Evaluation of the nomadic primary school health education curriculum in adamawa state of nigeria

Table Of Contents

Chapter ONE

1.1 Introduction1.2 Background of study

1.3 Problem Statement

1.4 Objective of study

1.5 Limitation of study

1.6 Scope of study

1.7 Significance of study

1.8 Structure of the research

1.9 Definition of terms

Chapter TWO

2.1 Overview of Health Education Curriculum2.2 Historical Development of Health Education Curriculum

2.3 Theoretical Frameworks in Health Education Curriculum

2.4 Components of Health Education Curriculum

2.5 Models of Health Education Curriculum

2.6 Evaluation Frameworks for Health Education Curriculum

2.7 Challenges in Health Education Curriculum Implementation

2.8 Innovations in Health Education Curriculum

2.9 Best Practices in Health Education Curriculum

2.10 Global Perspectives on Health Education Curriculum

Chapter THREE

3.1 Research Design3.2 Sampling Methods

3.3 Data Collection Techniques

3.4 Data Analysis Procedures

3.5 Research Instrumentation

3.6 Ethical Considerations

3.7 Pilot Study

3.8 Data Validity and Reliability

Chapter FOUR

4.1 Overview of Findings4.2 Analysis of Health Education Curriculum in Nomadic Primary Schools

4.3 Stakeholder Perceptions on Health Education Curriculum

4.4 Comparison with National Curriculum Standards

4.5 Impact of Health Education Curriculum on Student Health

4.6 Recommendations for Curriculum Improvement

4.7 Implementation Strategies

4.8 Future Research Directions

Chapter FIVE

5.1 Summary of Findings5.2 Conclusions

5.3 Implications for Policy and Practice

5.4 Contributions to the Field

5.5 Recommendations for Further Research

5.6 Reflections on the Research Process

Thesis Abstract

ABSTRACT

This study evaluated the nomadic primary school Health Education curriculum in Adamawa State of Nigeria. Specifically, the study determined the extent of achievement of objectives of Health Education curriculum; teacher-pupil ratio and quality of human resources available for the implementation of the nomadic Health Education curriculum; adequacy of the Health Education content in addressing the nomads unique style of life; teaching methods used in nomadic Health Education programme; availability of Health Education instructional materials in nomadic primary schools; use of instructional materials in nomadic schools; learning experiences and activities of the pupils’ during instruction; assessment devices used by the nomadic primary school Health Education teachers; difficult areas in the content of Health Education curriculum as perceived by both the teachers’ and pupils’; and pupils demonstration of Health Education knowledge and skills. The study employed evaluative research design. Stufflebeam’s Context, Input, Process and Product (CIPP) Model was used. The population of the respondents includes 117 nomadic primary schools in Adamawa State Nigeria; 26,292 respondents comprising of 564 teachers, 12,848 pupils, 21 Education Secretaries, 11 Supervisors, and the 12,848 nomadic Parents of the pupils. A disproportionate stratified random sampling technique was used to draw respondents for the study. From the six zones, 585 respondents were used consisting of 120 teachers, 300 pupils, 150 nomadic parents, 9 education secretaries and 6 supervisors. Five instruments were used for the study Questionnaire with a four-point scale, Checklist, Observation Schedule, Interview Schedule and Focus Group Discussion Schedule (FGDS). Five experts validated the instruments. The instruments for the study were trial-tested on 60 teachers and 90 pupils. The data obtained from the trial tests were analysed and the Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient obtained were .95 on attainment of objectives, .98 on adequacy of Heath Education content, .99 on difficult content areas and .99 on pupils demonstrations of knowledge and skills as perceived by both the teachers and pupils. The overallr reliability coefficient was .99. The data collected on the 12 research questions were analysed qualitatively, and quantitatively using mean rating scores, standard deviation, frequency counts and percentages. The four hypotheses stated were tested at 0.05 level of significance using t-test for HO1, HO3 and HO4 and chi-square for HO2. The results of the study showed that The objectives of Health Education were achieved, Teacher-pupil ratio of 123 shows that there were enough teachers for the programme, teachers quality was inadequate, the content of Health Education programme in nomadic schools was adequate, Teachers appeared to use teacher-centered methods that are passive rather than pupil-centered methods that are activities based and participatory, Instructional resources were inadequate in the nomadic schools, Teachers use of instructional materials was generally low, Pupils were more or less passive during classes, Teachers use of assessment devices indicated more frequent use of oral device, Content areas of Health Education curriculum was adequate; Pupils demonstrated knowledge and skills of Health Education to a great extent, Attainment of Health Education objectives in settled and mobile schools indicated significant difference in favour of pupils in the mobile schools. The number of qualified teachers in the nomadic schools is independent of whether school is settled or mobile. There were no significant differences on the difficulty of the content areas and pupils’ use of Health Education knowledge and skills in settled and mobile schools. The educational implications of the findings were highlighted. The following recommendations among others were made Provision of adequate instructional materials; Teacher training and retraining

