IMPACT OF KOGI STATE SURVIVAL FARMING INTERVENTION PROGRAMME ON CASSAVA PRODUCTION IN THREE LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS, KOGI STATE, NIGERIA

Table Of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Title Page……………………………………………………………………...........................................…...……...ii

Declaration……………………………………………………………………….............................................……iii

Certification……………………………………………………………………...........................................…......…i

Dedication…………………………………………………………………………................................................…v

Acknowledgements………..………………………………………………………..............................................vi

Table of Contents……………………………………………………………...…...............................................viii

List of Tables……………………………………………………………………..................................................xii

List of Figures…………………………………………………………….…….…............................................xiii

Abstract……………………………………………………………………................…..…........................…....xiv

Chapter ONE

: ..…………………………………………………………………...........................................….1

INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………..……..……...…..........................................…..1

1.1 Background of the Study………………………………………………………...................................….....1

1.2 Problem Statement………………………………………….………………….............................................4

1.3 Objectives of the Study……………………………………………..……………....................................….8

1.4 Justification of the Study……………………………………………..……...................................…….….8

1.5 Hypotheses…………………………………………..………….…….......................................…………...…9

Chapter TWO

: …..…………………………………………...........................................……………………….10

LITERATURE REVIEW………………………..………………………...………...........................................…...10

2.1 Socio-economic Characteristics of Smallholder Farmers……………….…............................……….10

2.2 Level of Awareness of Agricultural Innovations by Smallholder Farmers..…..........................…….14

2.3 Factors Influencing Adoption of Recommended Practices………………….............................….….17

2.4 Cassava Production in Nigeria…………………………...................................….…………………...…..19

2.5 Rural Household Income……………………………….....................................…………………………..22

2.6 Rural Livelihoods and Their Natures…………………………..................................……………………24

2.7 Agricultural Intervention Projects in Nigeria……………………………..........................……......…....26

2.8 Constraints Faced by Smallholder Farmers in Agricultural Programmes…......................….…....28

2.9 Constraints in Implementation of Agricultural Intervention Projects in Nigeria….......................29

2.10 Theoretical Framework of the Study……………………………………...............................…….….31

2.10.1 The adoption and diffusion theory……………...……………………………..................................31

2.10.2 The impact assessment perspectives……………….…………………….……..............................33

2.11 Conceptual Model…………………………………………………………....................................….….34

Chapter THREE

: ..………………………………………………………........................................………..36

METHODOLOGY……………………………………………….………..……......................................……..36

3.1 Study Area……………………………………………………………......................................…………..36

3.2 Sampling Procedures and Sample Size………………………………...............................….…..........38

3.3 Sources of Data………………………………………………………….....................................…………40

3.4 Analytical Tools……………………………………………………………...................................................40

3.5 Model Specifications……………………………………………………….….......................................…...41

3.5.1 Logit regression analysis………………………..………………………...…....................................…..41

3.5.2 Chow-test statistic…………………………….………………………………......................................…42

3.6 Operationalization and Measurement of Variables………………………….…………………... ……..43

3.6.1 Measurement of independent variables…………………………… ………………………………… 43

3.6.2 Measurement of dependent variables………………………………………………………… ……...46

Chapter FOUR

: …………………………………………………….....…………………………

…………...47

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION…………………..………………… ………………………… …………….…47

