the 1960s. NEPAD makes agriculture one of its main priorities “as the engine of NEPADinspired growth”. It stresses three aspects improving the livelihoods of people in rural areas; achieving food security; and increasing exports of agricultural products. None of these aims can be achieved without giving serious attention to family farm power in small-scale agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Farm power is a vitally important component of small farm assets. A shortage of farm power seriously constrains increases in agricultural productivity, with a resultant stagnation in farm family income and the danger of a further slide towards poverty and hunger. Studies in SSA in 2003 and 2004 have revealed in a graphic manner that unless the issue of farm power is addressed in a practical way, with solutions that are accessible to small farmers, the region is at risk of increasing poverty and hunger. The Millennium Development Goal of halving the proportion of people suffering extreme poverty by 2015, and the similar goal of the World Food Summit in 1996 to reduce the number of starving people by half, are now unlikely to be attainable in SSA until well into the 21st century. The review and guidelines presented in this publication are the result of several recent studies of the power situation of farm families in small-scale agriculture in SSA. These reports reconfirm that the farm power situation is deficient almost everywhere, and that urgent measures are needed to correct it if the widely promoted goals of raising the productivity of the sector, reducing poverty, and achieving food security are to be achieved. Another serious concern in SSA is that of soil degradation. The level of degradation varies considerably across the region and is difficult to quantify. However, some figures for soil erosion in Ethiopia were documented in 1988; they ranged from 16 to 300 tonnes of soil per year being washed away, with an average for the country of over 40 tonnes/year on cultivated land. An FAO/World Bank Ethiopian Highlands Reclamation Study some four years earlier estimated that 1 900 million tonnes of soil a year were being washed away from the cultivated land in the Highlands, equivalent to about 100 tonnes per ha. Even if the erosion rate were halved, there would still be a 2 percent per year reduction in total grain production in the Highlands. It is true that erosion and soil degradation in Ethiopia are particularly severe, but in many other parts of Africa there is abundant anecdotal evidence from smallholders themselves who state that they are obtaining much smaller yields from a particular plot than were being obtained by their fathers and grandfathers. There can be little doubt that conventional methods of farming, with much soil disturbance for seedbed preparation, exacerbate erosion. This and the depletion of soil organic matter and nutrients contribute to soil degradation. Any interventions concerning farm power and farming systems need to take into account the issue of soil degradation; at the very least, they must contribute to halting the degradation process, or better still, reversing it.

Thesis Overview

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND

The eradication of extreme poverty and hunger is the first of the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals. By 2015, as a first step, the objective is to have reduced by half the proportion of people living on less than a dollar a day, and also to have reduced by half the proportion of people who suffer hunger, in line with the World Food Summit Resolution of 1996. In sub-Saharan Africa, the escalating levels of poverty and underdevelopment, and the continued marginalization of the African continent in general, constitute enormous challenges that call for urgent and energetic actions if the 2015 objectives are to be met. Indeed, the prospects for doing so are already looking grim, with the UNDP Human Development Report of 2003 stating that the 2015 objectives would probably only be attained well into the 21st century in subSaharan Africa (SSA). It was precisely because of this gloomy outlook and the need for energetic action that a number of African leaders, and the OAU, took the initiative of creating the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD). This amounts to a radical intervention, spearheaded by African leaders, to develop a new vision and strategic framework for that will ensure Africa’s renewal. Agriculture is one of NEPAD’s six priorities, and agriculture is seen as the engine of NEPADinspired growth, beginning with the aims of improving the livelihood of people in rural areas, achieving food security, and increasing exports from the sector. It is explicit in NEPAD’s strategy that growth in the agricultural sector will stimulate growth in other economic sectors. Agricultural productivity needs to be greatly enhanced if the sector is to play the role expected of it by NEPAD. Some figures illustrate the magnitude of the challenge being faced. NEPAD’s documentation states that in 1997–99, there were 200 million chronically hungry people in Africa, representing 28 percent of the total population.