Thesis Overview

Background to study

The global consensus is that education is a process that helps the whole human being, physically, mentally morally, socially and technologically. This enables one to function in any environment in which one may find oneself. Education also performs a major role in equipping the individual with the skills and knowledge which would help to transform any economy. Thus, it is the greatest investment that any nation can make for the quick development of its economic, political, sociological and human resources. Believing that education is the cornerstone for national development, Nigeria has adapted education as the “principal instrument par excellence” for effective national development. Her philosophy of education is based on the integration of the individual into sound and effective citizenship with equal educational opportunities at all levels through the formal and non-formal school system. More importantly, the government of Nigeria believes that the provision of functional education is the primary means of upgrading the socioeconomic condition of the rural population. Such rural populations, particularly the nomadic pastoralists and the migrant fishermen are difficult to educate. This is reflected by their participation in existing formal and non-formal education programmes which are abysmally low; their literacy rate ranged between 0.2% and 2.0% (Tahir, 2003). The major constraints to their participation in formal and non-formal education as identified by the National Commission for Nomadic Education (1989) are as follows: (i) Their constant migration/movements in search of water and pasture in the case of the pastoralists; and fish in the case of migrant fishermen. (ii) The centrality of child labour in their production system, thus making it extremely difficult to allow their children to participate in formal schools. (iii) The irrelevance of the school curriculum which is not tailored to meet the needs of sedentary groups and thus ignores the educational needs of nomadic peoples; (iv) Their physical isolation, since they operate in largely inaccessible physical environments; (v) A land-tenure system that makes it difficult for the nomadic people to acquire land and settle in one place. In accord with the provisions of the 1979 constitution and the National Policy on Education which strongly urge government to provide equal educational opportunities to all Nigerians, the Federal Government launched the Nomadic Education on 4 th of November 1986. As a follow up to this, by decree No. 41 of December 1989, the Federal Government also established the National Commission for Nomadic Education (NCNE) charged with the responsibility of implementing the Nomadic Education Programme in the country. The broad goals of the programme as published by NCNE Blue Print are: 1. to provide the nomads with relevant and functional basic education; 2. to improve the survival skills of the nomads by providing them with knowledge and skills that will enable them raise their productivity and levels of income; and 3. to participate effectively in the nation’s socio-economic and political affairs. Since its inception, the National Commission for Nomadic Education (NCNE) has tried to evolve a number of distinct programmes, aimed at meeting the basic education needs of the migrant communities in Nigeria. They include the provision of: basic education to nomadic pastoralists and children of fishermen; academic support services; adult extension education linkage relationship for collaboration and partnership distance learning scheme project. Statement of the Problem The process of education, especially an educational delivery system for a marginalized group as the nomads is a dynamic one which needs to be constantly evaluated with a view to assessing its relevance, worth and importance in the rapidly changing situations of the modern world. Two decades of activities on the programme provide enough reasons for stocktaking on its performance. More-so, one of the major purposes of research is to find out “what is” as opposed to “what ought to be” and possibly to establish the cause of the discrepancy between the two with the view to remedying the situation. This research is designed to highlight the achievements and failures, strengths and weaknesses of nomadic education as perceived by the various stakeholders of the programme. It is also to assess the facilities provided to enhance the quality of nomadic education in Nigeria in terms of pupils’ assess, curriculum content, teachers’ competence, teaching processes, learning materials and learning environment