4.1 Socio-Economic Characteristics of the Respondents……………………………………………

…….47

4.1.1 Age of the respondents…………………………………………… ………………………… …………..…47

4.1.2 Marital status of the respondents………………………………………… ……………………… ….…..47

4.1.3 Gender of the respondents…………………………………….....................…………………… ……….48

4.1.4 Educational qualification of the respondents………………… ………………………………… …….48

4.1.5 Farming experience of the respondents…………………… ………………………………… ….....49

4.1.6 House-hold size of the respondents……………………………………… …………………… ….......49

4.1.7 Labour usage of the respondents………………………………………….......…………………… .....51

4.1.8 Farm size of the respondents…………………………………………… ……………………… ……….51

4.1.9 Land ownership of the respondents…………………………………………………………… ……......52

4.1.10 Access to credit on cassava production……………………………… …………………… ………..53

4.1.11 Sources of credit to the respondents…………………………………... ……………………………… 54

4.1.12 Extension visits to the respondents…………………………………………………………… …….....54

4.1.13 Cooperative membership of the respondents……………………………………………… ……......55

4.2 Level of Awareness of SFIP Components……………………………………………………………

…......55

4.2.1. Awareness of SFIP components by the respondents………… ………………………………… ......56

4.2.2 Sources of awareness of SFIP components by the respondents…....… ……………………… ..56

4.2.3 Components of SFIP benefited by the respondents………………… ………………… …...…….57

4.2.4 Level of awareness of SFIP base on its components……...... ………………………………… .….58

4.3 Factors Influencing Participation in SFIP on Cassava Production……………………………… .….59

4.4 Impact of Survival Farming Intervention Programme……… …… ………………………………… …..61

4.4.1 Impact of SFIP on Cassava Output………………………………………………… ……………..61

4.4.2 Impact of SFIP on Cassava Yield………………………………………………………… ………….…62

4.5.1 Impact of SFIP on Income……………………………………………....………....................................63

4.5.2 Impact of SFIP on Level of Living………………………………/...................................................….64

4.5.3 Sources of livelihood of the respondents………………………………….…

………………….

…65

4.5.4 Perceived living conditions of the respondents……………… …………………. …………....…...66

4.6 Constraints of the Farmers in Accessing SFIP…………………………..................................………67

4.6.1 Constraints associated with effective implementation of SFIP……………….............................68

Chapter FIVE

………………………………………………………….…… ...........................................……70

SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS…….……....…...…….……....…...........................70

5.1 Summary……………………………………………………………..……... …... …….……....… ........... …...70

5.2 Conclusion………………………………………………………… …...…....… ........... ……….…....72

5.3 Recommendations……………………………………………………….….……....… ........... …....73

5.4 Suggestions for Further Study……………………………………………....……....… ........... …..74

5.5 Contribution to Knowledge……………………………………………….….

…...

….… ...........

….75

REFERENCES………………………………………………………… …...............… ........... ………........…...76

APPENDIX I………………………………………………………………..…..............................................…....86

APPENDIX II…………………………………………………………………..................................... ..........…..94

Thesis Abstract

ABSTRACT

This study was on Impact of Kogi Agricultural Development Project Survival Farming Intervention Programme on Cassava Production in Adavi, Okehi and Okene Local Government Areas of Kogi State and it also determine the factors that influence participation in SFIP. A multi-stage sampling technique was used to select respondents for the study. A total of one hundred and eighty (180) respondents comprising of ninety (90) participants and ninety (90) non-participants were interviewed with the aid of structured questionnaire which was also administered on ten (10) officials of SFIP to obtained vital information. Analytical tools used were both descriptive (frequency distribution tables, percentages and mean) and inferential statistics (logit regression and chow-test statistical tool). Attitudinal measuring scale such as likert-scale was also used. The results of the analysis obtained shows that majority of the respondents, 66% of the participants, 65% of the non-participants and 70% of the officials were within the age range of 36 - 55 years. Almost all the respondents are married with just few divorced and widowed. More also, about 12.2% of the participants and 47.8% of the nonparticipants had no formal education, while 76.6%, 52.2% and 60% of the participants, non-participants and the officials, respectively attended primary and secondary schools with only 7.8% of the participants and 40% of the officials who attended tertiary institutions. Based on the empirical evidence emanating from this study, planting material, access to credit, extension contact and training components of SFIP ranked 1st , 2 nd and 3rd respectively, among the highly aware and most used by the participants. Logit regression analysis showed R2 of 0.67969 meaning that about 68% of the variation in the participation of SFIP are been explained by the independent variables in the model. Age (X1), Marital status (X2), Labour (X4), Education (X5), Household (X7), Awareness (X10), Extension contact (X12), Cooperative (X13) and Planting material (X14) had positive coefficients and direct relationship with participation in SFIP implying that one unit increase in their variable coefficient will result to an increase in level of participation. Chow test F-calculated for output, yield, income and level of living were 16.31, 16.65, 21.06 and 28.01 respectively, while that of F-tabulated value for 9 degree of freedom with sample size of 180 was 1.83 at 5% level of probability, hence there was significant impact of SFIP on cassava production output, yield, income and level of living of the participants in the study area. All the null hypotheses were rejected while the alternative hypotheses were accepted. Major constraints identified by the participants were poor road network (67.8%) and poor market for products (40.0%) while majority (90.0%) of the officials attested to poor extension to farmers‟ ratio as a major constraint to effective implementation of SFIP in the study area. In overall, there was significant impact of SFIP on cassava production in the study area, hence it is recommended that the programme scaled-up and replicated in other LGAs and States in the country including FCT, Abuja.