Furthermore, the situation is deteriorating, for in the seven or so years (from 1990–92) leading up to 1997–99 there was an increase of 27 million hungry people. During the 1990s, only ten African countries reduced their number of chronically hungry people. At the end of the 1990s, 20 percent of the population in 30 countries were undernourished, while in 18 of those countries, as much as 35 percent of the population was similarly afflicted. In 2001, 28 million people were facing food emergencies. Since the 1960s, food imports into Africa have been rising steadily, and the continent became a net importer of agricultural produce in 1980. Agriculture in Africa employs 60 percent of the labour force and produces just 20 percent of exported merchandise, while it was 50 percent in the 1960s. NEPAD sums up its view of the importance of the agricultural sector in these words: Until the incidence of hunger is brought down and the import bill reduced by raising the output of farm products, which the region can produce with comparative advantage, there is no way in which the high rates of economic growth to which NEPAD aspires can be attained. (From the summary of NEPAD Action Plans).

1.2 THE CRUCIAL ROLE OF FARM POWER

The review and guidelines presented in this publication are the result of several recent studies on the farm family power situation in small-scale agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). These reports reconfirm many earlier studies to the effect that the farm power situation is deficient almost everywhere and that urgent measures are needed to correct it. In fact, the increases in agricultural productivity required in SSA to meet the MDG and NEPAD objectives will not be achievable without giving very serious attention to the issue of family farm power in small-scale agriculture. Farm power is a vitally important component of small farm assets, and a shortage of it lies at the heart of many of the problems of smallscale farming in SSA.

If the major constraint of farm power cannot be lifted, there will be little increase in agricultural productivity, stagnation in farm family income, more hunger, and less food security. Nor will it be possible for agriculture to become “the engine of NEPAD-inspired growth” that will also “stimulate growth in other economic sectors”. In brief, unless the farm power shortage is overcome, there is a danger that rural people in SSA will face a further slide into poverty and hunger, while their national economies remain stunted. Studies in SSA (Bishop-Sambrook, 2005; Kienzle, 2003; Ribeiro, 2004) have revealed in a graphic manner that unless the issue of farm power is addressed in a practical way, with solutions that are accessible to small farmers, the region is at risk of increasing poverty and hunger. Labour shortages in the agricultural sector of SSA have been a growing problem in recent decades. One factor creating those shortages is migration – mainly of men – to seek work in towns because their farming activities have been unable to provide a decent livelihood for them and their families.

A second factor is HIV/AIDS, which started out as a mainly urban problem in SSA, initially affecting more men than women, and those with relatively high incomes. Now, however, it has moved rapidly into the rural areas. It is estimated that by 2020, the epidemic will have claimed the lives of 20 percent or more of all those working in agriculture in many Southern African countries (FAO, 1995). Clearly, since AIDS mostly devastates the productive age group – people between 15 and 50 – it has a severe effect on a household’s labour availability, and hence on its productive capacity. But it is not only the loss of life to AIDS that effects labour availability and agricultural productivity. Some of the other effects of the AIDS epidemic are: AIDS sufferers often cannot work during bouts of related sickness and need care and support from another household member; once households experience labour shortages caused by AIDS, they are often unable to participate in the labour groups that are commonly mobilized for key farming operations; and finally, in extreme circumstances, households sell their productive assets, such as draught animals, tools, and implements, to raise cash (FAO, 1995).

Another serious problem affecting agricultural productivity in SSA is that of soil degradation. The level of degradation varies considerably across the region and is difficult to quantify. However, some figures for soil erosion in Ethiopia have been documented, ranging from 16 to 300 tons of soil per year being washed away, with an average for the country of over 40 tons/year on cultivated land (Hurni, 1988). A World Bank/ FAO study four years earlier estimated that even if the erosion rate were halved, there would still be a 2 percent per year reduction in total grain production in the Ethiopian Highlands. Erosion also carries away plant nutrients, as does cropping without replacing soil nutrients with fertilizer, sometimes termed “mining” of nutrients. An influential body of opinion holds that the fertility of soils in SSA is declining, and it is true that crop yields per hectare are falling. However, there can also be political and social reasons for this, as well as the expansion of crop production into less favourable areas. There is considerable debate on the subject (DDPA, 2005; Campbell, 2005). Nevertheless, there is abundant anecdotal evidence in many parts of Africa from smallholder farmers themselves who state that they are obtaining much smaller yields from a particular plot than were being obtained by their fathers and grandfathers.