in the nomadic schools. The following questions are therefore raised to guide the research. (1) To what extent has the programme fulfilled its primary function of providing relevant and functional basic education to the children of the nomads in Nigeria? (2) How adequate were the provisions of basic facilities to improve pupils’ access, curriculum content, teachers’ competence, teaching processes, learning materials and conducive school environment in the nomadic schools? (3) What is the extent of the programme’s overall contribution to, or impact on the nomadic population in general? (4) What are the major constraints facing the programme? Conceptual Framework This study is situated in one of the management-oriented evaluation model popularly known as the CIPP model. The CIPP model is a decision facilitation model which places more emphasis on data collection and storage to aid decision makers. The model was developed by Guba and Stufflebeam in 1970. As a strong proponent of decision oriented model, Daniel Stufflebeam views evaluation as the process of delineating, obtaining and providing useful information for judging decision alternatives (Stufflebeam, 1971). The CIPP has the ability to probe into four different but interrelated aspects of a programme. Its feedback mechanism allows for a focus on all the components of the programme and permits the placement of different emphasis on each of the components. CIPP is an acronym for four types of evaluation namely: Context Evaluation, Input Evaluation, Process Evaluation and Product Evaluation. Highlighting the various components of CIPP, Yoloye (1982) noted that context evaluation provides the rationale for determining the programme’s objectives. It seeks to isolate the problems or unmet needs in an educational setting. Input evaluation provides information regarding how to employ resources to achieve programme’s objectives. Process evaluation is required once the instructional programme is up and running. The purpose here is to identify any defects in the procedural design especially in the sense that planned element of the programme are not being implemented as they were originally conceived. Product evaluation attempts to measure and interpret the attainments yield by the programme not only as its conclusion but as often as possible during the programme itself. The main thesis of CIPP Model is decision-making. It answers four questions viz: 1. What procedures should be accomplished? 2. What procedures should be followed to accomplish the objectives? 3. Are the procedures working properly? 4. Are the objectives being achieved? Methodology This survey research covered six of the thirty-four states participating in nomadic education programme in Nigeria. Each of the six participating states was purposively selected to ensure participation from the six geo-political Zones of Nigeria. A total of 607 participants were randomly selected from the following stakeholders of nomadic education in the six states i. Officials of the National Commission for Nomadic Education ii. Officials of local education authorities iii. Nomadic community leaders and officials of nomadic organizations iv. Headmasters and Teachers in Nomadic schools. Instrumentation Four valid and reliable instruments developed by the researcher were used to collect data for the study. They are: 1. Attainment of Nomadic Education Goals Questionnaire (Cronbach coefficient alpha value = 0.89) 2. Nomadic Education Strategies and Facilities Scale. (Cronbach coefficient alpha value = 0.80) 3. Impact of Nomadic Education Questionnaire (Cronbach coefficient alpha value = 0.86) 4. Constraints of Nomadic Education Programme Questionnaire (Cronbach coefficient alpha value = 0.87) Data Collection and Analysis The instruments were administered directly to the subjects by the investigator and five other research assistants. Data analysis involves the use of frequency counts and means score. Results and Discussion Research Question 1 To what extent has the programme fulfilled its primary function of providing relevant and functional basic education the children of the nomads in Nigeria Table 1: Attainment of Short-Term Goals of Nomadic Education S/N Goals Very Low Low High Very High Mean 1 Read with comprehension those things that affect their occupational roles 14 (2.3) 51 (8.4) 467 (77.1) 74 (12.2) 2.99 2 Read and understand national papers to know what is happening around them 28 (4.6) 60 (9.9) 468 (77.2) 50 (8.3) 2.89 3 Write legible and meaningful letters to friends, veterinary and government officials on the need of the clans 29 (4.8) 67 (11.1) 464 (76.6) 46 (7.6) 2.87 4 Do simple calculation 26 (4.5) 4.7 (7.8) 80 (13.2) 452 (74.6) 3.58 5 Keep records relating to the number of their herds, distance covered on seasoned movement, etc. 19 (3.1) 47 (7.8) 477 (78.7) 63 (10.4) 2.96 6 Develop scientific outlook 38 (6.3) 58 (9.6) 456 (75.2) 54 (8.9) 2.87 7 Develop positive attitude and self-reliance to deal with their problems 23 (3.8) 58 (9.6) 476 (78.5) 49 (8.1) 2.91 8 Improve their relationship with immediate neighbours 28 (4.6) 59 (9.7) 472 (77.9) 47 (7.8) 2.89 9 Improve their relationship with farmers 31 (5.1) 52 (8.6) 61 (10.1) 462 (76.2) 3.57 10 Improve their relationship with government authorities or agents 45 (7.4) 50 (8.3) 55 (9.1) 456 (75.2) 3.52 Table 1 shows that majority of the respondents indicated that nomadic education has fulfilled its primary function to high extent. Majority, 467 (77.1%) indicated that the programme has assisted the beneficiaries to high extent on how to read with comprehension those things that affect their occupational roles. Majority also, 468 (77.2%) indicated that the programme enabled the beneficiaries to read and understand national papers and to know what is happening around them. More than seventy percent (70%) of the respondents also indicated high extent of fulfillment on other functions including ability of the recipients to do simple calculations, keeping of domestic records, developing scientific outlook and developing them with positive attitude to combat their immediate problems. The overall assessment is that the programme has fulfilled its primary function to a high extent among the beneficiaries. This is in agreement with the steady growth reported in the development of nomadic education in Nigeria as prepared by the Department of Programme Development and Extension, National Commission for nomadic Education, Kaduna Nigeria in 2001. As at March 2001, there were 1,574 nomadic primary schools located in all (36) States of the federation. Out of this number, 1102 were schools for nomadic pastoralists, while 472 were schools for migrant fishermen. The total pupil enrolment in these schools was203, 844 made up of 118, 905 males and 84, 939 female. The total number of teachers as at 2001 was 4,907. The report noted that since the inception of the programme in 1989 up till 2001, about 15,833 pupils have successfully graduated from the nomadic school system. This is made up of 10,290, boys and 5,543 girls, which represents 65% and 35% respectively. In the same vein, as at the 2001 academic session, there were 301 primary schools for migrant fishermen children in 26 local governments in the nine participating states in the riverine and coastal areas of Nigeria. There were 40,842 pupils in these schools with 22,352 boys and 18,489 girls and a total of 860 teachers. A steady increase was reported in 2008. The North East geo-political zone of Nigeria comprising Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno Gombe, Taraba and Yobe States had a total of 508 nomadic schools with 2,277 teachers and 67,950 pupils in enrolment (NCNC) Annual report 2008. So also the South East zone comprising of Abia, Anambra, Ebony, Enugu and Imo States had a total of 334 schools, 1 941 teachers and 46,567 enrolment of pupils in nomadic schools. Research Question Two How adequate were the provisions of basic facilities to improve access, curriculum content, teachers’ competence, teaching processes, learning materials and conducive school environment during the period covered in the study? Table 2: Mean rating Score on Nomadic Education Strategies/Facilities S/N Basic Strategies/Facilities Mean rating score over 10 1 The use of mobile school 4.90 2 The use of settlements centres 5.20 3 Involvement of nomads in the decision making process 5.49 4 Schooling is conventional 6.55 5 Nomadic education content is relevant to the lives of nomads 6.20 6 Nomadic curriculum are tailored to suit the cultural demands of nomads 5.47 7 The use of educational extension services 4.23 8 The use of radio/television to improve awareness of nomadic education 5.11 9 Nomadic teachers are specially trained for the programme 4.28 10 Provision for guidance counseling in nomadic schools 4.64 11 Provision of monitoring and evaluating nomadic programme periodically 4.25 12 Nomadic children walk short distances from home to school 4.31 13 Children possess relevant text-books 4.81 14 Children possess relevant writing materials 4.91 15 Nomadic schools are properly ventilated 5.62 16 Classrooms have ceilings 4.72 17 Classrooms are supplied with furniture 4.86 18 Classrooms have chalkboards 5.81 19 Classrooms have science equipment 