Thesis Overview

INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to the Study Nigeria has substantial economic potential in its‟ agricultural sector. However, despite the importance of agriculture in terms of employment creation, its potential for contributing to economic growth is far from being fully exploited (USAID, 2005). The agricultural sector has been the mainstay of Nigeria‟s economy employing 70% of the active labour force and contributes significantly to the country‟s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and foreign earnings. In 1960, 1970, and 1980, it contributed 55.2%, 40.7% and 18% to GDP respectively, while its contribution to GDP in 1996, 1997, and 1999 stood at 39.0%, 39.4% and 40.4% respectively (NPC and UNDP, 1999). In 2010 agricultural contribution to GDP stood at 30.0%, while currently as at first quarter of 2012, it is contributing 34.4% to the GDP (NBS, 2012). However, there have been recorded decline in agricultural contribution to the national economic growth for over three decades now since emergence of the oil sector. This decline could be associated with the gross neglect of the agricultural sector and over dependence on the oil sector (Ugwu and Kanu, 2012).

The agricultural sector had been constrained with factors such as poor rural infrastructure, poor fertilizer distributions and high cost of farm inputs that could have enhance its production capacity and contribution to the national economy. The oil-boom era had lead to importation of food items in massive scale at the expense of locally produced ones because the rural farmers do not have the technological resources to compete in international market. This discourages the farmers from producing much because they no longer realized the needed profit from their effort (Ogunwole, 2004). The goal of increasing food production and reducing food import has elicited many programmes and policies at the various levels of government (Kudi et al., 2008). In order to revamp the agricultural sector, the Federal Government of Nigeria had embarked on and implemented several agricultural policies and programmes some of which are defunct or abandoned, and some restructured, while others are still in place. Presidential initiatives on cassava production and a number of new programme interventionsare currently implemented to increase area of cassava production, processing and marketing across the country.

Cassava is one of the most widely cultivated crops in the country. It is generally cultivated on small-holdings in association with crops such as maize, groundnut, cowpea, plantation (such as coffee, coconut and oil palm), vegetables and cocoyam depending on the agro-ecological zone and relies on residual soil nutrients when intercropped with maize which has been fertilized or as following crop in rotation with legumes (IITA, 2004; Chukwuji, 2008). Cassava is grown mainly on impoverished soils with no soil amendments such as fertilizers. Continuous cropping of cassava particularly the high yielding varieties without adequate maintenance of soil fertility could lead to soil and environmental degradation (IITA, 2004). Nigeria is the largest producer of cassava in the World. Its production is currently put at about thirty-four (34) million metric tonnes a year (FAO, 2002).

Nigeria‟s cassava production was targeted at forty (40) million tonnes in 2005 and sixty (60) million tonnes by 2020 (IITA, 2002). The presidential Initiative on Cassava Production and Export has increased the awareness amongst Nigerians of the industrial crop, popularly referred to as the „new black gold‟. According to Nweke et al. (2002)cassava performs five main roles namely: famine reserve crop, rural food staple, cash crop, industrial raw material and earning of foreign exchange. Uses of cassava products are enormous. Virtually, the whole plant from the leaves, stem and the roots has one use or the other. Daneji (2011) posited that, cassava is one of the most staple food crops in many households in Nigeria. The fresh peeled cassava roots are eaten raw, boiled or roasted. They can also be boiled and pounded to obtain "pounded fufu". This is most popular in the Eastern part of Nigeria. The processed cassava, either in the form of flour, wet pulp or “garri” is cooked or eaten in three main food forms: "fufu", "eba" and "chickwangue" (Adebile, 2012). Cassava leaves are rich in protein, calcium, iron and vitamins, comparing favourably with other green vegetables generally regarded as good protein sources. Cassava can be processed into several other products like chips, flour, pellets, adhesives, alcohol, starch, etc which are raw materials in livestock feed, alcohol/ethanol, textiles, confectionery, wood, food and soft drink industries (Iheke, 2008).

In a similar vein, Adebayo (2009) stated that processing the bulky, perishable crop is an obstacle to its full commercialization in sub-Saharan Africa. To motivate farmers, especially women who are the main processors of food in the village, to grow and process their cassava, we need to provide them with labour-saving implements such as graters, peelers, and crushers. There is also need to link them to markets. Cassava roots are bulky and with about 70.0% moisture content, are very perishable. It is therefore, expensive to transport cassava especially along poor access roads.

Therefore, a welldeveloped market access infrastructure is crucial for cassava marketing (Adeniji et al., 2006). However, focus should not be on the exportation of cassava but to develop the enormous local and regional markets for cassava that exist in the country, West African sub-region and Africa as a whole rather than start exporting the industrial raw material to Europe. According to Food and Agriculture Organization Statistics (2008) Nigeria‟s cassava export in 2005, was 2,100 tonnes compared to the leading exporter, Thailand, with 4,384,350 tonnes. The performance evaluation of marketing component of cassava initiative include, establishment of cassava processing centers in each Local Government Area(LGA) of the cassava producing States (Yisa, 2009).