There can be little doubt that conventional methods of farming, with much soil disturbance for seedbed preparation, leave the soil prone to erosion. Conventional soil tillage also speeds the depletion of soil organic matter and nutrients, contributing to soil degradation. Any interventions concerning farm power and farming systems need to take into account the issue of soil degradation; at very least, they must contribute to halting the degradation process, or better still, to reversing it.

1.3 MECHANIZATION FOR SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT

Agricultural mechanization has been defined in a number of ways by different people. Perhaps the most appropriate definition is that it is the process of improving farm labour productivity through the use of agricultural machinery, implements and tools. It involves the provision and use of all forms of power sources and mechanical assistance to agriculture, from simple hand tools, to animal draught power (DAP), and to mechanical power technologies. Mechanization is a key input in any farming system. It aims to achieve the following: • improved productivity of labour;

• a reduction of drudgery in farming activities, thereby making farm work more attractive;

• an expansion of the area under cultivation where land is available, as it often is in SSA;

• increased productivity per unit area as a result of improved timeliness of farm operations;

• accomplishment of tasks that are difficult to perform without mechanical aids;

• improvements in the quality of work and of products.

Based on the source of power, the technological types of mechanization have been broadly classified as hand-tool technology, DAP technology, and mechanical power technology. Sophistication, capacity to do work, costs, and in some cases precision and effectiveness, determine the levels of efficiency that can be achieved in each system. One of the major reasons for the disappointing performance and contribution of mechanization to agricultural development in SSA has been the fragmented approach to it (Rijk 1989; Mrema and Odigboh, 1993, Simalenga 1997). This often arises from poor planning and an over reliance on mechanization inputs that are provided as aid-in-kind from donors and prove unsuitable for local conditions.

Poor co-ordination within and between government agencies and the private sector dealing with mechanization have compounded the problems. The formulation of national agricultural mechanization strategies can help to overcome these constraints. A holistic or system analysis approach is required in the planning process, and all the key players in the economic and cultural environment in which development is to take place must be considered. The type and level of mechanization in a particular area should initially be guided by the producers of mechanization inputs, both to suit their business and to meet their clients’ particular needs and circumstances. However, the process of making mechanization choices should bring farmers in as the focus of policy, planning, and development.

1.4 THE SCOPE AND PURPOSE

The purpose of this publication is to provide information and guidelines for policy makers in agricultural and rural development and for regional and district staff with responsibilities in this area. The Executive Summary will perhaps be the most appropriate for policy makers, while the rest of the publication provides more detailed information and guidelines for planning and implementing farm power and mechanization initiatives. The power sources and operations covered in this document are the following:

• human, animal, and tractor power sources

• land preparation, weeding, ridging, crop harvesting, and threshing

• small-scale irrigation technology based on human-powered water pumping.

The publication does not address the whole spectrum of farm power and mechanization options for smallholder farmers in SSA. Such a document would need to be greatly expanded and would include pest control, crop processing, transport, and irrigation, as well as a consideration of alternative power sources, such as water, wind, and sun. The document is structured to provide an overview of farm power and farming systems in sub-Saharan Africa (Chapter 2), followed by an examination of how farm power affects agricultural productivity and rural livelihoods (Chapter 3). These considerations set the scene for a discussion on technological options in farm power, covering means of increasing its availability but also of reducing the need for it through agricultural production systems that call for low inputs of energy (Chapter 4). The household-level financial and economic implications of farm power options are then explained (Chapter 5), followed by a description of participatory approaches to mechanization planning and evaluation (Chapter 6). The publication ends with policy and operational guidelines, and also considerations for creating an enabling environment for fostering solutions to the problems power on small-holder farms in SSA (Chapter 7).