4.55 20 Teachers improvise teaching aids 2.25 21 Teaching aids are supplied by the government 2.62 22 Teachers have opportunity for re-training such as short-term courses, seminars, workshops, sandwich programmes 2.57 23 Nomadic teachers receive regular allowances in addition to salaries 2.30 Table 2 shows that among twenty-three (23) strategies/facilities of nomadic education, only eight (8) were rated above average (5). They include: Schooling is conventional (6.55), Nomadic education content is relevant to the lives of nomads (6.20), Classrooms have chalkboards (5.81) and Nomadic schools are properly ventilated (5.62). The remaining fifteen (15) strategies were rated below average (5). These include: Teachers improvisation of teaching materials (2.25) and opportunity for teachers for re-training on the job (2.57). The result shows that most of the strategies/facilities are not meaningfully in place in nomadic education centres. This finding is also in agreement with the situation report on nomadic education conducted by the Department of Programme Development and extension National Commission for Nomadic Education Kaduna in 2001 which established inadequate teachers as well as inadequate supply of instructional materials such as text-books, exercise books, writing materials as well as classrooms, furniture etc. The situation and policy analysis reported that there were only 4,907 teachers for 1,574 nomadic schools i.e. a ratio of about 3 teachers per school. It these teachers lack of requisite teaching qualification prescribed by the government – e.g. the Nigerian Certificate in Education. Perhaps up to 60% of the teachers were unqualified. Research Question 3 What is the extent of the programme’s overall contribution to, or impact on the nomadic population in general? Table 3: Impact of Nomadic Education on General Population S/N Impact Statements Very Low Low High Very High Mean 1 Nomadic education has reduced intra-clan disputes in Nigeria 11 (5.4) 56 (27.6) 88 (43.3) 48 (23.6) 2.85 2 It has brought the awareness of the importance of western education and the development of positive attitude towards the nomads 11 (5.4) 35 (17.2) 105 (51.7) 52 (25.6) 2.98 3 It has increased literacy skills of nomads 16 (7.9) 35 (17.2) 100 (49.3) 52 (25.6) 2.93 4 It has improved the occupational roles of nomads 21 (10.3) 43 (21.2) 88 (43.3) 51 (25.1) 2.83 5 It has improved the economic enhancement of nomadic communities 21 (10.3) 54 (26.6) 85 (41.9) 43 (21.2) 2.74 6 It has improved the relationships with farmers 22 (10.8) 48 (23.6) 101 (49.8) 32 (15.8) 2.70 7 It has improved the relationships with government authorities 33 (16.3) 60 (29.6) 68 (33.5) 42 (20.7) 2.59 Majority of the respondents as shown in Table 4 indicated that nomadic education has a great impact on the nomadic communities. The followings were revealed from their responses among others: That nomadic education has reduced intra-clan disputes in Nigeria, It has also brought the awareness of the importance of western education and has favourably influenced the nomads to develop positive attitude to education. Furthermore, it has also increased literacy skills of nomads and improved their occupational roles. Research Question Four What are the major constraints facing the nomadic education programme? Table 4: Constraints facing the nomadic education programme S/N Constraints Very Low Low High Very High Mean 1 Inadequate funding 31 (5.4) 36 (6.3) 411 (72.0) 93 (16.3) 2.99 2 Inadequate infrastructural facilities 17 (3.0) 34 (6.0) 435 (76.2) 85 (14.9) 3.03 3 Inadequate instructional materials 17 (3.0) 372 (65.1) 106 (18.6) 76 (13.3) 2.42 4 Lack of adequate teaching staff 28 (4.9) 371 (65.0) 99 (17.3) 73 (12.8) 2.38 5 Indiscriminate transfer of teachers 35 (6.1) 63 (11.0) 92 (16.1) 381 (66.7) 3.43 6 Teachers’ truancy 55 (9.6) 61 (10.7) 386 (67.6) 69 (12.1) 2.82 7 Lack of incentives for the teachers and supervisors 25 (4.4) 49 (8.6) 406 (71.1) 91 (15.9) 2.99 8 Lack of adequate supervision 28 (4.9) 50 (8.8) 232 (40.6) 261 (45.7) 3.27 9 Lack of grazing reserves 30 (5.3) 48 (8.4) 238 (41.7) 255 (44.7) 3.26 10 Lack of water in school locations 25 (4.4) 179 (31.3) 86 (15.1) 281 (49.2) 3.09 11 Lack of health facilities 21 (3.7) 38 (6.7) 403 (70.6) 109 (19.1) 3.05 12 Lack of cooperation between Nomads and the host community 22 (3.9) 66 (11.6) 410 (71.8) 73 (12.8) 2.94 13 Lack of interest in schooling on the part of nomads 22 (3.9) 197 (34.5) 264 (46.2) 88 (15.4) 2.73 14 Wrong perception of nomadic education 19 (3.3) 363 (63.6) 124 (21.7) 65 (11.4) 2.41 15 Irrelevant curriculum 35 (6.1) 221 (38.7) 255 (44.7) 60 (10.5) 2.60 16 