In this regard, rural people are encouraged to add value to cassava products by processing it for industrial application and human consumption. Processing of cassava into various shelfstable and semi-stable products is a widespread activity in Nigeria carried out by traditional cassava processors and small-scale commercial processing units (Henk et al., 2007).

1.2 STATEMENT PROBLEMS

Nigeria has a huge agricultural resource endowment and yet the population is facing hunger and poverty. The agricultural sector is facing the problem of sustaining food production to meet up the need of increasing population in the country (Okolo, 2004; Ironkwe, 2005). Various governments in Nigeria have consistently declared policies aiming at self-sufficiency in food. The means toward achieving this objective has always been an expansion in cultivated area and improvement on the yield. Cassava is one of the major staple crops grown in Kogi State particularly in the study area. Government intervention programmes and policies, and the efforts of NonGovernmental Organizations (NGOs) in support of production, processing and marketing of cassava date back to the 1970s (Adeniji et al., 2006).

Some of the Government agricultural intervention programmes and policies aimed at increasing agricultural production especially cassava production include the Farm Settlement Scheme, National Accelerated Food Production Programme (NAFPP), Agricultural Development Projects (ADPs), River Basin Development Authorities (RBDAs), National Seed Service (NSS), National Centre for Agricultural Mechanization (NCAM), Agricultural and Rural Management Training Institute (ARMTI) and Agricultural Credit Guarantee Scheme Fund (ACGSF). Others were the Nigerian Agricultural Cooperative and Rural Development Bank (NACRDB), Agricultural Banks, Operation Feed the Nation (OFN), Green Revolution (GR), Directorate of Foods, Roads and Rural Infrastructure (DFFRI), Nigerian Agricultural Insurance Company (NAIC), National Agricultural Land Development Authority (NALDA) and Specialized Universities for Agriculture.

Agricultural Development Projects (ADPs) is an integrated approach which came into being as a result of the failure of special crop programmes to achieve rural development and food security objectives of government in Nigeria. As intervention strategies, these programmes have been designed to increase productivity in cassava sub-sector, as well as enhancing farmers‟ income from agriculture (Yisa, 2009). The NGOs efforts include Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development Project (SARDP), Rural Poverty Eradication Project (RPEP), Cassava Enterprise Development Project (CEDP) and others. All these programmes and policies due to one reason or the other have failed to meet the objective of self-sufficiency in food production.

A number of new initiatives are also currently being implemented to increase area of cultivation, yields, processing and marketing of cassava products in the country. These include the presidential initiatives on cassava production, the National Special Programme for Food Security (NSPFS), Root and Tuber Expansion Programme (RTEP) and Rural Banking Scheme (Ugwu and Kanu, 2012). The Root and Tuber Expansion Programme (RTEP) was formulated between 1995 and 1997 to consolidate the gains made under the Cassava Multiplication Project (CMP) of ADP in order to enhance national food self-sufficiency and improve rural household food security and income of poor farmers within the southern and middle belt States of the country.

1.3 OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

The broad objective of this study was to assess the Impact of Kogi Agricultural Development Project Survival Farming Intervention Programme on Cassava Production in Adavi, Okehi and Okene Local Government Areas of Kogi State. The specific objectives are to; i. describe the socio-economic characteristics of the programme participants and nonparticipants in the study area; ii. assess the level of awareness of the survival farming intervention programme components by the respondents in the study area; iii. determine the factors influencing participation of respondents in survival farming intervention programme on cassava production in the study area; iv. assess the impact of the survival farming intervention programme on cassava production of the participants and non-participants in the study area; v. assess the impact of the survival farming intervention programme on income and level of living of the participants and non-participants in the study area, and vi. identify the constraints associated with effective implementation of survival farming intervention programme in the study area.