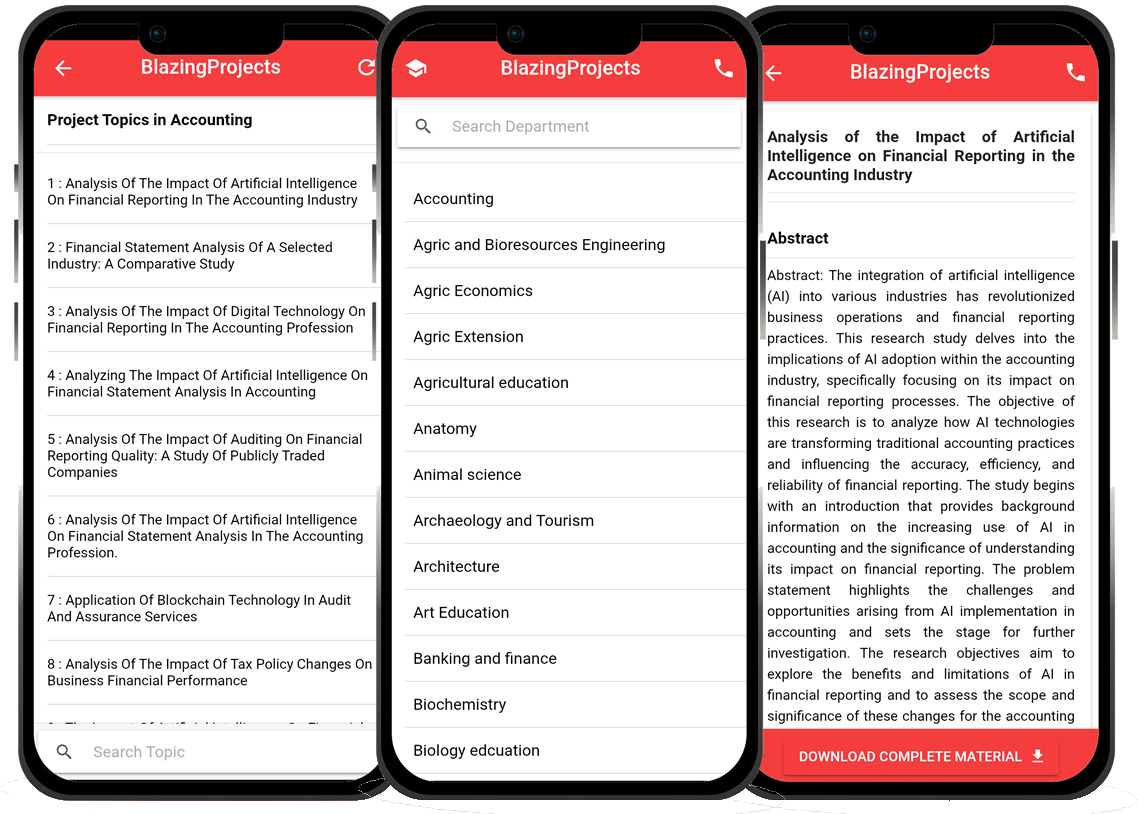

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Research Thesis

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Thesis-to-Journal Publication

🎓 Undergraduate/Postgraduate Thesis

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities...

The project titled "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" aims to explore the potential of mobile tech...

Utilizing Information and Communication Technologies for Enhancing Agricultural Exte...

The project titled "Utilizing Information and Communication Technologies for Enhancing Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" aims to e...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Enhancing Agricultural Extension Services in Rural C...

The project titled "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Enhancing Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" aims to explore the potential bene...

The impact of digital technology on improving agricultural extension services....

The project titled "The impact of digital technology on improving agricultural extension services" aims to investigate how the integration of digital ...

Utilizing Technology for Effective Agricultural Extension Services: A Case Study in ...

The project titled "Utilizing Technology for Effective Agricultural Extension Services: A Case Study in a Rural Community" focuses on the integration ...

Assessing the Impact of Mobile Technology on Agricultural Extension Services in Rura...

Research Overview: The project titled "Assessing the Impact of Mobile Technology on Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" aims to inv...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Effective Agricultural Extension Services in Rural C...

The project titled "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Effective Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" aims to explore the potential of m...

Utilizing Mobile Technology for Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities...

The project titled "Utilizing Mobile Technology for Agricultural Extension Services in Rural Communities" focuses on leveraging mobile technology to e...

The Impact of Digital Technologies on Agricultural Extension Services: A Case Study ...

The research project titled "The Impact of Digital Technologies on Agricultural Extension Services: A Case Study in a Rural Community" aims to investi...