Inability to ensure full enrolment 27 (4.7) 47 (8.2) 417 (73.0) 80 (14.0) 2.96 17 Inability to ensure regular attendance 8 (1.4) 66 (11.6) 419 (73.4) 78 (13.7) 2.99 18 Lack of adequate accommodation for teachers 13 (2.3) 347 (60.8) 111 (19.4) 100 (17.5) 2.52 19 Inadequate accommodation for pupils 19 (3.3) 230 (40.3) 218 (38.2) 104 (18.2) 2.71 20 Security problems 59 (10.3) 359 (62.9) 55 (9.6) 98 (17.2) 2.34 The problems of the programme as identified by the stakeholders include: Inadequate funding, inadequate infrastructural facilities, indiscriminate transfer of teachers, teachers’ truancy, and lack of incentives for the teachers and supervisors Statutorily the Commission receives funds from two sources, the federal Ministry of Finance for its recurrent cost and the National Primary Education Commission (NPEC), for funding its school-based activities. This finding is also in agreement with the situation Report of 2001 which claimed that the main problem of nomadic education as it relates to funding ranges from inadequate funding to late release of funds even when such funds are approved. In case, there is discernible trend of inconsistency in the pattern of funding nomadic education, which is always at variance with the Commission’s plans and budgets. Because the Commission receives less than 30% of its budget request, it has been compelled to fund its field operations from its scanty resources in an attempt not to bring field operations to a half. Thus, the Commission is compelled to spread its lean resources thinly such that its impact is not properly felt and its objectives only tangentially realised. In addition, inadequate supervision and inspection of schools was report by the Commissions situation report of 2001. Regular supervision and inspection of schools is the responsibility of Local Government Education Authorities and State Primary Education Boards ?(SPEBs). Lack of adequate means of transportation has hampered the supervision of schools, hence the need to provide supervisors and inspectors with motorcycles and bicycles Implications and Recommendations Going by the policies of the Federal government of Nigeria and the constitutional requirements on education, the provision of educational facilities for all sons and daughters of this country is not a privilege but a right. The efforts of the Federal government towards the provision of education to its nomadic population are commendable and a very well deserved case of social justice. The stakeholders of the programme perceived the programme as a huge success in terms of providing relevant and functional basic education to the children of the nomads and positively impacting the nomadic communities in Nigeria. This is in agreement with the empirical findings of other researchers, Ahmed (1998), Tahir (1998), Abubakar (2007) and Abdul-Mumin (2007). In spite of the numerous problems facing the programme in the country, a lot of achievements have been recorded. A lot more will be achieved in the future if the government adequately fund the programme, supply adequate infrastructural facilities and train and employ adequate teaching staff. Other areas that need adequate attention relates to the issue of indiscriminate transfer of teachers, truancy of nomadic teachers, short supply of educational supervisors and adequate facilities for healthy environment. References Abdul, M. (2007): Pastoral Fulani and family life education in Nigeria: The case of southern Borno nomads. Journal of Nomadic Studies No. 5 Abubakar, T. (2007): Situational Analysis of Nomadic education in South Eastern Nigeria. Journal of Nomadic Studies No. 5. Ahmed A. (1998): Evaluation of Nomadic Education in North Eastern Nigeria. An unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ibadan. Federal Government of Nigeria (1989): National Commission for Nomadic Education Decree 41 of 1989. Federal Government of Nigeria (1989): Operational Guidelines on Nomadic Education. Kaduna: National Commission for Nomadic Education. Federal Government of Nigeria (2004): National Policy on Education. Federal Ministry of Information. Federal Government of Nigeria (1993): Situation and Policy Analysis of Basic Education in Nigeria: National Report. Lagos: Federal Government of Nigeria/UNICEF. Kerlinger F.N. (1973): Foundations of Behavioural Research. New York: Holt, Rinchait & Winston Tahir, G. (2003) Basic Education in Nigeria. Ibadan: Sterling-Horden Publishers. Tahir. G. (1998) Nomadic Education in Nigeria: Issues, Problems and Prospects. Journal of Nomadic Studies Vol. 1, 10-21. Yoloye E.A. (1982): Evaluation Innovation. Ibadan: University Press.