1.4 JUSTIFICATION OF THE STUDY

It is important to note that a lot of work has been done on cassava as a crop in terms of its production, processing and packaging but there have been great variation in the scope of coverage (Adeniji et al., 2006; Adebayo, 2009; Yisa, 2009 and Chikezie et al., 2012). This study assessed the impact of survival farming intervention programme which is involve in production, processing and packaging of cassava produce. It is hoped to provide relevant information about SFIP that will be of benefit to both small and medium scale processing firms of cassava products. The findings are also expected to be useful to agricultural project/programme planners and implementers, donor agencies, project/programme supervising agencies, the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Mineral Resources (FMAMR), researchers and beneficiary of a project/programme in term of policy formulation and design of programme that better the life of rural people

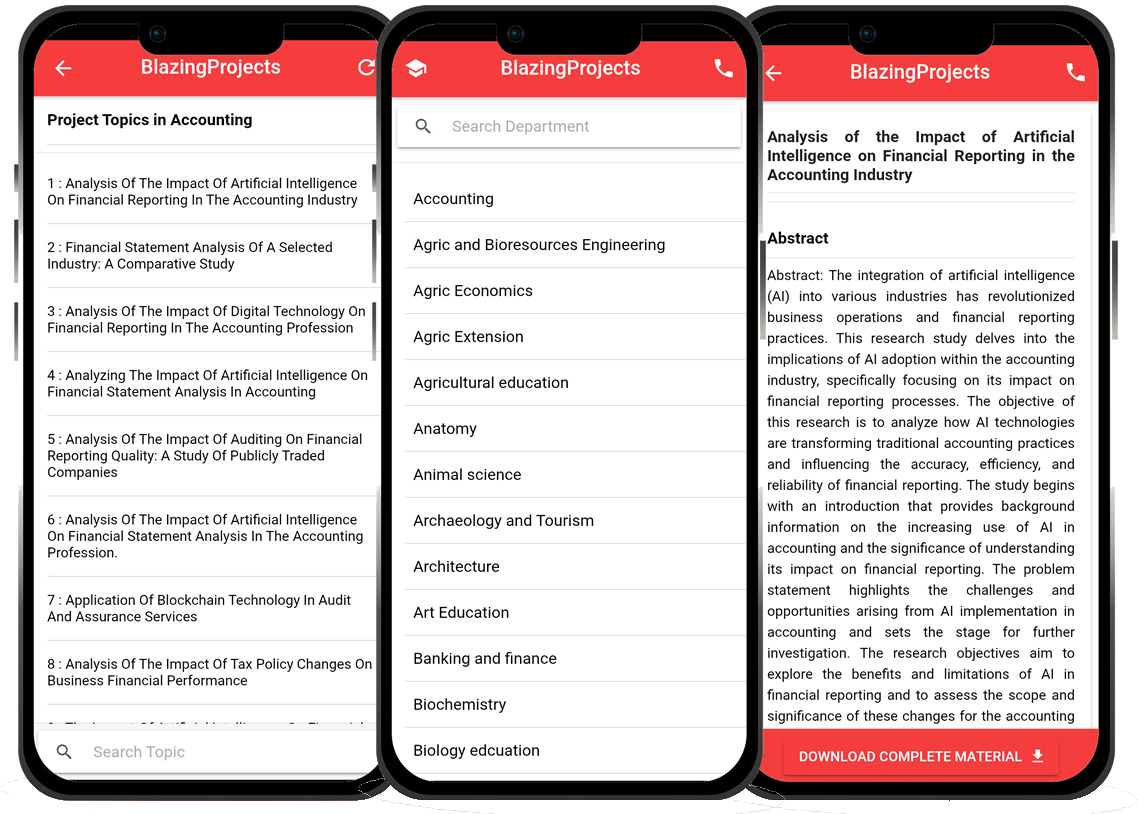

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Research Thesis

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Thesis-to-Journal Publication

🎓 Undergraduate/Postgraduate Thesis

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Assessing the Economic Viability of Precision Agriculture Technologies in Enhancing ...

The project titled "Assessing the Economic Viability of Precision Agriculture Technologies in Enhancing Crop Yield and Profitability" aims to investig...

Analyzing the Economic Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity...

The research project titled "Analyzing the Economic Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity" aims to investigate the intricate relations...

Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Adaptation Strate...

The project titled "Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Adaptation Strategies in [Specific Region]" aims to investigate...

Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study ...

The project titled "Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity: A Case Study of Smallholder Farmers in Nigeria" aims to inv...

Assessing the Economic Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in ...

The research project titled "Assessing the Economic Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Selected Region" aims to investigat...

Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Devel...

The research project titled "Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Developing Country" aims to examine the si...

Analysis of the impact of climate change on agricultural productivity and food secur...

The research project titled "Analysis of the impact of climate change on agricultural productivity and food security in a developing country" aims to ...

Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Speci...

The research project titled "Analysis of the Impact of Climate Change on Crop Yields and Farmer Income in a Specific Region" aims to investigate the e...

Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity and Household In...

The project titled "Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Agricultural Productivity and Household Income in Rural Communities" aims to investigate...