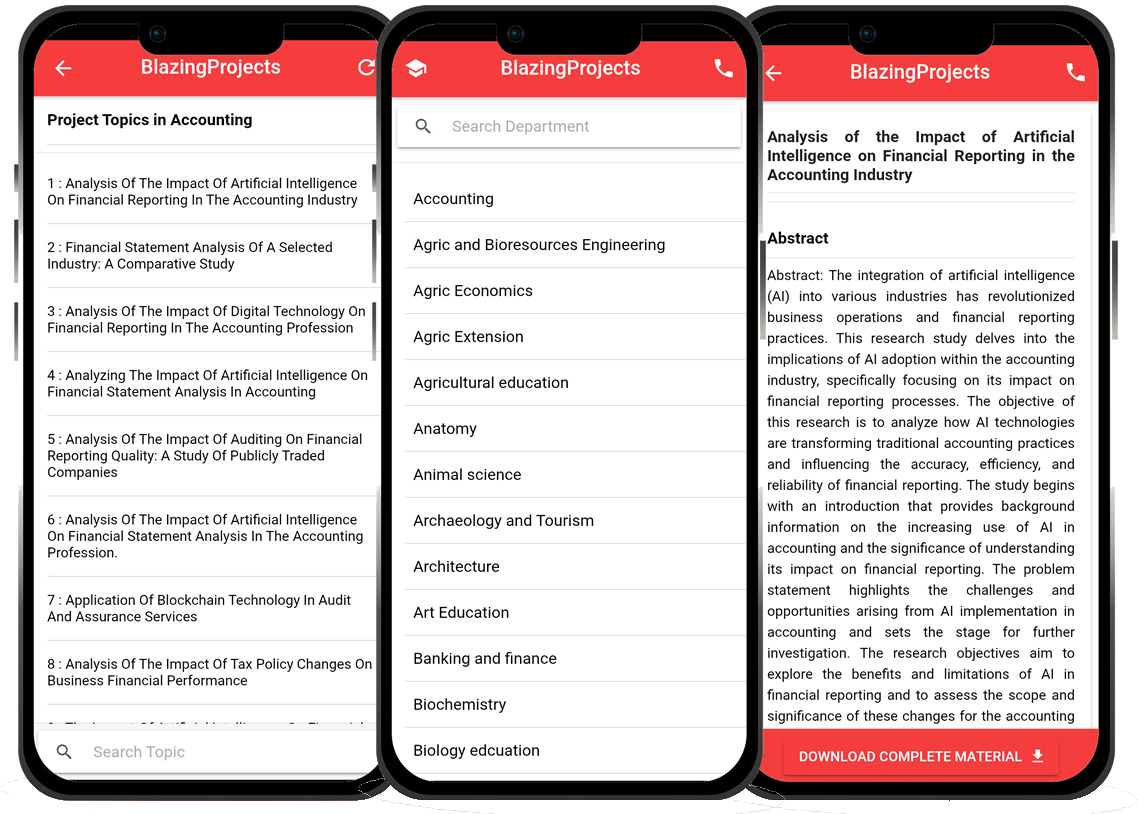

Blazingprojects Mobile App

📚 Over 50,000 Research Thesis

📱 100% Offline: No internet needed

📝 Over 98 Departments

🔍 Thesis-to-Journal Publication

🎓 Undergraduate/Postgraduate Thesis

📥 Instant Whatsapp/Email Delivery

Related Research

Analysis of the Impact of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) on Fina...

...

Analyzing the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Financial Reporting in the Accoun...

...

Analyzing the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Financial Statement Analysis in A...

...

Analyzing the Impact of Blockchain Technology on Financial Reporting in the Accounti...

...

Analysis of the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Financial Reporting in Accounti...

...

Exploring the impact of digital transformation on financial reporting in the account...

...

An analysis of the impact of digital technologies on financial reporting practices i...

...

Analysis of Financial Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises in the Retail Sect...

...

Application of Artificial Intelligence in Fraud Detection in Accounting...

...